CRISPR vs TALEN vs ZFN: A 2025 Efficiency Comparison for Research and Therapeutic Applications

This article provides a comprehensive, up-to-date comparison of the three primary genome editing technologies—CRISPR, TALEN, and ZFN—tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

CRISPR vs TALEN vs ZFN: A 2025 Efficiency Comparison for Research and Therapeutic Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive, up-to-date comparison of the three primary genome editing technologies—CRISPR, TALEN, and ZFN—tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational mechanisms of each system, explores their current methodological applications in both basic research and clinical trials, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and offers a validated, head-to-head comparison of their editing efficiency, precision, and practicality. The analysis incorporates the latest 2025 clinical data, market trends, and technological advancements to serve as a decision-making guide for selecting the optimal gene-editing tool for specific projects.

The Genome Editing Trinity: Understanding the Core Mechanisms of CRISPR, TALEN, and ZFN

The advent of gene-editing technologies has revolutionized biomedical research and therapeutic development, enabling precise modifications to genomic DNA. Among these tools, CRISPR-Cas9 has emerged as the most widely used platform due to its simplicity, efficiency, and versatility [1]. This guide provides an objective comparison of CRISPR-Cas9 against two predecessor technologies: Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs) and Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs). The analysis is framed within the broader thesis of understanding their relative efficiencies, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies. While CRISPR-Cas9 originates from a bacterial adaptive immune system that uses RNA guides for target recognition, TALENs and ZFNs rely on engineered protein domains for DNA binding [1] [2]. This fundamental difference in DNA recognition mechanism underpins many of their comparative advantages and limitations in research and therapeutic contexts.

Technology Comparison: Mechanisms and Characteristics

The core function of CRISPR-Cas9, TALENs, and ZFNs is to create double-strand breaks (DSBs) at specific genomic locations. These breaks are then repaired by the cell's endogenous DNA repair mechanisms, primarily non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR), leading to gene knockouts or precise edits, respectively [1]. However, each technology achieves this goal through distinct molecular architectures.

The table below provides a systematic comparison of the key technical characteristics of these three genome-editing platforms:

| Feature | CRISPR-Cas9 | TALEN | ZFN |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Recognition Mechanism | guide RNA (gRNA) [2] | TALE protein [2] | Zinc finger protein [2] |

| Nuclease Component | Cas9 protein [2] | FokI dimer [2] | FokI dimer [2] |

| Target Specificity | High (with gRNA design) [2] | Very High [2] | Very High [2] |

| Off-Target Effects | Higher than TALEN/ZFN [2] | Lower than CRISPR-Cas9 [2] | Lower than CRISPR-Cas9 [2] |

| Ease of Design | Very simple (within a week) [1] | Complex (~1 month) [1] | Complex (~1 month for ZFNs [1], but design is technically demanding [2]) |

| Relative Cost | Low [1] | Medium [1] | High [1] |

| Key Advantage | Simplicity, versatility, low cost [2] | High precision, lower off-target activity [2] | High specificity, smaller size advantageous for viral delivery [3] [2] |

| Key Limitation | Off-target effects [2] | Labor-intensive to construct [2] | Technically demanding design, context-dependent off-target activity [1] [2] |

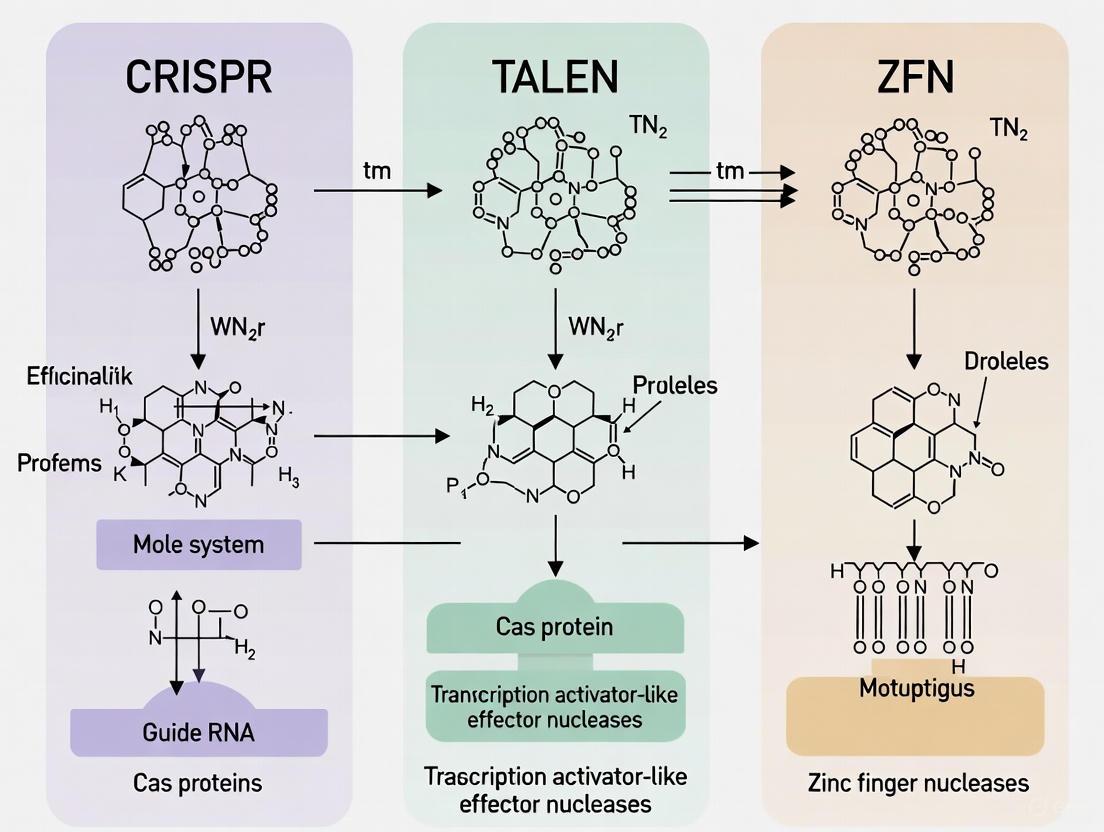

Diagram 1: Comparative mechanisms of CRISPR-Cas9, TALEN, and ZFN systems. All systems ultimately create a double-strand break in DNA, but differ fundamentally in their targeting components: CRISPR-Cas9 uses RNA-guided targeting, while TALEN and ZFN use protein-guided targeting requiring dimerization.

Experimental Data & Efficiency Comparison

Editing Efficiency in Human Cells

A 2025 study demonstrated a streamlined approach for ZFN delivery, showing that T2A-coupled ZF-ND1 monomers co-expressed from a single cassette efficiently cleaved target DNA sequences. The genome editing efficiency was equivalent to using two separate ZF-ND1 monomers, while reducing the total transfected plasmid DNA by half. This T2A-coupled system achieved efficient editing in both HEK293T and Jurkat cell lines [3].

Gene Insertion Efficiency in Hematopoietic Stem Cells

Recent research on non-viral gene insertion provides direct comparative data. A 2025 Nature Communications study reported that combining TALEN with circular single-stranded DNA (CssDNA) donor templates achieved high gene insertion frequency in Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cells (HSPCs) [4]. When compared to linear ssDNA (LssDNA), CssDNA demonstrated:

- 3- to 5-fold higher gene knock-in efficiency than LssDNA, with efficiencies surpassing 40% [4]

- Higher knock-in to knock-out ratio (1.30 for CssDNA vs. 0.11 for LssDNA with a 0.6 kb template) [4]

- Improved cell viability and reduced impact on differentiation capacity [4]

Notably, compared to AAV6-edited HSPCs, CssDNA-edited HSPCs exhibited a greater capacity to engraft and maintain gene edits in murine models, suggesting potential functional advantages for therapeutic applications [4].

Advancements in CRISPR-Cas9 Specificity and Delivery

Significant progress has been made in addressing CRISPR-Cas9 limitations. Deep learning models like CRISPR_HNN, which integrate MSC, MHSA, and BiGRU architectures, have demonstrated enhanced accuracy in predicting sgRNA on-target activity by better capturing local dynamic features and global long-distance dependencies [5].

For base editors (CRISPR-derived systems that enable precise nucleotide changes without double-strand breaks), novel deep learning models trained simultaneously on multiple experimental datasets have significantly improved prediction accuracy. These "dataset-aware" models, termed CRISPRon-ABE and CRISPRon-CBE, allow researchers to tailor predictions to specific base editors and experimental conditions, addressing a longstanding challenge in precise editing design [6].

Furthermore, AI-designed CRISPR systems are emerging. One 2025 study reported the development of OpenCRISPR-1, a gene editor designed with large language models that exhibits comparable or improved activity and specificity relative to SpCas9, despite being 400 mutations away in sequence [7].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This protocol describes an efficient method for implementing ZFN editing using a single expression cassette.

- Plasmid Design: Construct a single plasmid coding for ZF(L)-ND1RRR and ZF(R)-ND1DDD linked using a T2A peptide. The T2A peptide enables co-expression of both monomers from a single cassette via ribosomal skipping.

- Cell Transfection: Transfect the plasmid into target cells (HEK293T or Jurkat). For a 6-well plate format, use 1-2 µg of total plasmid DNA, which is approximately half the amount required when using two separate plasmids for individual monomers.

- Incubation and Analysis: Incubate transfected cells for 72 hours to allow for gene editing to occur.

- Editing Efficiency Assessment: Extract genomic DNA and analyze editing efficiency using the T7EI assay or next-generation sequencing to quantify indel frequencies.

- Critical Note: The T2A peptide is preferred over P2A for ZFN systems, as the cleaved P2A peptide (adding 21 amino acids to ND1RRR) significantly reduces editing efficiency, while the T2A peptide (adding 20 amino acids) does not impair ND1 nuclease dimerization.

This protocol describes an efficient non-viral gene insertion method for hematopoietic stem cells.

- HSPC Culture: Thaw and expand HSPCs for 2 days in appropriate cytokine-enriched media.

- TALEN mRNA Transfection: On day 2, electroporate cells with 3 mRNA molecules encoding:

- TALEN targeting the desired locus (e.g., TALENB2M for B2M locus)

- HDR-Enh01 mRNA to enhance homology-directed repair

- Via-Enh01 mRNA to improve cell viability after editing

- CssDNA Template Delivery: On day 3, perform a second transfection with the circular single-stranded DNA donor template (0.6 kb to 2.2 kb in length) containing homology arms specific to the target locus.

- Culture and Analysis: Continue culture for 1-14 days depending on the readout. Analyze editing efficiency by flow cytometry for surface reporter expression (for disruptive insertion) or molecular assays for precise integration.

- Functional Validation: For therapeutic applications, perform colony-forming unit (CFU) assays to assess differentiation capacity and engraft edited HSPCs in immunodeficient NCG mice to evaluate long-term repopulation potential and edit persistence.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for TALEN-mediated gene insertion in HSPCs using CssDNA donor templates. This multi-day process involves sequential delivery of TALEN mRNA followed by CssDNA template, with comprehensive functional validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key reagents and their applications in genome editing research:

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Circular ssDNA (CssDNA) | Non-viral donor template for gene insertion; reduces cytotoxicity and improves HDR efficiency compared to linear DNA [4]. | Enzymatically synthesized; 0.6-2.2 kb templates; 3-5x more efficient than linear ssDNA in HSPCs [4]. |

| TALEN mRNAs | Engineered nucleases for creating targeted double-strand breaks; used with DNA donor templates for precise gene insertion [4]. | Specific TALEN (e.g., TALENB2M for B2M locus); electroporated into cells as mRNA for transient expression [4]. |

| HDR-Enh01 mRNA | Enhances homology-directed repair efficiency when co-delivered with nuclease, increasing precise gene insertion rates [4]. | Electroporated alongside TALEN mRNA; improves knock-in efficiency in primary cells [4]. |

| Via-Enh01 mRNA | Improves cell viability after electroporation and editing process, particularly important for sensitive primary cells [4]. | Co-delivered with TALEN and HDR-Enh01 mRNAs; critical for maintaining HSPC fitness [4]. |

| AAV Vectors | Viral delivery system for DNA donor templates; high efficiency but concerns regarding genotoxicity and immunogenicity [4]. | AAV6 common for HSPCs; CssDNA shows superior engraftment capacity in comparative studies [4]. |

| T2A-Coupled ZFN Plasmids | Single-plasmid system for ZFN delivery; reduces DNA load and simplifies transfection [3]. | Enables co-expression of both ZFN monomers from single cassette; reduces total plasmid DNA by half [3]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Guides | Synthetic guide RNAs for directing Cas9 to specific genomic targets; easily programmable for new targets [2]. | Commercial libraries available; deep learning models (e.g., CRISPR_HNN) improve on-target activity prediction [5]. |

| Base Editor Systems | CRISPR-derived editors that enable precise nucleotide changes without double-strand breaks; reduce indel formation [6]. | ABE (Adenine Base Editor) and CBE (Cytosine Base Editor); prediction tools (CRISPRon-ABE/CBE) improve gRNA design [6]. |

The comparative analysis of CRISPR-Cas9, TALEN, and ZFN technologies reveals a nuanced landscape where each system offers distinct advantages depending on the research or therapeutic context. CRISPR-Cas9 remains the most accessible and versatile platform, with ongoing advancements in specificity prediction and AI-assisted editor design addressing its limitations. TALEN systems demonstrate superior precision in challenging genomic contexts and, when combined with novel delivery methods like CssDNA, achieve remarkable efficiency in therapeutically relevant primary cells. ZFNs, while historically complex to design, benefit from compact architecture advantageous for viral delivery and continued optimization in expression systems. The selection of an appropriate editing technology ultimately depends on the specific application requirements, including target specificity, delivery constraints, and desired edit type. As all three platforms continue to evolve, they collectively expand the frontiers of precise genome engineering for both basic research and clinical applications.

Gene editing technologies have revolutionized biological research and therapeutic development, enabling precise modifications to genomic DNA. Among the leading platforms, Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs) represent a sophisticated protein-based system that balances high specificity with versatile targeting capabilities [1]. This guide provides an objective comparison of TALEN performance against other major editing tools—CRISPR-Cas9 and Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs)—framed within current efficiency research landscapes.

The global gene editing market, projected to grow from $6 billion in 2024 to $22 billion by 2033, reflects the escalating adoption and commercial significance of these technologies across biopharmaceutical, agricultural, and research sectors [8]. Within this expanding ecosystem, TALENs maintain a distinct position despite the widespread popularity of CRISPR systems, particularly for applications demanding exceptional precision and reduced off-target effects [9].

This article examines TALENs through multiple dimensions: molecular mechanism, quantitative performance metrics, experimental applications, and practical implementation considerations. By synthesizing direct comparative studies and recent technological advancements, we aim to provide researchers with evidence-based guidance for platform selection in specific experimental or therapeutic contexts.

Molecular Mechanism of TALENs

TALENs function as engineered fusion proteins that combine a customizable DNA-binding domain with a non-specific nuclease domain. The DNA-binding component originates from transcription activator-like effectors (TALEs), proteins naturally produced by the plant pathogen Xanthomonas to manipulate host gene expression [1]. These proteins utilize a remarkable modular recognition system where each TALE repeat domain, comprising 33-35 amino acids, binds to a single specific nucleotide [9] [1].

The nucleotide specificity is determined by two key amino acid residues at positions 12 and 13 within each repeat, known as Repeat Variable Diresidues (RVDs). The RVD code enables predictable DNA recognition: NN recognizes adenine (A), NI recognizes adenine (A), NG recognizes thymine (T), HD recognizes cytosine (C), and NH or NK recognizes guanine (G) [1]. This modular architecture allows researchers to engineer TALE arrays that bind virtually any user-defined DNA sequence by assembling the appropriate repeat domains in the required order.

For genome editing applications, the TALE DNA-binding domain is fused to the catalytic domain of the FokI restriction endonuclease, which introduces double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA [10] [1]. Unlike CRISPR-Cas9 which functions as a single protein-RNA complex, TALENs operate as pairs—left and right monomers—that bind to opposite DNA strands with a spacer sequence between them. Dimerization of the FokI nuclease domains across this spacer region is required for enzymatic activation and subsequent DNA cleavage [1].

The following diagram illustrates the core architecture and mechanism of TALENs:

After TALEN-mediated DNA cleavage, cellular repair mechanisms are activated. The primary pathways include error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), which often results in insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt gene function, and homology-directed repair (HDR), which enables precise genetic modifications when a donor template is provided [10] [1]. The requirement for FokI dimerization contributes to TALEN specificity, as cleavage only occurs when both monomers correctly bind their target sequences in proper orientation and spacing.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Direct comparative studies provide valuable insights into the relative performance characteristics of TALENs, CRISPR-Cas9, and ZFNs. The following tables summarize key efficiency and specificity metrics across multiple parameters:

Table 1: Overall Performance Metrics Across Gene Editing Platforms

| Parameter | TALEN | CRISPR-Cas9 | ZFN |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targeting Precision | High specificity, minimal off-target effects [11] | Moderate to high, subject to off-target effects [10] | High specificity with proper design [12] |

| Design Complexity | Moderate (∼1 month) [1] | Very simple (within a week) [10] [1] | Complex (∼1 month) [1] |

| Relative Cost | Medium [1] | Low [10] [1] | High [10] [1] |

| Editing Efficiency | Variable (context-dependent), high in heterochromatin [11] | Generally high in euchromatin [10] | Variable (design-dependent) [3] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Limited | High (simultaneous multi-gene editing) [13] | Limited |

| PAM/PAM-like Requirement | No PAM, but must begin with T [1] | NGG PAM for SpCas9 [9] | No PAM, but specific spacer requirements |

| Delivery Efficiency | Challenging due to large protein size [9] [1] | High (compatible with various delivery systems) [10] | Moderate (smaller than TALENs) [3] |

Table 2: Experimental Efficiency Data from Comparative Studies

| Study Focus | TALEN Performance | CRISPR-Cas9 Performance | ZFN Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPV16 Gene Therapy Target (GUIDE-seq) | URR: 1 off-targetE6: 7 off-targetsE7: 36 off-targets | URR: 0 off-targetsE6: 0 off-targetsE7: 4 off-targets | URR: 287 off-targets | [12] |

| Heterochromatin Editing | Up to 5x more efficient than CRISPR-Cas9 [11] | Reduced efficiency in tightly-packed DNA [11] | Not specified | [11] |

| AAV Delivery Compatibility | Challenging (large coding sequence) [1] | Limited by Cas9 size [3] | Favorable (compact size) [3] | [3] [1] |

| Therapeutic Applications | Preferred for high-specificity edits [10] | Broad applications, though limited by off-target concerns [10] | Proven in clinical settings (e.g., HIV therapy) [10] | [10] |

Recent advances in TALEN engineering have addressed some limitations while enhancing strengths. The development of T2A-coupled monomer systems enables more efficient expression from single cassettes, potentially improving editing efficiency while reducing delivery payload requirements [3]. Additionally, optimization of TALE repeat domains has expanded targeting range while maintaining high specificity.

Experimental Applications and Protocols

TALEN-Specific Workflow

Implementing TALEN editing requires a methodical approach from design to validation. The following diagram outlines the core experimental workflow:

Key Methodology: GUIDE-Seq for Specificity Assessment

The genome-wide unbiased identification of double-stranded breaks enabled by sequencing (GUIDE-seq) provides a comprehensive method for assessing nuclease specificity across platforms [12]. This protocol has been adapted for comparative analysis of TALENs, ZFNs, and CRISPR-Cas9:

Oligonucleotide Tag Delivery: Transfect cells with TALEN encoding vectors alongside a blunt-ended, double-stranded GUIDE-seq oligonucleotide tag.

Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest cells 48-72 hours post-transfection and extract genomic DNA.

Tag Integration Enrichment: Capture tag-integrated genomic fragments through PCR amplification using tag-specific and genome-specific primers.

Library Preparation & Sequencing: Prepare sequencing libraries and perform high-throughput sequencing to identify tag integration sites.

Bioinformatic Analysis: Process sequencing data with customized algorithms to map double-strand break locations and frequency, comparing observed off-target sites with in silico predictions.

This methodology enabled direct comparison in the HPV16 study, revealing that "SpCas9 was more efficient and specific than ZFNs and TALENs" for certain targets, with TALENs demonstrating intermediate off-target profiles [12].

Heterochromatin Editing Assessment

Single-molecule imaging techniques have revealed TALEN's superior performance in densely packed DNA regions:

Fluorescent Tagging: Label TALEN and CRISPR-Cas9 components with distinct fluorophores.

Live-Cell Imaging: Monitor nuclease movement and binding kinetics in living mammalian cells using single-molecule fluorescence microscopy.

Binding Kinetics Analysis: Quantify time required for nucleases to locate and bind target sites in euchromatin versus heterochromatin regions.

Editing Efficiency Correlation: Measure actual editing efficiency at characterized genomic loci through sequencing analysis.

This approach demonstrated TALEN is "up to five times more efficient than CRISPR-Cas9 in parts of the genome, called heterochromatin, that are densely packed" [11].

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful TALEN experimentation requires specific reagents and systems. The following table outlines essential materials and their applications:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for TALEN Experiments

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| TALE Repeat Plasmids | Modular building blocks for custom DNA-binding domains | TALEN construct assembly |

| T2A-Peptide Vectors | Enables coordinated expression of TALEN pairs from single cassette [3] | Improved delivery efficiency |

| FokI Nuclease Domains | Provides dimerization-dependent cleavage activity | TALEN effector function |

| GUIDE-seq Oligonucleotides | Tags double-strand breaks for genome-wide specificity profiling [12] | Off-target assessment |

| T7 Endonuclease I | Detects heteroduplex mismatches in PCR-amplified target sites | Editing efficiency validation |

| AAV Delivery Vectors | Viral delivery of TALEN components; challenging due to size constraints [3] | In vivo applications |

| HEK293T Cell Line | Model system for TALEN validation and optimization | Efficiency testing |

TALEN technology represents a powerful option in the gene editing toolkit, particularly when project requirements prioritize high specificity, activity in heterochromatin regions, or applications where CRISPR off-target effects present unacceptable risks. While CRISPR systems excel in simplicity, multiplexing capacity, and broad accessibility, TALENs maintain distinct advantages in contexts demanding protein-based precision and proven regulatory acceptance pathways.

The choice between platforms should be guided by specific experimental goals, target genomic context, delivery constraints, and risk tolerance regarding off-target effects. As the gene editing field evolves, continued refinement of all major platforms—including enhanced Cas variants, improved TALEN delivery systems, and compact ZFN architectures—will further empower researchers to select optimal tools for their specific applications.

Zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs) represent the pioneering technology that opened the era of targeted genome editing. As the first programmable nucleases to demonstrate efficient gene editing in higher eukaryotes, ZFNs established the foundational concept of using engineered DNA-binding domains fused to non-specific nuclease domains to create targeted double-strand breaks in genomic DNA [14] [15]. These chimeric proteins are constructed by fusing a custom-designed zinc-finger protein (ZFP) DNA-binding domain to the cleavage domain of the FokI restriction enzyme [14]. The development of ZFNs marked a significant milestone in molecular biology, transitioning from random mutagenesis and inefficient homologous recombination to precise genome surgery with therapeutic potential. This technology proved that artificial enzymes could be engineered to manipulate virtually any gene in a diverse range of cell types and organisms, setting the stage for subsequent genome editing platforms [15].

Molecular Mechanism of ZFNs

Structural Architecture and DNA Recognition

The functional architecture of ZFNs consists of two primary components: a DNA-binding domain composed of zinc-finger proteins and a catalytic domain derived from the FokI endonuclease. Each zinc finger domain recognizes a specific 3-4 base pair DNA sequence through coordination by zinc ions and α-helical structures that interface with the DNA major groove [14] [15]. Engineered ZFN pairs typically incorporate arrays of three to six zinc fingers, enabling recognition of 9-18 base pair sequences per subunit [14]. For successful DNA cleavage, two ZFN subunits must bind to opposite DNA strands in a tail-to-tail orientation, with their recognition sites separated by a 5-7 base pair spacer sequence [14] [16]. This requirement for dimerization adds a critical layer of specificity, as the binding of two independent ZFNs in close proximity is necessary to initiate DNA cleavage.

DNA Cleavage Mechanism and Repair Pathways

Upon binding to their target sequences, the FokI cleavage domains dimerize and introduce a double-strand break (DSB) within the spacer region [14]. This DSB activates the cellular DNA damage response, engaging one of two major repair pathways. The non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway directly ligates the broken DNA ends in an error-prone manner, often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels) that can disrupt gene function [14] [15]. Alternatively, the homology-directed repair (HDR) pathway uses a homologous DNA template to precisely repair the break, enabling precise gene modifications when an exogenous donor template is provided [14]. The balance between these pathways varies by cell type and cell cycle stage, with NHEJ dominating in G1 phase and HDR being most active in S/G2 phases [14].

Figure 1: ZFN Mechanism of Action. ZFNs function through (1) sequence-specific DNA binding and FokI dimerization, (2) targeted double-strand break formation, and (3) engagement of cellular DNA repair pathways leading to either gene disruption or precise editing.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Editing Efficiencies Across Platforms

Direct comparison of genome editing platforms reveals distinct efficiency profiles. A 2021 study using genome-wide unbiased identification of double-stranded breaks enabled by sequencing (GUIDE-seq) to evaluate nucleases targeting human papillomavirus (HPV) genes provides quantitative insights into the performance characteristics of ZFNs compared to TALENs and CRISPR-Cas9 [17].

Table 1: Comparison of Editing Efficiencies Between Programmable Nucleases

| Nuclease Type | Target Gene | Editing Efficiency | Absolute HDR Frequency | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZFNs | CCR5 | High disruption efficiency | Up to 20% in human cells [15] | Compact size compatible with AAV delivery [16] |

| ZFNs | Rhodopsin | Demonstrated DSB induction | 17% HDR in retinoblast cells [18] | High specificity with extended target recognition [16] |

| TALENs | MSTN | Moderate efficiency | Lower than CRISPR in goat fibroblasts [19] | Lower cell toxicity than early ZFNs [15] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 | MSTN | Highest efficiency | Superior to TALENs in comparative study [19] | Simplified design and multiplexing capability [19] |

Specificity and Off-Target Profiles

A critical consideration for therapeutic applications is nuclease specificity. The GUIDE-seq analysis of HPV-targeted nucleases revealed substantial differences in off-target activities between platforms [17]. ZFNs targeting the HPV URR region generated 287-1,856 off-target events, with specificity correlating with the count of middle "G" nucleotides in zinc finger proteins [17]. In the same study, TALENs targeting the E7 gene produced 36 off-target events, while CRISPR-Cas9 targeting the same region generated only 4 off-target events [17]. This substantial difference in off-target activity highlights a significant challenge for ZFN technology. However, advanced ZFN architectures featuring obligate heterodimeric FokI domains have demonstrated substantial improvements in specificity by preventing homodimerization at off-target sites [14] [16].

Table 2: Off-Target Activity Comparison Across Nuclease Platforms

| Nuclease Platform | Target Site | Off-Target Count | Specificity Enhancement Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| First-gen ZFNs | HPV URR | 287-1,856 [17] | - |

| Advanced ZFNs | Therapeutic targets | Minimal with optimized designs [16] | Obligate heterodimer FokI domains, optimized linkers [14] [16] |

| TALENs | HPV E7 | 36 [17] | Alternative N-terminal domains, modified repeat variable diresidues [17] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 | HPV E7 | 4 [17] | High-fidelity Cas9 variants, modified guide RNAs [17] [20] |

Experimental Design and Workflow

ZFN Engineering and Validation Protocols

The development of effective ZFNs follows a multi-stage process beginning with target site selection. Optimal ZFN target sequences follow the pattern (NNC)~3~N~6~(GNN)~3~, where the N~6~ spacer region is cleaved and the flanking sequences are recognized by zinc-finger arrays [18]. Contemporary approaches have dramatically expanded targeting possibilities through engineered architectures that allow functional attachment of FokI to the N-terminus of ZFPs and base-skipping between fingers, increasing configurational options by 64-fold [16].

Validation of ZFN activity typically employs a combination of in vitro and cellular assays. A standard protocol involves quantitative real-time PCR with primers flanking the target site to detect disruption of the endogenous locus [18]. The T7 endonuclease I (T7EI) assay is commonly used to detect mutation frequencies by cleaving heteroduplex DNA formed by annealing of wild-type and mutant sequences [17]. For therapeutic applications, ZFNs are often delivered via viral vectors, with adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) being particularly suitable due to the compact size of ZFN genes [18] [16].

Figure 2: ZFN Experimental Workflow. Key stages in ZFN experimentation include (1) target design and nuclease assembly, (2) delivery into target cells, and (3) comprehensive validation of editing efficiency and specificity.

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful ZFN experiments require carefully selected reagents and methodologies. The following table outlines core components of a typical ZFN workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ZFN Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| ZFN Expression Plasmids | pPDAZ vector system [21] | Provides regulated ZFN expression with selection markers |

| Delivery Tools | AAV vectors, lentiviruses, electroporation systems | Efficient ZFN delivery to target cells |

| Validation Assays | T7 endonuclease I, GUIDE-seq, dsODN breakpoint PCR [17] | Detection of on-target and off-target editing events |

| Cell Culture Resources | HER cells, iPSCs, primary T-cells [14] [18] | Relevant cellular models for editing experiments |

| Selection Systems | ccdB counter-selection, antibiotic resistance [16] [21] | Enrichment for successfully edited cells |

Therapeutic Applications and Clinical Status

ZFN technology has demonstrated significant potential across diverse therapeutic areas. In HIV treatment, ZFNs designed to disrupt the CCR5 co-receptor have progressed to clinical trials, with engineered T-cells showing resistance to viral infection and reduced HIV DNA in patients [14] [17]. For inherited disorders, ZFNs have successfully corrected disease-related genes in hematopoietic stem cells for β-thalassemia and in photoreceptor cells for retinitis pigmentosa [14] [18]. A phase I clinical trial for hemophilia B represents the first in vivo genome editing approach, utilizing ZFNs to insert a corrective factor IX gene into the albumin locus [16].

The compact size of ZFNs compared to other editors provides distinct advantages for viral delivery, particularly with AAV vectors which have limited packaging capacity [16]. Additionally, the all-protein structure of ZFNs avoids potential immune responses against bacterial-derived Cas proteins and enables targeting of mitochondrial DNA [16]. These features maintain ZFNs as a viable platform for specific therapeutic applications despite the emergence of newer technologies.

Technical Challenges and Recent Advancements

Historical Limitations and Solutions

Early ZFN platforms faced significant challenges in design complexity, with modular assembly requiring specialized expertise and months of effort to develop effective nucleases [15]. Targeting constraints limited density to approximately one targetable site every 200 base pairs in random sequence using open-source components [15]. Off-target cleavage and cellular toxicity presented additional hurdles, particularly with early architectures that permitted FokI homodimerization at non-cognate sites [14].

Contemporary ZFN systems have addressed these limitations through multiple innovations. Expanded architectures now enable targeting at nearly every base step in arbitrary genomic sequences [16]. Advanced delivery methods, including direct protein delivery and mRNA transfection, reduce off-target effects and cellular toxicity [15]. The development of enhanced FokI domains through directed evolution has yielded variants with substantially improved activity, such as the "Sharkey" domain demonstrating 15-fold increased cleavage efficiency [21].

Emerging Enhancements and Future Directions

Recent research continues to refine ZFN technology through structural diversification and specificity enhancements. New linker configurations enabling functional N-terminal FokI fusions and base-skipping between zinc fingers have expanded design options by 64-fold [16]. Bacterial selection systems utilizing ccdB toxicity allow efficient screening of optimized ZFN architectures from large randomized libraries [16] [21]. These advances maintain ZFNs as a competitive platform for applications requiring high precision and validated specificity, particularly in therapeutic contexts where their compact size and protein-only composition offer distinct advantages.

ZFNs established the foundational paradigm for targeted genome editing and continue to evolve as a valuable platform despite the emergence of TALENs and CRISPR systems. While CRISPR-Cas9 offers superior design simplicity and multiplexing capability, ZFNs maintain advantages in specific contexts including compact size for viral delivery, long recognition sequences for enhanced specificity, and well-characterated safety profiles in clinical applications [17] [16]. The continuing refinement of ZFN architectures, cleavage domains, and delivery methods ensures their ongoing relevance in the genome editing toolkit, particularly for therapeutic applications requiring high precision and minimal off-target effects. As the pioneering technology that demonstrated the feasibility of programmable genome editing, ZFNs remain an important option for researchers and clinicians seeking to implement targeted genetic modifications.

Genome engineering has become an indispensable tool in biological and biomedical research, enabling precise modifications to genomic DNA across a wide variety of organisms [22] [1]. At the heart of programmable gene-editing technologies lie two fundamental components: a targeting mechanism for specific DNA recognition and a nuclease domain for cleaving the DNA backbone. The evolution of these technologies—from zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) to the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas system—represents a shift in how these two components are engineered and function together [23].

This guide provides a structured comparison of the DNA-binding domains (protein-based versus RNA-based) and cleavage mechanisms (FokI versus Cas9) that define these major gene-editing platforms. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding these core architectural principles is essential for selecting the appropriate tool for specific experimental or therapeutic applications, particularly when considering factors such as efficiency, specificity, delivery constraints, and intellectual property landscape [3].

Core Architectural Principles

DNA Recognition Mechanisms

The systems diverge fundamentally in their approach to DNA recognition, which directly impacts their design flexibility, targeting range, and ease of use.

Protein-Based DNA Recognition (ZFNs & TALENs): These platforms rely on custom-designed protein modules to recognize specific DNA sequences.

- Zinc Finger (ZF) Domains: Each zinc finger domain, consisting of approximately 30 amino acids, recognizes a 3-base pair DNA sequence through interactions between its α-helix and the major groove of DNA. Typical ZFNs link three to six of these domains to target sequences of 9 to 18 base pairs [1] [23].

- Transcription Activator-Like Effector (TALE) Domains: TALE proteins use a modular repeat structure where each repeat of 33-35 amino acids recognizes a single nucleotide. The specificity is determined by the 12th and 13th amino acids, known as repeat-variable di-residues (RVDs), which follow a recognizable code (e.g., NI for A, HD for C, NG for T, and NN for G) [1].

RNA-Guided DNA Recognition (CRISPR-Cas9): The CRISPR-Cas9 system simplifies DNA recognition by using a single-guide RNA (sgRNA). This sgRNA contains a ~20 nucleotide spacer sequence that pairs with the target DNA strand through Watson-Crick base pairing. The target site must be adjacent to a short protospacer adjacent motif (PAM), which for the commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 is 5'-NGG-3' [22] [23]. This mechanism decouples the recognition and cleavage functions, as the same Cas9 protein can be directed to any genomic locus simply by changing the sgRNA sequence.

DNA Cleavage Mechanisms

The enzymatic cleavage of DNA is the critical step that initiates genome editing, and the different systems employ distinct strategies with important implications for specificity.

FokI Nuclease Domain (ZFNs & TALENs): Both ZFNs and TALENs are fused to the catalytic domain of the FokI restriction endonuclease [1] [23]. Crucially, the FokI domain must dimerize to become active and create a double-strand break (DSB) [22]. This requires a pair of ZFN or TALEN monomers to bind opposite strands of the DNA in a head-to-head orientation, with a specific spacer sequence separating the two binding sites (typically 5–7 bp for ZFNs and 12–19 bp for TALENs) [22] [1]. This obligate dimerization inherently increases specificity, as two independent binding events must occur simultaneously for cleavage to happen.

Cas9 Nuclease (CRISPR-Cas9): The Cas9 protein is a single effector nuclease that possesses two distinct catalytic domains: the HNH domain, which cleaves the DNA strand complementary to the sgRNA, and the RuvC domain, which cleaves the non-complementary strand [22]. Unlike FokI, Cas9 functions as a monomer. A single Cas9-sgRNA complex is sufficient to generate a DSB, which contributes to its simplicity but can also increase the potential for off-target effects, as a single binding event is enough to trigger cleavage [22] [23].

Table 1: Comparative Anatomy of Gene-Editing Tool Components

| Feature | ZFN | TALEN | CRISPR-Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA-Binding Domain | Zinc Finger Protein | TALE Protein | guide RNA (sgRNA) |

| Recognition Code | 3 bp per zinc finger module | 1 bp per TALE repeat (via RVDs) | ~20 nt sgRNA spacer via base pairing |

| Cleavage Domain | FokI | FokI | Cas9 (RuvC & HNH) |

| Cleavage Mechanism | Obligate Dimerization | Obligate Dimerization | Monomeric |

| Target Site Requirement | Pairs of sites with 5-7 bp spacer | Pairs of sites with 12-19 bp spacer; must begin with 'T' [1] | NGG PAM sequence adjacent to target |

| Overall Target Size | 18-24 bp | 30-40 bp | ~23 bp (20 bp guide + NGG PAM) |

Comparative Performance Data

The architectural differences between these systems translate directly into their practical performance in genome-editing applications, influencing efficiency, specificity, and ease of design.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Major Gene-Editing Platforms

| Performance Metric | ZFN | TALEN | CRISPR-Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specificity / Off-Target Effect | Lower than CRISPR-Cas9 [1] | Lower than CRISPR-Cas9 [1] | High (more prone to off-targets due to mismatch tolerance) [22] [1] |

| Design Complexity | Complex [1] (can take ~1 month [1]) | Complex [1] (can take ~1 month [1]) | Very simple (within a week) [1] |

| Ease of Delivery | Limited due to difficulty of linking ZF modules [22]; but smaller size is advantageous for viral vectors [3] | Difficult due to large cDNA size and extensive repeats [22] [1] | Easy, using standard delivery and cloning techniques [22] |

| Cost | High [1] | Medium [1] | Low [1] |

| Multiplexing Potential | Difficult [22] | Difficult [22] | Easy, can form multiplexes directed to multiple genes [22] |

| Key Limitations | Off-target effects, limited delivery due to size constraints, complex design [22] | Off-target effects, expensive, difficult delivery due to large size [22] [1] | Off-target effects due to mismatch tolerance, constrained by PAM sequence availability [22] [1] |

A key advancement in enhancing specificity is the engineered FokI-dCas9 (fdCas9) system. In this chimeric protein, the nuclease domains of Cas9 are inactivated (creating "dead" Cas9 or dCas9) and fused to the FokI nuclease domain. Like ZFNs and TALENs, this system requires two fdCas9-sgRNA complexes to bind the DNA in a PAM-out orientation with a defined spacer (e.g., 15-25 bp) for FokI dimerization to occur and generate a DSB. This strategy has been shown to significantly reduce off-target effects while maintaining robust on-target editing [22].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To illustrate how these molecular architectures are translated into practical experiments, below are detailed methodologies for key assays evaluating nuclease activity and specificity.

Protocol 1: Evaluating fdCas9 Specificity

This protocol is adapted from Guilinger et al. (2014), who developed one of the first fdCas9 systems and compared its off-target activity to wild-type (WT) Cas9 and paired Cas9 nickases [22].

- Objective: To quantify and compare the on-target and off-target editing rates of WT Cas9, paired nickases, and fdCas9 at endogenous human gene loci (e.g., VEGFA, EMX1).

- Materials:

- Plasmids encoding WT Cas9, Cas9 nickase (D10A mutant), or fdCas9.

- Dual sgRNA expression plasmids or a Csy4-based dual sgRNA expression system [22].

- Human cell line (e.g., HEK293T).

- Transfection reagent.

- Lysis buffer and DNA purification kit.

- PCR primers flanking the on-target and predicted off-target sites.

- T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI) or materials for high-throughput sequencing.

- Methodology:

- Transfection: Co-transfect cells with the nuclease plasmid (WT Cas9, nickase pair, or fdCas9) and the appropriate sgRNA plasmid(s). Include a non-treated control.

- Harvesting: Incubate for 72 hours, then harvest genomic DNA.

- Amplification: Perform PCR to amplify the on-target and known off-target genomic regions from the purified DNA.

- Heteroduplex Formation: Denature and reanneal the PCR products to form heteroduplexes if indels are present.

- Digestion & Analysis: Treat the heteroduplex DNA with T7EI, which cleaves mismatched DNA. Analyze the cleavage products by gel electrophoresis. Alternatively, subject the PCR products to high-throughput sequencing for a more quantitative and unbiased measurement of indel frequencies.

- Key Findings: The fdCas9 system demonstrated a ~140-fold increase in the on-target to off-target editing ratio compared to WT Cas9, and a 1.3 to 8.8-fold increase compared to paired nickases, indicating superior specificity [22].

Protocol 2: Testing T2A-Coupled ZFN Monomers

This protocol is based on a 2025 study that optimized ZFN delivery by expressing both monomers from a single open reading frame linked by a self-cleaving T2A peptide [3].

- Objective: To assess the genome editing efficiency of a single-plasmid T2A-coupled ZFN system compared to the traditional two-plasmid system.

- Materials:

- Two plasmids encoding separate ZF-ND1 (a ZFN variant) monomers (Left-ZF-ND1RRR and Right-ZF-ND1DDD).

- A single plasmid encoding T2A-coupled ZF-ND1 monomers.

- HEK293T or Jurkat cells.

- Transfection reagents.

- Genomic DNA extraction kit.

- PCR primers for the target locus (e.g., AAVS1).

- T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI) assay reagents.

- Methodology:

- Transfection: Transfect cells with either the two separate plasmids or the single T2A-coupled plasmid, using a reduced total DNA amount (by half) for the T2A construct.

- Incubation: Culture cells for 72 hours post-transfection.

- DNA Extraction: Isolate genomic DNA.

- T7EI Assay: Amplify the target locus by PCR, form heteroduplexes, digest with T7EI, and analyze by gel electrophoresis to quantify indel efficiency.

- Off-Target Assessment: Amplify the top predicted off-target sites (e.g., identified via BLAST) and subject them to the T7EI assay to check for unintended mutations.

- Key Findings: The T2A-coupled ZFNs achieved equivalent editing efficiency to the two-plasmid system while using half the total plasmid DNA. The cleaved T2A peptide did not inhibit ND1 nuclease dimerization, whereas a P2A peptide linker significantly reduced efficiency. No off-target mutations were detected for either system under these assay conditions [3].

Visualization of Mechanisms and Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core mechanisms and experimental workflows discussed in this guide.

DNA Recognition and Cleavage Mechanisms

Diagram 1: DNA recognition and cleavage mechanisms. Protein-based systems require two monomers for FokI dimerization, while CRISPR-Cas9 uses a single RNA-guided complex.

High-Specificity fdCas9 Experimental Workflow

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for evaluating nuclease activity and specificity, using fdCas9 as an example.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful genome-editing experiments require a suite of carefully selected reagents. The table below details key materials and their functions, drawing from the experimental protocols cited in this guide.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Genome-Editing Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| TALEN or ZFN Plasmids | Engineered plasmids encoding the left and right monomers of the nucleases. | Inducing DSBs at a specific genomic locus in human cells [4]. |

| fdCas9 Plasmid & Dual sgRNA System | Plasmid encoding the FokI-dCas9 fusion protein and a system (e.g., Csy4-based) to express two sgRNAs. | High-specificity genome editing requiring two adjacent binding sites for FokI dimerization [22]. |

| T2A-Coupled ZFN Plasmid | A single plasmid expressing both ZFN monomers from one open reading frame via a self-cleaving T2A peptide. | Simplified delivery of ZFNs, reducing plasmid size and total DNA amount, beneficial for viral packaging [3]. |

| Circular ssDNA (CssDNA) Donor Template | A kilobase-long circular single-stranded DNA molecule used as a homology-directed repair (HDR) template. | Efficient, non-viral targeted gene insertion in HSPCs with reduced toxicity compared to linear templates [4]. |

| T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI) | An enzyme that cleaves mismatched heteroduplex DNA formed by PCR products from edited and unedited alleles. | Detecting and quantifying the frequency of non-homologous end joining (NHEJ)-induced indels at the target site [3]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Non-viral delivery vehicles that form lipid droplets around CRISPR molecules for in vivo delivery. | Systemic in vivo delivery of CRISPR components, particularly to the liver, as used in clinical trials for hATTR [24]. |

From Bench to Bedside: Current Applications in Research and Therapeutics

In the competitive field of preclinical therapeutic development, the selection of an appropriate gene-editing technology is paramount to project success. Clustered regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR-Cas9) has emerged as the dominant platform, particularly for gene knockout applications, surpassing older technologies like Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs) and Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) in widespread adoption [25]. This dominance stems from a combination of design simplicity, high efficiency, and versatility that accelerates research timelines. While all three technologies create double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA to initiate gene disruption, their underlying mechanisms, practical implementation, and performance characteristics differ significantly [26] [27]. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these platforms, focusing on their application in knockout studies essential for target validation, disease modeling, and functional genomics in preclinical drug discovery.

Technology Comparison: Mechanisms and Workflows

Core Mechanisms of Action

The foundational difference between these technologies lies in their DNA recognition and cleavage mechanisms:

- CRISPR-Cas9 is a two-component system utilizing a guide RNA (gRNA) for sequence-specific targeting and the Cas9 nuclease for DNA cleavage. The gRNA binds to the target DNA via Watson-Crick base pairing, making design straightforward and predictable [2] [28].

- TALENs are fusion proteins consisting of a TALE DNA-binding domain and a FokI nuclease domain. The TALE domain comprises repeating units, each recognizing a single nucleotide, providing high specificity but requiring more complex protein engineering [2] [26].

- ZFNs also employ the FokI nuclease, fused to a zinc-finger DNA-binding domain. Each zinc finger recognizes a nucleotide triplet, and ZFNs must function as pairs, necessitating extensive protein engineering for each new target [2] [27].

The following diagram illustrates the key mechanistic differences and the general workflow for applying each technology in a knockout experiment.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Direct comparative studies provide objective data on the performance of ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR-Cas9. A 2021 study utilizing the GUIDE-seq method for unbiased off-target detection offers a clear efficiency and specificity comparison when targeting the human papillomavirus (HPV16) genome [17].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of ZFNs, TALENs, and SpCas9 in HPV16 Gene Therapy Model

| Technology | Target Gene | On-Target Efficiency | Off-Target Count (GUIDE-seq) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZFN | URR | High | 287 - 1,856 |

| TALEN | URR | High | 1 |

| TALEN | E6 | High | 7 |

| TALEN | E7 | High | 36 |

| SpCas9 | URR | High | 0 |

| SpCas9 | E6 | High | 0 |

| SpCas9 | E7 | High | 4 |

This data demonstrates that SpCas9 was more efficient and specific than ZFNs and TALENs in this model, with fewer off-target events across all target genes [17]. The study also noted that ZFN specificity could be inversely correlated with the count of middle "G" in zinc finger proteins, and that TALEN designs to improve efficiency (e.g., using αN or NN modules) inevitably increased off-target counts [17].

Practical Workflow and Feasibility

From a practical standpoint, CRISPR-Cas9 offers significant advantages in ease of use and speed, which directly contributes to its dominance in knockout applications.

Table 2: Feasibility and Workflow Comparison for Knockout Generation

| Parameter | CRISPR-Cas9 | TALENs | ZFNs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Design | Simple gRNA design via base pairing [27] | Complex protein engineering for each target [2] | Highly complex protein engineering [2] |

| Development Timeline | Days to a week [28] | Several weeks [2] | Several months [2] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | High (multiple gRNAs simultaneously) [27] | Low | Low |

| Efficiency in Immortalized Cells | High (>80% INDEL efficiency common) [29] | Variable, generally high [2] | Variable [2] |

| Efficiency in Primary Cells | Moderate to high, but more challenging [25] | Lower than CRISPR | Lower than CRISPR |

| Typical Knockout Workflow Duration | ~3 months (median reported) [25] | >6 months (estimated) | >6 months (estimated) |

Survey data from the drug discovery sector confirms that CRISPR is the primary genetic modification method for 45.4% of commercial and 48.5% of non-commercial institutions, with knockouts being the most widely used application (45%-54% of researchers using CRISPR) [25]. The data also reveals that researchers typically repeat the entire CRISPR workflow a median of 3 times before succeeding, underscoring that while highly efficient, the process still requires optimization and validation [25].

Experimental Protocols for Knockout Validation

GUIDE-seq for Comprehensive Off-Target Analysis

The GUIDE-seq (Genome-Wide Unbiased Identification of DSBs Enabled by Sequencing) method provides a robust protocol for identifying off-target effects of CRISPR nucleases, TALENs, and ZFNs [17]. This is critical for preclinical safety assessment.

Protocol Overview:

- dsODN Transfection: Co-deliver programmed nuclease components (e.g., Cas9/gRNA RNP, TALEN mRNA, ZFN mRNA) with a short, double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (dsODN) tag into mammalian cells.

- Tag Integration: The dsODN tag integrates into nuclease-induced double-strand break (DSB) sites via the NHEJ repair pathway.

- Genomic DNA Extraction and Library Preparation: Harvest cells 72-96 hours post-transfection. Extract genomic DNA and shear it by sonication.

- Enrichment and Sequencing: Enrich for dsODN-integrated fragments using PCR. Prepare sequencing libraries and perform high-throughput sequencing.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Map sequencing reads to the reference genome to identify all dsODN integration sites, which correspond to both on-target and off-target nuclease activity.

Key Considerations:

- The distribution of GUIDE-seq read start positions reveals distinct DSB patterns: SpCas9 shows minimal variability, while ZFNs and TALENs exhibit higher variability in cleavage sites [17].

- This method can detect off-targets with frequencies as low as 0.0001% and was successfully adapted for TALENs and ZFNs by developing novel bioinformatics algorithms [17].

Indel Analysis for On-Target Efficiency

Quantifying insertion or deletion mutations (indels) at the target site is a standard practice for evaluating knockout efficiency. CRISPR-GRANT is a graphical analysis tool that simplifies this process for novice users [30].

Protocol Overview:

- Amplicon Sequencing: Design PCR primers flanking the target site and perform targeted amplification from edited genomic DNA. Submit the amplicon library for next-generation sequencing (NGS).

- Data Processing with CRISPR-GRANT:

- Input: Provide raw FASTQ files and the reference target sequence in FASTA format.

- Quality Control: The tool uses Fastp for quality control, removing low-quality reads.

- Read Mapping: BWA-MEM aligns reads to the reference sequence.

- Variant Calling: VarScan2 analyzes the aligned reads for consensus and variants.

- Quantification and Visualization: CRISPR-GRANT generates:

- A table of different indel types and their read counts.

- The percentage of modified and un-modified reads.

- Alignment visualization of top reads.

- Frequency of indels at each position along the reference.

Advantages: CRISPR-GRANT offers a standalone graphical interface, requires no data pre-processing, supports analysis of single/pooled amplicons and whole-genome sequencing, and operates offline to protect sensitive data [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of gene knockout experiments requires a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions for CRISPR-based knockout studies, which represent the current dominant workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR Knockout Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | Creates double-strand breaks at target DNA. | SpCas9 is the standard; also Cas12a (Cpf1) [30]. HiFi Cas9 variants reduce off-targets [31]. |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | Directs Cas9 to specific genomic locus via base pairing. | Chemically synthesized, in vitro transcribed, or expressed from a vector [28]. |

| Delivery Vehicle | Introduces editing components into cells. | Lentivirus, AAV, lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), electroporation of ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes [28]. |

| NGS Library Prep Kit | Prepares amplicon libraries for sequencing to assess editing. | Kits for Illumina, PacBio, or other NGS platforms [17]. |

| Off-Target Detection Tool | Identifies unintended edits genome-wide. | GUIDE-seq [17], CAST-Seq [31]. |

| Cell Culture Reagents | Maintains and expands target cells for editing. | Cell-type specific media; primary cells are more challenging than immortalized lines [25]. |

| Bioinformatics Software | Analyzes NGS data to quantify editing efficiency and specificity. | CRISPR-GRANT [30], CRISPResso2 [30]. |

Limitations and Safety Considerations

Despite its dominance, CRISPR-Cas9 is not without limitations. A significant concern beyond off-target effects is the generation of on-target structural variations (SVs) [31]. These can include large deletions, chromosomal translocations, and other complex rearrangements that are difficult to detect with standard short-read amplicon sequencing [31]. Such SVs have also been observed with ZFNs and TALENs, indicating this is a risk associated with DSB-inducing nucleases generally [31].

Furthermore, strategies to enhance homology-directed repair (HDR), such as using DNA-PKcs inhibitors, can dramatically increase the frequency of these kilobase- to megabase-scale deletions and chromosomal translocations [31]. This highlights a critical trade-off where efforts to improve precise editing can inadvertently introduce new genomic risks, emphasizing the need for comprehensive genomic integrity assessments in preclinical development.

The quantitative data and experimental comparisons presented in this guide unequivocally support the conclusion that CRISPR-Cas9 is the leading technology for gene knockout applications in preclinical research. Its superiority stems from a combination of high efficiency, specificity, straightforward design, and multiplexing capability, which collectively accelerate research timelines compared to TALENs and ZFNs [17] [25] [27].

The field continues to evolve rapidly with the development of base editing, prime editing, and other precision editing tools that can modify DNA without creating double-strand breaks, potentially offering improved safety profiles [32]. However, for routine gene knockout applications essential to target validation and functional genomics, CRISPR-Cas9 remains the most versatile and effective platform. As with any powerful technology, its successful application requires careful experimental design, robust validation using the described protocols, and a thorough assessment of both on-target and off-target outcomes to ensure the reliability of preclinical data.

The field of genome editing has transitioned from theoretical promise to clinical reality, with CRISPR-based therapies now demonstrating transformative potential for treating genetic disorders. As of 2025, the clinical landscape represents both remarkable achievements and significant challenges [24]. The landmark approval of Casgevy (exagamglogene autotemcel) for sickle cell disease (SCD) and transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia (TBT) has established a new paradigm for genetic medicine, while investigational therapies for hATTR and HAE are showing promising results in ongoing trials [24]. This review analyzes the latest clinical trial data for these three key applications, providing a comparative assessment of their efficacy, safety profiles, and underlying technological approaches within the broader context of genome editing platforms.

The current state represents "the best of times and the worst of times" for CRISPR medicine [24]. While scientific progress continues at an impressive pace, with promising results across multiple disease areas, significant headwinds have emerged from reduced venture capital investment and government funding cuts that threaten to slow future innovation [24]. Despite these challenges, the clinical data emerging from trials provide compelling evidence for the therapeutic potential of precise genetic modifications.

Comparative Analysis of Clinical Trial Outcomes

Table 1: Summary of Key Clinical Trial Outcomes for CRISPR Therapies

| Therapy & Indication | Developer | Phase | Key Efficacy Results | Primary Safety Concerns | Delivery Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casgevy (SCD) | CRISPR Therapeutics & Vertex | Approved | 94% (29/31) freedom from severe VOCs for ≥12 months; 100% (30/30) free of VOC-related hospitalizations [33] | Hematological toxicity (low platelets/white blood cells) due to conditioning chemotherapy [33] | Ex vivo edited CD34+ cells |

| Casgevy (TBT) | CRISPR Therapeutics & Vertex | Approved | 91% (32/35) transfusion-free for ≥12 months; sustained independence for median 20.8 months [34] | Hematological toxicity (low platelets/white blood cells) due to conditioning chemotherapy [34] | Ex vivo edited CD34+ cells |

| NTLA-2001 (hATTR) | Intellia Therapeutics | Phase III | ~90% sustained reduction in TTR protein levels at 2 years; functional stabilization or improvement [24] | Mild-moderate infusion-related reactions [24] | In vivo LNP delivery |

| NTLA-2002 (HAE) | Intellia Therapeutics | Phase I/II | 86% reduction in kallikrein; 8/11 patients attack-free for 16 weeks at higher dose [24] | Under further characterization in ongoing trials [24] | In vivo LNP delivery |

Table 2: Molecular and Technological Characteristics of CRISPR Therapies

| Therapy | Genetic Target | Editing Approach | Biological Mechanism | Dosing Regimen |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casgevy | BCL11A gene | CRISPR-Cas9 knockout | Increases fetal hemoglobin (HbF) production to compensate for defective adult hemoglobin [33] [34] | Single administration of ex vivo edited cells |

| NTLA-2001 | TTR gene | CRISPR-Cas9 knockout | Reduces production of misfolding-prone transthyretin protein [24] | Single IV infusion (redosing possible with LNP) |

| NTLA-2002 | KLKB1 gene | CRISPR-Cas9 knockout | Reduces plasma kallikrein to prevent inflammatory attacks [24] | Single IV infusion (redosing possible with LNP) |

CRISPR Versus Alternative Genome Editing Platforms

The development of therapeutic genome editing has been propelled by three major nuclease platforms: Zinc-Finger Nucleases (ZFNs), Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs), and CRISPR-Cas systems. Understanding their relative advantages and limitations provides essential context for interpreting current clinical trial approaches.

Technology Comparison and Historical Development

ZFNs were the first engineered nucleases to enable targeted genome editing, utilizing modular zinc-finger proteins that typically recognize 3-6 nucleotide triplets [35] [27]. Each ZFN domain recognizes 3-6 nucleotide triplets, requiring paired ZFNs to target a specific locus [27]. TALENs subsequently emerged with a potentially simpler design principle, utilizing repeat domains that each recognize a single nucleotide [35] [27]. The more recent CRISPR-Cas9 system differs fundamentally by utilizing a guide RNA (gRNA) for target recognition, with the Cas9 nuclease providing the DNA cleavage function [27].

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Major Genome Editing Platforms

| Characteristic | Zinc-Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) | TALENs | CRISPR-Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Recognition | Protein-based (3-6 bp per module) | Protein-based (1 bp per repeat) | RNA-based (20 bp gRNA) |

| Target Design Simplicity | Complex, context-dependent effects | Moderate, more straightforward than ZFNs | Simple, easily programmable gRNAs |

| Efficiency | Variable | Variable | High efficiency across targets |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Limited | Limited | High (multiple gRNAs simultaneously) |

| Off-Target Effects | Moderate concern | Lower concern due to longer recognition | Variable; dependent on gRNA design |

| Clinical Stage | Earlier-stage development | Earlier-stage development | Multiple approved therapies and late-stage trials |

Advantages of CRISPR in Therapeutic Applications

CRISPR-Cas9 offers several distinct advantages that have accelerated its clinical translation. The simplicity of retargeting the system with different gRNAs has dramatically reduced the time and cost required to develop new therapeutic candidates [27]. The high efficiency of CRISPR editing enables more consistent results across targets, while the capacity for multiplexing allows for simultaneous editing of multiple genomic loci [27]. These technical advantages, combined with the demonstrated clinical efficacy in multiple trials, explain CRISPR's current dominance in the therapeutic genome editing landscape.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Casgevy Treatment Protocol and Clinical Assessment

The Casgevy treatment process involves a multi-step protocol extending over several months [33] [34]. Initially, patients undergo hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) mobilization using medicines that move blood stem cells from bone marrow to the bloodstream [33]. The collected CD34+ HSCs are then shipped to a manufacturing facility where CRISPR-Cas9-mediated editing targets the BCL11A gene to increase fetal hemoglobin production [33]. Patients subsequently receive myeloablative conditioning with busulfan to clear bone marrow space before infusion of the edited cells [33]. The entire process from cell collection to infusion takes approximately 6 months [33].

Efficacy assessment for SCD trials focused on freedom from severe vaso-occlusive crises (VOCs), defined as pain events requiring medical facility visits, acute chest syndrome, priapism, or splenic sequestration [33]. For beta thalassemia, the primary endpoint was transfusion independence for at least 12 consecutive months [34]. Safety monitoring emphasized hematological parameters due to the myelosuppressive effects of conditioning chemotherapy [33] [34].

Figure 1: Casgevy Therapeutic Workflow - This diagram illustrates the multi-step process for Casgevy administration, from stem cell collection through engraftment monitoring.

In Vivo CRISPR Delivery and Assessment

Intellia's therapies for hATTR and HAE utilize a fundamentally different approach through in vivo delivery via lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) [24]. The LNP-formulated CRISPR components are administered via single intravenous infusion, with the nanoparticles naturally accumulating in liver cells where the target proteins are primarily produced [24]. This approach enables potential redosing, as demonstrated by the administration of multiple doses to patients in the hATTR trial and to infant KJ in the personalized CPS1 deficiency case [24].

Efficacy assessment for hATTR focuses on reduction in TTR protein levels in blood, which correlates with disease severity [24]. For HAE, researchers monitor kallikrein reduction and frequency of inflammatory attacks [24]. The non-invasive nature of these protein-level biomarkers facilitates convenient monitoring of treatment efficacy.

Technological Innovations in CRISPR Delivery

Lipid Nanoparticle Delivery Systems

A critical advancement enabling in vivo CRISPR therapies has been the development of lipid nanoparticle (LNP) delivery systems [24]. LNPs are tiny fat particles that form protective droplets around CRISPR components, naturally accumulating in the liver after systemic administration [24]. This organotropism makes LNPs particularly suitable for diseases where the relevant proteins are produced primarily in the liver, including hATTR, HAE, and various cholesterol disorders [24].

Unlike viral delivery vectors, which typically trigger immune responses that prevent redosing, LNPs do not elicit the same immune concerns, allowing for multiple administrations as demonstrated in clinical trials [24]. This represents a significant advantage for dose optimization and potentially for managing progressive diseases requiring sustained editing.

Figure 2: In Vivo LNP Delivery Mechanism - This diagram illustrates the pathway of LNP-formulated CRISPR components from intravenous administration to therapeutic effect in liver cells.

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for CRISPR Therapeutic Development

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Research Function | Therapeutic Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Nucleases | Cas9, base editors, prime editors | DNA cleavage or precise modification | Varies by therapeutic strategy |

| Delivery Systems | LNPs, AAVs, electroporation | Intracellular delivery of editing components | Determined by target tissue and editing approach |

| gRNA Design Tools | VBC scores, Rule Set 3 algorithms | Predicting on-target efficiency and off-target risk | Critical for therapeutic safety profile |

| Library Platforms | Vienna-single, Vienna-dual, Yusa V3 | High-throughput functional screening | Target identification and validation |

| Analytical Methods | NGS off-target assays, RNA sequencing | Comprehensive safety profiling | Regulatory requirement for clinical development |

The development of optimized sgRNA libraries has been particularly important for advancing therapeutic applications. Recent benchmark comparisons demonstrate that Vienna-single and Vienna-dual libraries perform as well as or better than larger libraries while reducing costs and improving feasibility for complex models [36]. Dual-targeting libraries, where two sgRNAs target the same gene, show enhanced knockout efficiency but may trigger a more pronounced DNA damage response [36].

The clinical trial data for hATTR, HAE, and sickle cell disease demonstrate that CRISPR-based therapies have achieved a critical milestone in transitioning from concept to clinical reality. The substantial efficacy demonstrated across these diverse conditions, along with acceptable safety profiles, suggests that genome editing is poised to become an established therapeutic modality. The parallel development of ex vivo (Casgevy) and in vivo (Intellia therapies) approaches demonstrates the versatility of CRISPR platforms for different disease contexts.

Future directions will likely focus on expanding delivery options beyond current liver-tropic LNPs, developing more precise editing tools like base and prime editors, and optimizing redosing strategies for sustained therapeutic effects [24] [37]. Additionally, resolving challenges related to funding constraints and manufacturing scalability will be essential for ensuring broad patient access to these transformative therapies [24]. As the field matures, the integration of CRISPR therapeutics into mainstream medicine will depend on both technical innovations and the development of sustainable implementation models.

The advent of precise gene editing technologies has revolutionized molecular biology, offering unprecedented potential for treating genetic diseases. Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR-Cas) systems, Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs), and Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) represent the leading platforms for therapeutic genome engineering [1] [13]. While each system can induce targeted DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs), their practical application in vivo, particularly for human therapies, depends critically on safe and efficient delivery vehicles [38]. Viral vectors, especially adeno-associated viruses (AAVs), have been widely used but face significant limitations including immunogenicity, limited payload capacity, and potential for insertional mutagenesis [38] [39]. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) have emerged as a promising non-viral alternative, demonstrating particular utility for liver-targeted therapies due to their natural tropism for hepatic tissue [38] [39] [40]. This review comprehensively compares the efficiency of major gene editing platforms when delivered via LNPs, focusing on their application in liver-directed therapies, and provides experimental data supporting their relative performance.

Comparative Analysis of Major Gene Editing Platforms

The choice of gene editing technology significantly impacts experimental design, efficiency, and therapeutic applicability. Below, we systematically compare the key characteristics of ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR-Cas systems.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Genome Editing Platforms

| Feature | Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) | TALENs | CRISPR-Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Recognition Mechanism | Protein-based (Zinc finger protein) [1] | Protein-based (TALE protein) [1] | RNA-based (guide RNA) [1] [13] |

| Nuclease Domain | FokI [1] | FokI [1] | Cas9 [1] [13] |

| Design Complexity | Complex (∼1 month) [1] | Complex (∼1 month) [1] | Very simple (within a week) [1] |

| Target Design | Requires engineering DNA-binding proteins for each target [1] [13] | Requires engineering DNA-binding proteins for each target [1] [13] | Requires only synthesis of a new guide RNA [13] |

| Cost | High [1] | Medium [1] | Low [1] |

| Off-Target Effects | Lower than CRISPR-Cas9 [1] | Lower than CRISPR-Cas9 [1] | High (concern, but improving with engineered variants) [1] |

| Payload Size for Delivery | Compact (advantage for viral delivery) [1] | Large (challenging for viral delivery) [1] | Large (Cas9 + gRNA) but flexible (can deliver as RNA) [38] [40] |

Key Distinctions and Workflows

The fundamental distinction between these technologies lies in their targeting mechanisms. ZFNs and TALENs rely on custom-designed protein modules to recognize DNA sequences, whereas CRISPR-Cas systems use a guide RNA (gRNA) for recognition, making redesign vastly more straightforward [1] [13]. The simplicity of CRISPR-Cas9, where targeting a new genomic locus requires only the synthesis of a new short gRNA, underpins its rapid adoption and versatility [13].

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanistic differences and experimental workflows for these nuclease platforms.

Diagram 1: Core mechanisms and workflows for ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR-Cas9. All systems create double-strand breaks (DSBs) repaired by Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) or Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) [1].

Lipid Nanoparticles as a Delivery Vehicle for Gene Editing

LNP Composition and Mechanism of Action

LNPs are spherical vesicles, typically 50-120 nm in diameter, composed of a precise mixture of lipids that encapsulate and protect nucleic acid payloads [38]. Their functional core consists of four key components:

- Ionizable Lipids: The most critical component (e.g., ALC-0315, ALC-0307, SM-102). They are positively charged at acidic pH during formulation to enable RNA encapsulation but neutral in blood. In the acidic environment of endosomes, they become protonated, promoting destabilization of the endosomal membrane and release of the payload into the cytoplasm [38] [39] [41].

- Phospholipid: (e.g., DSPC) acts as a structural lipid, contributing to the LNP bilayer stability [38] [42].

- Cholesterol: Enhances the integrity and stability of the nanoparticle and facilitates cellular uptake [38] [39].

- PEG-lipid: Shields the LNP surface, reduces aggregation, controls particle size, and influences pharmacokinetics. It dissociates in vivo to facilitate cellular uptake [38] [39].

The mechanism of LNP-mediated delivery to hepatocytes is highly efficient. Following systemic administration, LNPs are opsonized by apolipoprotein E (ApoE) in the serum. This complex then binds to the very low-density lipoprotein receptor (VLDLR) on hepatocytes, initiating endocytosis [39]. The progressive acidification of the endosome protonates the ionizable lipid, leading to endosomal membrane disruption and release of the nucleic acid payload into the cytosol [38] [43].

Advantages of LNPs Over Viral Vectors for Liver-Targeted Editing

LNPs offer several distinct advantages for delivering gene-editing components, particularly for liver applications, compared to viral vectors like AAVs [38]:

- Low Immunogenicity: AAV capsids can trigger pre-existing or treatment-induced immune responses, potentially neutralizing the therapy. LNPs have a much lower immunogenicity profile, allowing for safer administration and the potential for multiple dosing [38].

- Transient Expression: Viral vectors can lead to long-term, stable expression of editor proteins, increasing the window for potential off-target edits. When LNPs deliver mRNA encoding CRISPR-Cas9, the expression is high but transient, limiting the duration of nuclease activity and reducing off-target risks [38].

- Large Payload Capacity: LNPs can accommodate large payloads, including the mRNA for Cas9 and one or more guide RNAs, which exceeds the modest capacity of AAVs [38].

- Scalable Manufacturing: The manufacturing process for LNPs is rapid (can be completed in days), scalable, and avoids the complexities and time required for AAV production [38].

Experimental Data: LNP-Mediated Delivery for Liver-Targeted Therapies

Quantitative Efficacy of LNP Formulations

Recent preclinical and clinical studies have demonstrated the potent efficacy of LNP-delivered gene editors. The data below summarize key findings from experiments targeting genes in the liver.

Table 2: Experimental Data on LNP-Mediated Gene Editing in the Liver