Combinatorial Optimization of Enzyme Expression Levels: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of combinatorial optimization strategies for balancing enzyme expression levels in engineered metabolic pathways, a critical challenge in metabolic engineering and pharmaceutical development.

Combinatorial Optimization of Enzyme Expression Levels: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of combinatorial optimization strategies for balancing enzyme expression levels in engineered metabolic pathways, a critical challenge in metabolic engineering and pharmaceutical development. We explore the foundational principles of metabolic flux balancing and the 'fitness landscape' concept, which frames pathway optimization as an NP-hard combinatorial problem. The review details cutting-edge methodological approaches, including the construction of combinatorial promoter libraries, the application of regression modeling and active learning algorithms, and high-throughput screening techniques. We further address common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, such as overcoming flux imbalances, cellular burden, and epistatic interactions. Finally, we cover validation and comparative analysis frameworks, emphasizing computational scoring, experimental benchmarking, and the integration of AI-assisted design. This resource is tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to enhance recombinant protein and small-molecule production.

The Foundation of Flux Balance: Why Combinatorial Optimization is Essential for Metabolic Pathways

Understanding Metabolic Flux Imbalances and Cellular Burden in Engineered Pathways

Core Concepts: Metabolic Flux Imbalance and Cellular Burden

What are metabolic flux imbalances and why are they a problem in engineered pathways?

Answer: In engineered metabolic pathways, flux imbalance occurs when the activities of enzymes are not properly matched, leading to two primary issues:

- Overburdening the cell: Highly expressed foreign pathways can consume excessive cellular resources (e.g., energy, precursors), hindering host cell growth and function [1].

- Accumulation of intermediates: When an upstream enzyme is more active than the downstream enzyme, metabolic intermediates build up. This can be detrimental to the cell, as some intermediates may be toxic, and it invariably reduces final product titers [1] [2].

How can I tell if my engineered strain is suffering from a metabolic flux imbalance?

Answer: Common experimental indicators of flux imbalance include:

- Suboptimal product titers despite high enzyme expression levels.

- Detectable accumulation of pathway intermediates using analytical methods like HPLC or GC-MS.

- Reduced host cell growth rate or fitness, suggesting an excessive metabolic burden [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Final Product Titer Despite High Pathway Enzyme Expression

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Rate-Limiting Step | Measure intermediate concentrations to identify the point of accumulation. | Systemically optimize expression of the rate-limiting enzyme [1]. |

| Insufficient Cofactor Regeneration | Analyze intracellular cofactor levels (e.g., NADPH/NADP+). | Introduce or enhance cofactor regeneration systems [3]. |

| Toxic Intermediate Accumulation | Assess correlation between intermediate concentration and cell growth inhibition. | Implement enzyme scaffolding to channel intermediates [3] or re-balance enzyme ratios to minimize buildup [1]. |

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Excessive Metabolic Burden | Measure growth rate and plasmid stability; quantify resource usage. | Fine-tune enzyme expression levels to the minimal sufficient level using combinatorial libraries [1]. |

| Toxicity of Pathway Intermediate or Product | Conduct growth assays in the presence of suspected compounds. | Use synthetic scaffolds to sequester toxic intermediates [3] or export products. |

| Diversion of Essential Metabolites | Track flux through central metabolism using 13C labeling. | Re-engineer central metabolism to increase precursor supply if needed [2]. |

Optimization Strategies & Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for key optimization experiments cited in troubleshooting guides.

Protocol 1: Combinatorial Optimization of Enzyme Expression Levels Using a Regression Model

This protocol is adapted from a study that successfully optimized a five-enzyme pathway in S. cerevisiae without a high-throughput assay [1].

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Characterized Promoter Set: A library of constitutive promoters that maintain relative strengths across different coding sequences (e.g., for S. cerevisiae) [1].

- Standardized Assembly System: A DNA assembly method (e.g., Gibson assembly) with standard restriction sites (e.g., BglBrick, BioBrick) for modular pathway construction [1].

- Regression Software: Standard statistical software (e.g., R, Python with scikit-learn) capable of performing linear regression.

Methodology:

- Library Design and Construction:

- Assemble your target pathway, varying the expression of each enzyme using the characterized promoter library. This creates a combinatorial library of strain variants.

- Sparse Sampling and Phenotyping:

- Randomly select a small, manageable subset of the total library (e.g., 3%) [1].

- Cultivate these selected clones and measure the final product titer using a low-throughput but accurate method (e.g., LC-MS).

- Model Training and Prediction:

- Genotype each sampled clone to determine the promoter identity for each gene.

- Train a linear regression model where the predictors are the expression levels (from promoter strength) for each enzyme and the response variable is the product titer.

- Use the trained model to predict the product titer for all possible genotype combinations in the full library.

- Strain Validation:

- Select the top-performing genotypes predicted by the model.

- Construct and test these strains to validate the model's predictions.

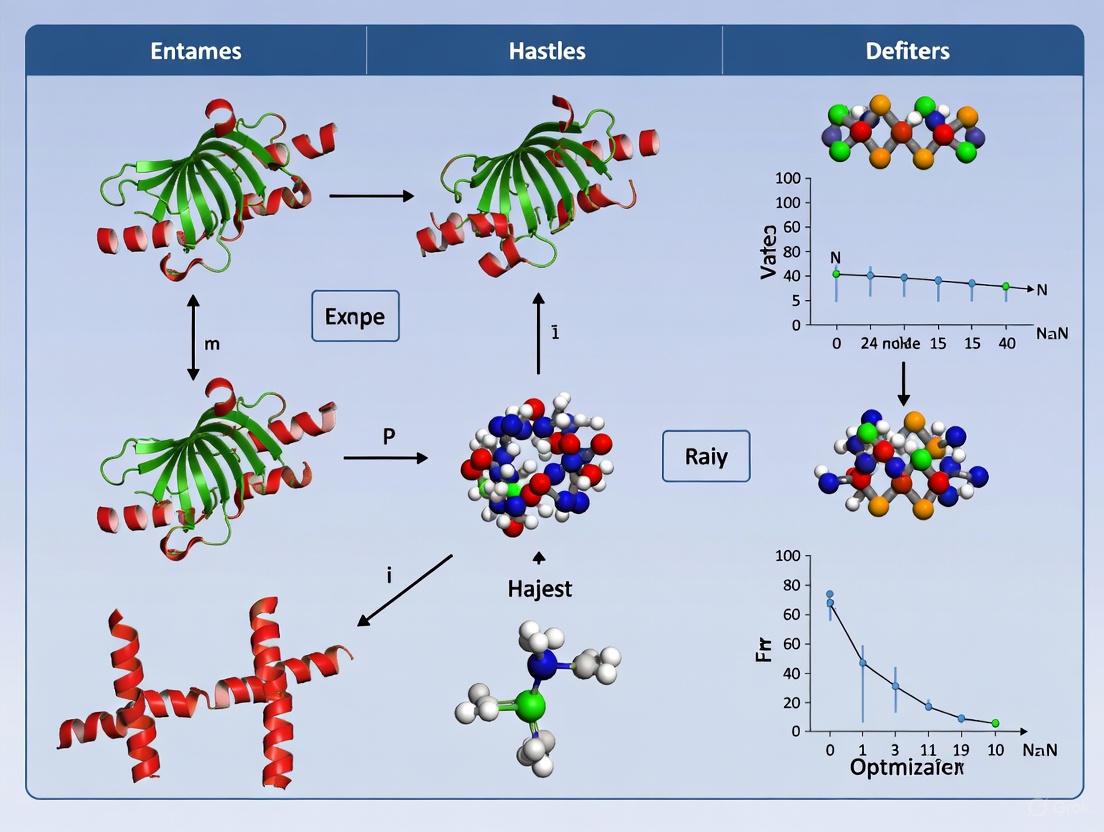

The following workflow diagram illustrates this systematic combinatorial optimization process:

Protocol 2: Implementing Synthetic Scaffolds for Metabolic Channeling

This protocol outlines the use of synthetic scaffolds to co-localize enzymes, thereby increasing local concentrations and facilitating the transfer of intermediates [3].

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Protein-Peptide Pairs: Use interacting protein domains (e.g., PDZ, SH3, GBD) and their cognate peptide ligands to assemble enzymes [3].

- Peptide-Peptide Pairs: Use short, interacting peptide tags (e.g., RIDD/RIAD from PKA system) for scaffold-free enzyme assembly [3].

- DNA Scaffolds: Use designed DNA nanostructures (e.g., origami) with specific docking sites for enzyme fusion proteins.

Methodology:

- Selection of Scaffold Type: Choose a scaffold system (protein, peptide, or DNA) based on the number of enzymes to be assembled and host compatibility.

- Genetic Fusion:

- Fuse your pathway enzymes to the "client" part of the scaffold system (e.g., a peptide ligand).

- Express the "scaffold" part (e.g., the protein domain that binds the ligand) separately, or fuse it for self-assembly.

- Strain Construction and Testing:

- Introduce the fusion constructs into your production host.

- Measure product titer, intermediate accumulation, and cell growth, comparing against a non-scaffolded control.

The diagram below shows the conceptual design of assembling a three-enzyme pathway on a synthetic protein scaffold:

Advanced FAQ

Are there computational tools to predict potential flux imbalances before I start building a pathway?

Answer: Yes, several computational approaches exist. Graph-based pathfinding algorithms can propose novel pathways but also provide insights into network connectivity that might hint at bottlenecks [4]. Furthermore, retrosynthesis-based tools (e.g., BNICE, RetroPath) and databases (e.g., ATLAS) can explore an expanded biochemical space to identify potential routes and evaluate their theoretical feasibility [4].

How does the "UTR Library Designer" method work for optimization?

Answer: The UTR Library Designer is a predictive method for systematically tuning gene expression at the translation level [2].

- Principle: It uses a thermodynamic model to calculate the Gibbs free energy (ΔG) of the mRNA translation initiation region (TIR), which is linearly related to the log-expression level.

- Process: A genetic algorithm designs TIR sequences (5'-UTR and 5'-proximal coding sequence) to achieve a desired range of expression levels with a specified number of intermediates.

- Advantage: This method can cover a much larger expression-level space (e.g., up to 5,000-fold change) with far fewer variants than a random mutagenesis approach, making optimization more efficient [2].

What are the key considerations when choosing between different optimization methods (e.g., promoters, UTRs, scaffolds)?

Answer: The choice depends on your specific goals and constraints. The table below summarizes the key considerations for selecting an optimization method:

| Method | Best For | Key Advantage | Throughput Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Combinatorial Promoters & Regression [1] | Multi-gene pathways; targets without high-throughput assays. | Optimizes the entire system simultaneously; reveals global optima. | Requires only sparse sampling of the library. |

| UTR Library Designer [2] | Fine-tuning translation initiation; achieving massive expression ranges. | Extreme precision and predictability over expression levels. | Library size can be designed to match screening capacity. |

| Synthetic Scaffolds [3] | Pathways with toxic or unstable intermediates; multi-enzyme complexes. | Channels intermediates; protects cells from toxicity; enhances flux. | Requires constructing and testing fusion proteins. |

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key reagents and their functions for experiments focused on combinatorial optimization of enzyme expression.

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Optimization Experiments | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Characterized Promoter Set [1] | Provides a range of known, consistent expression strengths for different genes. | Building a combinatorial library of a violacein pathway in yeast [1]. |

| Standardized Assembly System [1] | Enables rapid, modular, and reliable construction of multi-gene pathways. | Assembling a five-enzyme pathway from multiple parts into a vector [1]. |

| Protein/Peptide Interaction Domains [3] | Serves as the "glue" for synthetic scaffolds (e.g., PDZ, SH3, GBD domains and their ligands). | Co-localizing three enzymes (atoB, HMGS, HMGR) to increase mevalonate production [3]. |

| Interacting Peptide Tags [3] | Enables scaffold-free self-assembly of enzyme complexes (e.g., RIDD and RIAD peptides). | Assembling a two-enzyme system for improved metabolic flux without a physical scaffold [3]. |

| UTR Library Designer Algorithm [2] | Computationally designs mRNA sequences to achieve a precise range of translation efficiency. | Generating a library of 5'-UTR variants for the ppc gene to optimize lysine production [2]. |

Fitness Landscapes and the NP-Hard Nature of Multi-Gene Optimization

What is a Fitness Landscape in the context of metabolic engineering?

In evolutionary biology and metabolic engineering, a fitness landscape is a visual model representing the relationship between genotypes (or enzyme expression combinations) and reproductive success (or production efficiency) [5]. Imagine a landscape where:

- Location represents a specific combination of enzyme expression levels in your pathway

- Height represents the fitness or production titer of your target compound

- Peaks correspond to optimal expression combinations that maximize production

- Valleys represent poor combinations with low yield [5] [6]

This conceptual framework helps researchers visualize why finding optimal enzyme expression levels is challenging—you may be stuck on a small "hill" without knowing a much higher "mountain" exists elsewhere in the landscape [6].

Why is multi-gene combinatorial optimization considered NP-hard?

Multi-gene optimization falls into the NP-hard class of problems because the computational time required to find the optimal solution grows exponentially with the number of genes involved [7]. Key reasons include:

- Combinatorial explosion: For

ngenes each withmpossible expression levels, you facem^npossible combinations to test - Interdependent objectives: Optimizing for titer, rate, and yield creates multiple competing objectives [7]

- Rugged landscapes: Real biological landscapes contain many local optima where algorithms can get stuck [5]

The Travelling Thief Problem and Multi-Skill Resource-Constrained Project Scheduling Problem (MS-RCPSP) are examples of NP-hard problems that share characteristics with metabolic pathway optimization [7].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Problems

How can I identify if my optimization problem is stuck on a local optimum?

Symptoms:

- Small variations in expression levels don't improve production

- Different random seeds in your algorithm converge to different solutions

- Literature reports significantly higher titers for similar pathways

Solutions:

- Increase initial diversity: Start with a more diverse population of expression variants

- Implement "gap" exploration: Use algorithms like B-NTGA that specifically target unexplored regions of the fitness landscape [7]

- Temporarily allow worse solutions: Simulated annealing approaches can help escape local optima

- Try different promoter strengths: Use predefined promoter sets spanning wide expression ranges [8] [1]

Why does my pathway optimization show high intermediate metabolite accumulation?

Diagnosis: This indicates flux imbalance—some enzymes are overactive while others are bottlenecks [1].

Resolution strategies:

Table: Troubleshooting Flux Imbalance Issues

| Observation | Likely Cause | Experimental Fix |

|---|---|---|

| Early pathway intermediates accumulate | Downstream enzymes too slow | Increase expression of downstream enzymes |

| Toxic intermediates affect growth | Enzyme expression too high | Systematically reduce expression of early pathway enzymes |

| Final product yield fluctuates with minor changes | Rugged fitness landscape with many local optima | Sample larger combinatorial space with predictive modeling [1] |

| Different clones show extreme variation in productivity | Landscape has steep peaks and valleys | Use regression modeling to predict optimal combinations from sparse sampling [1] |

What do I do when my combinatorial library is too large to screen?

Problem: Analytical methods like HPLC or GC-MS have throughput limitations that prevent exhaustive testing of large combinatorial libraries [1].

Proven approaches:

- Sparse sampling: Randomly sample 1-5% of the library and use regression modeling to predict optimal combinations [1]

- UTR Library Designer: Algorithmically design a minimal library covering the desired expression space [8]

- Hierarchical screening: Use rapid preliminary screens (e.g., colorimetric) to identify promising regions before detailed analysis

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Predictive combinatorial design using UTR Library Designer

This method enables systematic optimization of gene expression levels while minimizing the number of variants needed [8].

Workflow Overview:

Materials Required:

Table: Essential Research Reagents

| Reagent | Function | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Promoter Set | Provides expression variation | Constitutive promoters spanning >10,000-fold range [1] |

| UTR Library | Fine-tunes translation efficiency | Designed sequences covering target ΔGUTR values [8] |

| Reporter Genes | Validates expression predictions | GFP, RFP for rapid quantification [8] |

| Assembly System | Constructs combinatorial libraries | Gibson assembly, Golden Gate, or standardized vector systems [1] |

| Selection Markers | Maintains plasmid stability | Antibiotic resistance or auxotrophic markers [1] |

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Define target expression range - Determine minimum and maximum expression levels needed for each gene

- Calculate thermodynamic parameters - Use the energy model ΔGUTR (difference in Gibbs free energy before and after 30S ribosomal complex assembly) [8]

- Generate sequence variants - Apply genetic algorithm to find 5'-UTR sequences that achieve desired expression levels

- Validate with reporter genes - Test a subset of designs with fluorescent proteins to verify correlation between predicted and actual expression

- Build pathway library - Assemble selected UTR variants with your pathway genes

- Screen for performance - Analyze library members for product formation using available assays

Key Computational Parameters:

- ΔGUTR calculation considers ribosome binding affinity and mRNA accessibility

- Genetic algorithm uses fitness function based on difference between desired and predicted expression

- Typically achieves 5,000-fold expression changes with 16 intermediates [8]

Protocol: Regression modeling for pathway optimization with limited screening

This approach enables optimization of large combinatorial spaces with minimal experimental measurements [1].

Workflow Overview:

Implementation Details:

- Library construction - Create full combinatorial library using standardized assembly methods [1]

- Sparse sampling - Randomly select 1-3% of the total library for testing

- Analytical measurement - Quantify product titers using HPLC, GC-MS, or other relevant methods

- Model training - Use linear regression to relate genotype (promoter/UTR combinations) to phenotype (titer)

- Prediction and validation - Test model-predicted high performers beyond the training set

Case Study Success:

- Applied to 5-enzyme violacein biosynthetic pathway in yeast

- Successfully predicted genotypes that preferentially produced each of the pathway's four primary products

- Achieved optimization with only 3% library sampling [1]

Computational & Algorithmic Solutions

Which algorithms are most effective for navigating fitness landscapes?

For rugged landscapes with local optima:

- Balanced Non-dominated Tournament Genetic Algorithm (B-NTGA) - Actively explores "gaps" in Pareto front approximation [7]

- NTGA2 - Uses phenotype distance between individuals to improve evolution process [7]

- U-NSGA-III and θ-DEA - Effective for many-objective optimization [7]

Key algorithm selection criteria:

- Number of objectives (2-5 for typical metabolic pathways)

- Computational resources available

- Need for constraint handling (e.g., metabolite toxicity, growth requirements)

How do I implement fitness "seascapes" for dynamic optimization?

Fitness seascapes extend the landscape concept for changing environments where optimal solutions shift over time [5].

Applications in metabolic engineering:

- Long-term cultivation - Selection pressures change as strains evolve

- Scale-up processes - Bioreactor conditions differ from initial screens

- Drug cycling - Microbial systems adapt to periodic stress [5]

Implementation strategy:

- Model environmental changes as temporal shifts in the adaptive topography

- Use algorithms that maintain diversity to accommodate changing optima

- Consider time-varying selective conditions in experimental design

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I avoid NP-hard complexity in pathway optimization?

No, but you can manage it effectively. While the theoretical problem remains NP-hard, practical approaches include:

- Reducing solution space - Use biological knowledge to constrain reasonable expression ranges

- Dimension reduction - Identify and focus on the most influential enzymes

- Smarter sampling - Apply design-of-experiments principles rather than exhaustive testing

- Divide and conquer - Optimize sub-pathways separately before combining

How many variants should I test for a 5-gene pathway?

Practical guidance based on successful studies:

Table: Recommended Library Sizes for Pathway Optimization

| Screening Capacity | Recommended Approach | Typical Library Size | Success Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (<100 clones) | Fractional factorial design | 50-100 variants | Focus on most important variables |

| Medium (100-1000 clones) | Sparse sampling with modeling | 1-5% of total space | Violacein pathway [1] |

| High (>1000 clones) | Full combinatorial + selection | Thousands of variants | Growth-coupled phenotypes [1] |

What evidence exists that fitness landscapes for metabolic pathways are rugged?

Multiple empirical studies confirm ruggedness:

- Taxadiene production in E. coli - Landscape analysis showed local optima that would trap sequential optimization [1]

- Xylose fermentation in S. cerevisiae - Optimal expression combinations were non-intuitive [1]

- Violacein biosynthesis - Branched pathway structure created complex expression-titer relationships [1]

This empirical evidence justifies using global optimization algorithms rather than simple hill-climbing approaches.

Maximizing Titer, Yield, and Selectivity in Branched Pathways

For researchers and scientists in drug development, optimizing branched enzymatic pathways presents a significant challenge. Balancing the expression levels of multiple enzymes to maximize the production of a desired compound requires precise control over complex biological systems. Combinatorial optimization strategies have emerged as powerful tools to navigate this high-dimensional problem efficiently, enabling the simultaneous tuning of multiple variables without requiring prior knowledge of the optimal configuration. This technical support center provides actionable troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help you overcome common obstacles in your pathway optimization experiments.

Troubleshooting Guides

Q: Despite high individual enzyme activities in assays, my overall pathway titer remains low. What could be causing this?

A: This common issue often stems from an imbalance in enzyme expression levels, creating rate-limiting steps and metabolic bottlenecks.

Check for Expression Imbalances

- Protocol: Use quantitative proteomics (e.g., LC-MS/MS) to measure the actual cellular concentrations of each pathway enzyme. Alternatively, employ enzyme-fusion fluorescent tags for relative quantification via flow cytometry.

- Acceptable Range: Aim for a coefficient of variation (CV) of ≤15% between expected and measured expression levels. Significant deviations indicate problematic imbalances.

- Solution: Implement combinatorial optimization methods like COMPASS or VEGAS that allow simultaneous tuning of multiple enzyme expression levels rather than sequential adjustment [9].

Assess Metabolic Burden

- Protocol: Compare growth curves (OD600) of your production strain against an empty vector control. A significant growth defect indicates excessive metabolic burden.

- Solution: Switch from plasmid-based to chromosome-integrated expression systems. Use inducible promoters or dynamic regulation to delay enzyme production until after the growth phase [9].

Evaluate Cofactor and Precursor Availability

- Protocol: Measure intracellular concentrations of key cofactors (NADPH, ATP) and pathway precursors. Use enzymatic assays or LC-MS methods.

- Solution: Introduce or upregulate genes involved in cofactor regeneration. Consider engineering substrate uptake systems to improve precursor availability.

Problem 2: Poor Product Selectivity in Branched Pathways

Q: My pathway produces significant amounts of undesired byproducts due to competing enzymatic reactions. How can I improve selectivity?

A: This occurs when pathway enzymes have substrate promiscuity or when native host metabolism diverts intermediates.

Characterize Enzyme Specificity

- Protocol: Express each pathway enzyme individually and test activity against both target and non-target substrates using in vitro enzyme assays with HPLC or MS detection.

- Solution: Employ enzyme engineering approaches such as directed evolution or computational design to enhance enzyme specificity [10]. Machine-learning guided engineering has shown 1.6- to 42-fold improvements in desired activity [11].

Apply Spatial Organization

- Protocol: Fuse competing enzymes to synthetic scaffolds with tunable interaction domains. Test varying scaffold:enzyme stoichiometries (e.g., 0.5:1 to 5:1).

- Solution: Create enzyme complexes that channel intermediates between active sites, reducing access to competing enzymes.

Implement Dynamic Regulation

- Protocol: Place competing enzyme genes under the control of biosensors that respond to your desired product or key intermediates.

- Solution: Use CRISPRi or small RNA-based regulators to dynamically downregulate competing pathway enzymes when undesired byproducts accumulate [9].

Problem 3: Unstable Strain Performance During Scale-up

Q: My optimized strain performs well in lab-scale bioreactors but shows performance deterioration during scale-up. How can I improve genetic stability?

A: This typically results from genetic instability of expression systems or insufficient robustness to changing environmental conditions.

Verify Genetic Stability

- Protocol: Passage your production strain for 50+ generations in non-selective media, periodically measuring plasmid retention (for plasmid-based systems) and production capacity.

- Solution: For plasmid-based systems, use high-stability origins and selection markers. Consider switching to genomic integration approaches, which provide more stable expression [12].

Profile Environmental Response

- Protocol: Test production across a range of pH (±0.5 from optimum), temperature (±2°C from optimum), and dissolved oxygen (±10% from setpoint) conditions in controlled bioreactors.

- Solution: Isolate environmental stress-responsive promoters from your host chassis and use them to drive expression of the most sensitive pathway enzymes, creating built-in compensation for environmental fluctuations.

Employ Robust Optimization Strategies

- Protocol: During strain development, include fluctuating environmental conditions in your screening process rather than only optimizing for ideal conditions.

- Solution: Use multi-objective optimization algorithms that simultaneously maximize titer, yield, and stability metrics [13].

Advanced Optimization Methodologies

Combinatorial Optimization Strategies

Combinatorial optimization allows multivariate testing of pathway configurations without requiring prior knowledge of optimal expression levels [9]. The table below compares key methodologies:

Table 1: Combinatorial Optimization Methods for Enzyme Pathway Engineering

| Method | Key Features | Throughput | Best For | Experimental Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COMPASS [9] | Integration of multiple gene modules into genomic loci | High | Complex pathways with 5+ enzymes; metabolic engineering | CRISPR/Cas editing capabilities; library sequencing |

| VEGAS [9] | In vivo assembly of pathway variants | Medium | Rapid prototyping; 3-5 enzyme pathways | Specialized yeast strain; flow cytometry |

| Machine-Learning Guided [11] | Predictive modeling from sequence-function data | Very high (10,000+ variants) | Enzyme engineering; hotspot identification | Cell-free expression system; automation |

| MAGE | Multiplex automated genome engineering | High | Genomic modifications; regulatory elements | Specialized equipment; oligonucleotide synthesis |

| Combinatorial Promoter/RBS Libraries | Systematic variation of expression parts | Medium | Fine-tuning expression levels; 2-3 enzyme pathways | Fluorescent reporters; FACS capability |

Machine Learning-Enhanced Engineering

Recent advances integrate high-throughput experimentation with machine learning to dramatically accelerate enzyme engineering:

- Platform Components: ML-guided platforms combine cell-free DNA assembly, cell-free gene expression, and functional assays to rapidly map fitness landscapes [11].

- Workflow:

- Generate sequence-function data for single-order mutations

- Train supervised ridge regression ML models

- Predict higher-order mutants with enhanced activity

- Performance: This approach has demonstrated 1.6- to 42-fold activity improvements for amide synthetase variants [11].

Computational Enzyme Design

Fully computational workflows now enable design of efficient enzymes without extensive experimental optimization:

- TIM-barrel Framework: Designing within stable, natural protein folds like TIM-barrels provides optimal scaffolding for new enzymatic functions [14].

- Workflow: Combinatorial backbone assembly followed by active-site design using atomistic energy calculations.

- Performance: This approach has generated Kemp eliminases with catalytic efficiencies of 12,700 Mâ»Â¹sâ»Â¹, surpassing previous computational designs by two orders of magnitude [14].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Enzyme Variant Screening Using Cell-Free Expression

Adapted from Nature Communications 16, 865 (2025) [11]

Purpose: Rapidly generate and test sequence-defined enzyme variant libraries.

Materials:

- Cell-free protein expression system (e.g., PURExpress)

- DNA primers for site-saturation mutagenesis

- DpnI restriction enzyme

- Gibson assembly mix

- PCR reagents and thermocycler

- Microplate reader or HPLC-MS for activity assays

Procedure:

- Design Primers: Create forward and reverse primers containing desired mutations with 18-25 bp homology arms.

- PCR Amplification: Amplify plasmid DNA using mutagenic primers (98°C for 30s, 25 cycles of 98°C for 10s, 55°C for 20s, 72°C for 4 min/kb).

- Digest Template: Add 1μL DpnI to 20μL PCR product, incubate at 37°C for 1 hour to digest methylated parent plasmid.

- Gibson Assembly: Combine 50ng digested PCR product with 2× Gibson assembly master mix, incubate at 50°C for 1 hour.

- Linear DNA Template Preparation: Amplify expression templates from assembled plasmid (98°C for 30s, 15 cycles of 98°C for 10s, 60°C for 20s, 72°C for 3 min/kb).

- Cell-Free Expression: Combine 2μL linear DNA template with 8μL cell-free expression mix, incubate at 30°C for 4-6 hours.

- Activity Screening: Directly assay enzyme activity in the cell-free reaction mixture using appropriate substrates.

Technical Notes:

- This workflow enables testing of 1000+ variants within 2-3 days

- Include positive and negative controls in each screening plate

- Optimize DNA template concentration for each enzyme (typically 5-20nM final)

Protocol 2: Multi-Module Pathway Integration Using COMPASS

Adapted from Nature Communications 11, 2446 (2020) [9]

Purpose: Generate combinatorial diversity in multi-enzyme pathway expression levels.

Materials:

- Library of regulatory parts (promoters, RBS)

- CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing system

- Homology-directed repair template DNA

- Electroporation equipment

- Selection antibiotics

Procedure:

- Module Design: Design gene modules with varied regulatory parts controlling each pathway enzyme.

- In Vitro Assembly: Assemble modules using Golden Gate or Gibson assembly with terminal homology regions.

- Library Amplification: Transform assembled constructs into E. coli for amplification, pool colonies for max diversity.

- CRISPR/Cas Integration: Design gRNAs targeting specific genomic loci, co-transform with repair templates containing module libraries.

- Selection and Screening: Plate on selective media, screen for production using biosensors or analytical methods.

- Hit Validation: Sequence validated hits to identify optimal regulatory part combinations.

Technical Notes:

- Target 3-5 genomic loci with neutral or beneficial effects on production

- Include 500-1000bp homology arms for efficient integration

- Screen 1000+ colonies to adequately sample combinatorial space

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Combinatorial Pathway Optimization

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | pET series, pRSFDuet | Recombinant protein expression in microbial hosts | Copy number, compatibility, selection marker [15] |

| Cell-Free Systems | PURExpress, homemade extracts | Rapid protein synthesis without living cells | Yield, cost, compatibility with difficult proteins [11] |

| Regulatory Parts | Promoter libraries, RBS collections | Fine-tuning enzyme expression levels | Strength range, orthogonality [9] |

| Genome Editing | CRISPR/Cas9, λ-Red recombinering | Stable genomic integration of pathway modules | Efficiency, host range, off-target effects [9] |

| Biosensors | Transcription factor-based, riboswitches | High-throughput screening of production strains | Dynamic range, specificity, response time [9] |

| Computational Tools | Rosetta, PROSS, FuncLib | Enzyme design and stability optimization | Accuracy, computational requirements [14] |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How many variants should I screen for effective combinatorial optimization? A: This depends on your library complexity. For promoter/RBS libraries with 3-5 enzymes, screening 1000-5000 variants is typically sufficient. For enzyme engineering with larger sequence spaces, ML-guided approaches can reduce screening burden by 10-100 fold [11].

Q: What host organism is best for branched pathway expression? A: E. coli remains the most common host for recombinant enzyme production due to rapid growth, well-characterized genetics, and high protein expression capabilities [15]. However, consider yeast or specialized strains for complex eukaryotic enzymes or post-translational modifications.

Q: How can I predict which enzyme in my pathway is rate-limiting? A: Use metabolic flux analysis by measuring intermediate accumulation, or employ ({}^{13}C) metabolic flux analysis. Computational modeling using kinetic parameters can also identify potential bottlenecks before experimental testing.

Q: What metrics are most important for scaling optimized strains? A: While titer (g/L) is commonly emphasized, productivity (g/L/h) and yield (g product/g substrate) are often more economically significant. Stability metrics like plasmid retention or production consistency over 50+ generations are critical for industrial applications [12].

Q: Can I combine combinatorial optimization with traditional DOE methods? A: Yes, sequential approaches often work well: use combinatorial methods for initial broad exploration of design space, followed by DOE for fine-tuning around promising hits.

Successfully maximizing titer, yield, and selectivity in branched pathways requires integrated strategies combining combinatorial optimization, advanced computational design, and robust experimental protocols. By addressing common troubleshooting scenarios systematically and leveraging the latest methodologies in enzyme engineering and pathway optimization, researchers can dramatically improve both the efficiency and success rate of their biocatalyst development projects.

The Critical Role of Promoter Systems in Controlling Relative Enzyme Expression

Promoters are DNA sequences where transcription of a gene begins, serving as the primary on/switch and control point for gene expression by directing RNA polymerase to the correct initiation site [16] [17]. In metabolic engineering, precisely controlling the relative expression levels of multiple enzymes is a fundamental challenge. Imbalanced expression can overburden the host cell, lead to toxic intermediate accumulation, and dramatically reduce product titers [1]. Combinatorial optimization using promoter libraries provides a powerful solution, enabling researchers to systematically explore a vast expression space to find the optimal balance for a pathway [1]. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance for implementing these strategies effectively.

FAQs: Core Concepts of Promoter Systems

1. What is the fundamental difference between RNA Polymerase II and RNA Polymerase III promoters?

The key distinction lies in the type of RNA they transcribe. RNA Polymerase II (Pol II) promoters primarily drive the expression of messenger RNA (mRNA) that codes for proteins. In contrast, RNA Polymerase III (Pol III) promoters transcribe small, non-coding RNAs, such as transfer RNA (tRNA), 5S ribosomal RNA, and the U6 small nuclear RNA (snRNA) [18] [16]. This makes Pol III promoters, like U6 and U3, particularly valuable in technologies like CRISPR/Cas9 for expressing short guide RNAs (sgRNAs) [18].

2. How do bacterial and eukaryotic promoters differ in their structure?

Bacterial and eukaryotic promoters have distinct architectures. In bacteria, consensus sequences at the -10 (Pribnow box, TATAAT) and -35 (TTGACA) positions relative to the transcription start site are recognized by RNA polymerase complexed with a sigma factor [16] [17].

Eukaryotic promoters are more complex and can be divided into three regions [16] [17]:

- Core Promoter: Located immediately upstream of the gene, it includes the RNA polymerase binding site, the TATA box, and the transcription start site (TSS).

- Proximal Promoter: Found within approximately 250 base pairs upstream of the TSS, it contains primary regulatory elements.

- Distal Promoter: Located further upstream, it contains additional regulatory elements like enhancers, which can loop back to interact with the core promoter.

3. What are the advantages of using a combinatorial promoter library for metabolic pathway optimization?

Traditional iterative tuning of enzyme expression is time-consuming and can miss optimal combinations due to complex, non-linear interactions (epistasis) between genes [1]. Combinatorial promoter libraries allow you to:

- Explore Multi-Dimensional Space: Simultaneously vary the expression of all pathway enzymes.

- Uncover Global Optima: Identify synergistic expression combinations that iterative methods might miss.

- Reduce Development Time: Test a wide spectrum of expression levels in a single, parallel experiment [1].

4. What are the common types of promoters used in expression vectors?

The table below summarizes common promoters used in various host organisms [16]:

| Promoter | Expression Type | Host | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| T7 | Constitutive | Bacteriophage/Bacterial | Requires T7 RNA polymerase; very strong. |

| lac | Constitutive/Inducible | Bacterial | From Lac operon; can be induced by IPTG. |

| CMV | Constitutive | Mammalian | Strong promoter from human cytomegalovirus. |

| U6 | Constitutive | Mammalian | Pol III promoter for small RNA expression. |

| CAG | Constitutive | Mammalian | Strong hybrid promoter. |

| CaMV35S | Constitutive | Plant | From Cauliflower Mosaic Virus. |

| GDS | Constitutive | Yeast | Strong promoter from glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. |

| TRE | Inducible | Multiple | Tetracycline response element promoter. |

5. How can I reduce "leaky" expression from an inducible promoter in yeast?

Significant leakiness in yeast inducible synthetic promoters (iSynPs) is often caused by cryptic transcriptional activation from upstream sequences. To minimize this [19]:

- Insert Insulators: Place a >1-kbp insulating DNA sequence (e.g., the KpARG4 sequence in Komagataella phaffii) upstream of the promoter to block spurious activation.

- Optimize Operator Placement: Fuse the operator sequence directly upstream of the TATA box with minimal spacing (e.g., ≤40 bp).

- Screen Operator Variants: Mutate the operator sequence to reduce its inherent cryptic activation without compromising its binding to the synthetic transcription activator.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low or No Expression of Target Enzyme

Possible Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Weak or Incompatible Promoter

- Solution: Verify that the promoter is appropriate for your host organism (see Table above). For example, a mammalian CMV promoter will not function in E. coli. Consider switching to a stronger or host-specific promoter [16] [20].

- Solution: For metabolic pathways, consider using a validated constitutive promoter set with known relative strengths to ensure sufficient expression [1].

Cause: Incorrect Genetic Construct

- Solution: Confirm the promoter sequence and its orientation. Ensure the gene is cloned downstream of the promoter in the correct reading frame. Sequence the entire expression cassette to rule out mutations.

Cause: Cell Health Burden

- Solution: High-level expression of a heterologous enzyme can be toxic to the host. Lower the incubation temperature or use an inducible system to decouple growth from protein production [19].

Problem 2: Imbalanced Metabolic Pathway Leading to Low Product Titer

Possible Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Rate-Limiting Step Undetected

- Solution: Implement a combinatorial promoter library. This approach allows you to systemically vary the expression of each enzyme in the pathway to identify the optimal balance that maximizes flux toward the desired product and minimizes intermediate accumulation [1].

Cause: Insufficient Screening Throughput

- Solution: If your product lacks a high-throughput assay (e.g., color), use a sparse-sampling strategy. A regression model can be trained on a randomly selected subset (e.g., 3%) of the total library. This model can then predict high-performing genotypes for validation, drastically reducing the number of clones that need to be analyzed with low-throughput methods like HPLC or GC-MS [1].

Protocol: Combinatorial Pathway Balancing with Sparse Sampling [1]

- Design and Build: Select a set of promoters with a range of strengths for each gene in your pathway. Use standardized assembly (e.g., Gibson assembly, Golden Gate) to construct a combinatorial library of pathway variants.

- Transform and Plate: Transform the library into your production host and plate on selective media.

- Random Sampling: Pick a random subset of colonies (e.g., 1-5% of the total library diversity) and inoculate them into deep-well blocks for cultivation.

- Phenotype Measurement: Grow cultures and measure the product titer using your analytical method (e.g., HPLC, LC-MS).

- Model Training: Genotype each sampled variant (e.g., by sequencing) and use the genotype-phenotype data to train a linear regression model.

- Prediction and Validation: Use the trained model to predict high-performing genotypes from the unsampled portion of the library. Construct and test these top predictions to validate the model and identify your best-producing strain.

Problem 3: High Leaky Expression in Inducible Systems

Possible Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Cryptic Upstream Activation (Especially in Yeasts)

- Solution: Insert a long (>1 kbp) insulating DNA fragment upstream of your synthetic promoter to block activation from endogenous transcription factors [19].

- Solution: Re-design the promoter architecture by moving the operator closer to the TATA box and screening for operator mutants with lower background activity [19].

Cause: Incomplete Repression

- Solution: Ensure the repressor protein is expressed at sufficient levels. For systems like the lac promoter in E. coli, use a strain that overproduces the LacI repressor (e.g., lacIq allele) [16].

Experimental Workflows and Pathways

Diagram: Workflow for Machine-Learning-Guided Enzyme Engineering

This workflow illustrates an integrated platform that combines cell-free expression with machine learning to accelerate enzyme engineering. Key steps include using cell-free systems to rapidly generate sequence-function data for hundreds of variants, which is then used to train a machine learning model. The model predicts superior performers, creating an efficient design-build-test-learn cycle [21].

Diagram: Combinatorial Optimization of a Multi-Gene Pathway

This diagram shows the process of balancing a multi-enzyme pathway. A library is created by combining different promoters from a strength-graded pool for each gene. A small, random sample is phenotyped, and the data trains a regression model to predict the best-performing combination in the full library, avoiding the need to screen every variant [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Constitutive Promoter Set | A set of well-characterized promoters with varying strengths for a specific host. | Creating combinatorial libraries for metabolic pathway balancing in S. cerevisiae [1]. |

| RNA Pol III Promoter (e.g., U6) | Drives high-level expression of small, non-coding RNAs. | Expressing guide RNAs (gRNAs) in CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing systems [18] [16]. |

| Inducible Promoter System | Allows precise temporal control of gene expression using an inducer molecule (e.g., DAPG, Dox). | Decoupling cell growth from protein production to express toxic proteins [19]. |

| Broad-Host-Range Promoter | Functions across different species or genera. | Testing gene expression in multiple potential host strains without constructing species-specific vectors [20]. |

| Cell-Free Gene Expression (CFE) System | A transcription-translation system without intact cells. | Rapidly screening large mutant enzyme libraries in a high-throughput manner [21]. |

| Insulator Sequences | DNA elements that block enhancer-promoter interactions. | Reducing leaky expression in synthetic inducible promoters in yeast [19]. |

| Standardized Assembly Method | A standardized DNA assembly method (e.g., Gibson, Golden Gate). | Efficient and reliable construction of multi-gene pathways and promoter libraries [1]. |

| Apoptosis inducer 13 | Apoptosis inducer 13, MF:C60H59ClF6N8O4PRu, MW:1237.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Tmv-IN-7 | Tmv-IN-7, MF:C17H15ClN6OS, MW:386.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Methodologies in Action: Building Libraries and Deploying Computational Models

Constructing Combinatorial Promoter and Gene Library Platforms

Combinatorial promoter and gene library platforms are indispensable tools in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering for optimizing complex biological systems. These platforms enable researchers to systematically explore vast genetic design spaces without prior knowledge of the optimal combination of individual genetic elements, such as promoters, coding sequences, or terminators [22]. In the context of enzyme expression level optimization, this approach allows for the fine-tuning of multiple genes within a biosynthetic pathway simultaneously, overcoming the limitations of traditional sequential optimization methods that are often time-consuming and likely to miss optimal configurations due to complex, non-linear biological interactions [22]. The fundamental principle involves generating diverse genetic variants through methodical assembly techniques and screening the resulting libraries to identify clones with enhanced performance characteristics, such as improved enzyme activity, stability, or production titers [23] [24].

Key Experimental Platforms and Methodologies

rmCombi-OGAB for Directed Evolution

The rmCombi-OGAB (random mutagenesis with Combinatorial Ordered Gene Assembly in Bacillus subtilis) platform combines random mutagenesis with combinatorial DNA assembly to evolve biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs). This method is particularly valuable for optimizing antibiotic production, as demonstrated with Gramicidin S, where it achieved a 1.5-fold improvement in productivity [23].

Experimental Protocol:

- Random Mutagenesis: Subject target gene clusters to error-prone PCR (epPCR) to introduce random mutations. For a 22 kb plasmid, divide it into four fragments of approximately 5.5 kb for mutagenesis [23].

- Combinatorial Assembly: Design fragment ends with AarI or SfiI restriction enzyme recognition sequences. Digest fragments with these enzymes to create defined sticky ends that control ligation order [23].

- Transformation and Assembly: Transform the digested fragments into a suitable host strain (e.g., B. subtilis BUSY9797 carrying the pUB8 plasmid for non-ribosomal peptide activation) where they are assembled in vivo into mutated plasmids [23].

- Screening Cycles: Screen transformants for productivity (e.g., antibiotic yield). Select top producers, mix their plasmids, and repeat the digestion and assembly process for 2-3 cycles to enrich beneficial combinations [23].

GEMbLeR for Promoter and Terminator Shuffling

GEMbLeR (Gene Expression Modification by LoxPsym-Cre Recombination) is a yeast-based platform that enables in vivo, multiplexed shuffling of promoter and terminator modules. This system can generate strain libraries where expression of each pathway gene varies over 120-fold, allowing rapid balancing of biosynthetic pathways [24].

Experimental Protocol:

- Construct GEM Modules: Replace native promoter and terminator of target genes with 5' and 3' Gene Expression Modulator (GEM) arrays. These arrays contain libraries of upstream promoter elements (UPEs) or terminator sequences, separated by orthogonal LoxPsym recombination sites [24].

- Induce Recombination: Introduce Cre recombinase to trigger recombination between LoxPsym sites. This causes deletion, inversion, translocation, and duplication of GEM-blocks, creating vast diversity in expression profiles from a single starting strain [24].

- Screen for Performance: Screen the resulting library for desired phenotypes, such as increased product titers. When applied to the astaxanthin biosynthesis pathway, a single round of GEMbLeR doubled production titers [24].

Model-Guided Combinatorial Library Construction

This approach combines genome-scale models (GSMs) and machine learning with combinatorial library construction to optimize complex metabolic pathways, such as tryptophan biosynthesis in yeast [25].

Experimental Protocol:

- Target Identification: Use constraint-based modeling with GSMs to identify gene targets that influence metabolic flux toward the desired product. Key targets for aromatic amino acid biosynthesis include CDC19, TKL1, TAL1, PCK1, and PFK1 [25].

- Promoter Mining: Mine transcriptomics data to select a diverse set of promoters (e.g., 25 sequence-diverse promoters plus 5 native promoters) with a wide range of activities [25].

- One-Pot Library Assembly: Create a platform strain with deleted or knocked-down target genes. Use high-fidelity homologous recombination and CRISPR/Cas9 genome engineering to assemble a library of expression cassettes (e.g., 7776 possible combinations) at a defined genomic locus in a single transformation step [25].

- Screening and Model Training: Employ high-throughput biosensors to screen library variants. Use the resulting data to train machine learning models that predict optimal genetic designs, potentially improving tryptophan titer by up to 74% compared to the best designs used for training [25].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Library Design and Construction

Q1: Our combinatorial library shows extremely low transformation efficiency during assembly. What could be the cause?

- Cause A: Excessive homology between genetic parts. Repeated use of similar regulatory elements can cause homologous recombination in the host, leading to plasmid instability or incorrect assembly [25].

- Solution: Select sequence-diverse parts during the initial design phase. In silico analysis of homology between all intended parts before synthesis is recommended.

- Cause B: Overly large DNA fragments or too many simultaneous assembly fragments. This can overwhelm the host's recombination machinery [25].

- Solution: For complex libraries, consider a hierarchical assembly strategy or optimize the host strain to enhance recombination efficiency (e.g., using specific E. coli or yeast recombination-deficient strains for plasmid propagation).

Q2: The final library complexity is much lower than theoretically designed. How can we improve this?

- Cause A: Inefficient ligation or recombination. This results in a high proportion of empty vectors or incorrectly assembled constructs.

- Solution: Optimize the molar ratios of DNA fragments during assembly. For Golden Gate or other restriction-ligation based methods, ensure complete digestion and use high-fidelity enzymes. For in vivo assembly, maximize transformation efficiency [25].

- Cause B: Toxicity of certain genetic combinations. Some constructs may be lethal to the host cells, preventing their recovery in the library.

- Solution: Use tightly regulated or inducible systems for gene expression during the initial cloning stages. Consider using a host strain with a lower transformation background to better detect toxic effects.

Screening and Analysis

Q3: During screening, we observe a high number of non-producers or clones with no detectable expression. What steps should we take?

- Cause A: High mutation rates from random mutagenesis. Error-prone PCR can introduce deleterious mutations, including frameshifts or stop codons [23].

- Solution: Control the mutation rate by adjusting Mg²⺠or Mn²⺠concentrations in the epPCR reaction. Sequence a sample of non-producing clones to determine the average mutation rate; a rate of approximately 0.77 substitutions/kb has been successfully used [23].

- Cause B: Improper part assembly or integration failure.

- Solution: Implement rigorous quality control (QC) checks. Use colony PCR and diagnostic restriction digests on a random subset of clones to verify correct assembly before proceeding to large-scale screening.

Q4: Our screening results show poor correlation between model predictions and experimental data. How can we resolve this?

- Cause A: Inadequate training data for the machine learning model. The initial dataset may not cover the biological design space sufficiently [25].

- Solution: Ensure the combinatorial library is well-characterized and covers a wide range of expression levels. Include the native promoters and a null control in the screening to establish a baseline.

- Cause B: Unaccounted-for biological complexity. Post-transcriptional/translational regulation, metabolic burden, or unknown host-pathway interactions can affect outcomes.

- Solution: Incorporate additional data layers into the model, such as proteomics or metabolomics data. Use mechanistic models (e.g., GSMs) to inform the initial library design and identify potential bottlenecks [25].

Platform-Specific Issues

Q5: In the GEMbLeR system, we notice reduced gene expression after inserting LoxPsym sites. Is this expected?

- Answer: Yes, this is a known design constraint. Inserting LoxPsym sites in the 5' untranslated region (UTR) can significantly reduce protein expression, potentially by forming inhibitory mRNA secondary structures that hinder translation, without necessarily reducing mRNA levels [24].

- Solution: Position the LoxPsym site upstream of the transcription start site (TSS) rather than closer to the start codon. This minimizes the impact on translation while still allowing for Cre-mediated recombination [24].

Q6: When using rmCombi-OGAB, how do we determine when to stop the screening cycles?

- Answer: The screening cycles can be concluded when subsequent rounds no longer yield significant improvements in the target productivity metric [23].

- Solution: In the Gramicidin S study, screening was stopped at the third cycle because no clones showed higher productivity than the top producer from the second cycle. Always include your original starting strain as an internal standard in every screening cycle for benchmarking [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key reagents and resources for constructing combinatorial libraries.

| Item | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal LoxPsym Sites | Enable independent, parallel recombination of DNA modules without cross-talk. | GEMbLeR system for promoter/terminator shuffling in yeast [24]. |

| Error-Prone PCR (epPCR) Kit | Introduces random mutations into DNA sequences to expand diversity beyond designed libraries. | rmCombi-OGAB for directed evolution of biosynthetic gene clusters [23]. |

| Type IIS Restriction Enzymes (e.g., AarI, SfiI) | Cut DNA outside their recognition sequence, creating unique sticky ends for scarless, ordered assembly of multiple fragments. | Defining ligation order in Combi-OGAB and other combinatorial assemblies [23]. |

| Barcoded Sequencing Library | Allows for multiplexed tracking of library variants via NGS, linking genotype to phenotype in pooled screens. | PERSIST-seq for high-throughput analysis of mRNA stability and translation [26]. |

| Genome-Scale Model (GSM) | Computational metabolic network used to pinpoint key engineering targets and predict flux changes. | Identifying gene targets (CDC19, TKL1) for tryptophan pathway optimization [25]. |

| Biosensor Systems | Genetically encoded devices that transduce metabolite concentration into a detectable signal (e.g., fluorescence). | High-throughput screening of tryptophan-producing yeast libraries [25]. |

| HDAC ligand-1 | HDAC ligand-1, MF:C7H8N2O, MW:136.15 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| G|Aq/11 protein-IN-1 | G|Aq/11 protein-IN-1, MF:C19H27N5, MW:325.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow Visualization

Combinatorial Library Construction and Screening Workflow

rmCombi-OGAB Directed Evolution Cycle

Data Presentation: Quantitative Outcomes from Combinatorial Optimization

Table: Performance improvements achieved through combinatorial optimization strategies.

| Platform/System | Target Product | Key Performance Improvement | Key Metric | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rmCombi-OGAB | Gramicidin S (Antibiotic) | 1.5-fold productivity increase | Final Titer | [23] |

| GEMbLeR | Astaxanthin (Antioxidant) | 2-fold increase in production titer | Final Titer | [24] |

| Model-Guided + ML | Tryptophan (Amino Acid) | Up to 74% higher titer vs. training set best | Final Titer | [25] |

| Promoter Library (E. coli) | GFP (Reporter) | Activity range from 21.79 to 7606.83 RFU/OD·ml | Promoter Strength | [27] |

| PERSIST-seq (mRNA) | Nanoluc Luciferase (Reporter) | Simultaneous improvement of stability & expression | mRNA Stability & Protein Output | [26] |

Regression Modeling for Predictive Optimization from Sparse Data

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Common Experimental Hurdles

Problem: Inaccurate Model Predictions with New Enzyme Variants My model performs well on training data but generalizes poorly to new, unseen enzyme variants. What could be wrong?

Answer: This is often caused by a dataset that does not adequately represent the vastness of protein sequence space. The model is likely overfitting to the limited examples in your sparse data.

- Root Cause: The sequence-function data used for training lacks sufficient diversity, or the model has been trained on a region of sequence space that is not relevant to the new variants you are testing.

- Solution: Ensure your initial combinatorial library is designed to cover a wide and representative range of mutations. As highlighted in one study, exploring fitness landscapes across multiple regions of sequence space is crucial for building models capable of forward design [21]. If possible, augment your training data with evolutionary zero-shot fitness predictors, which can provide a valuable prior and improve model generalization [21].

Problem: Efficiently Generating Large Sequence-Function Datasets Generating high-quality sequence-function data is slow and resource-intensive. How can I create the large datasets needed for robust regression modeling more efficiently?

Answer: Adopt integrated high-throughput platforms that combine rapid cell-free protein synthesis with functional assays.

- Solution: Implement a cell-free DNA assembly and gene expression workflow. This approach allows for the rapid synthesis and testing of thousands of sequence-defined protein mutants in a matter of days, bypassing the need for laborious transformation and cloning steps in living cells [21]. One proven methodology involves:

- Using PCR with primers containing nucleotide mismatches to introduce desired mutations.

- Digesting the parent plasmid with DpnI.

- Forming a mutated plasmid via intramolecular Gibson assembly.

- Amplifying linear DNA expression templates (LETs) with a second PCR.

- Expressing the mutated protein through a cell-free system [21].

- Benefit: This DBTL (Design-Build-Test-Learn) framework enables iterative exploration of protein sequence space to build specialized biocatalysts in parallel, dramatically accelerating data generation [21].

Problem: Handling a Highly Branched Metabolic Pathway My pathway is branched, leading to off-target side products and a complex production landscape that is difficult for the model to learn.

Answer: A well-chosen regression model can successfully navigate complex, branched pathways.

- Solution: Use a sparse sampling strategy to build a regression model. For instance, one study optimized a highly branched five-enzyme violacein biosynthetic pathway by training a regression model on a random sample comprising just 3% of the total combinatorial library [1]. The model was then able to predict genotypes that preferentially produced each of the pathway's distinct products.

- Model Choice: The study employed a supervised ridge regression model, which is well-suited for handling correlated predictors and preventing overfitting, especially with sparse data [21] [1]. This demonstrates that even with complex pathway architectures, sparse data can be sufficient for effective optimization.

Problem: Low Predictive Power for Substrate Specificity The model struggles to predict which substrates will bind effectively to engineered enzymes.

Answer: Incorporate algorithms that explicitly model the interactions between enzymes and substrates.

- Advanced Solution: Leverage a cross-attention algorithm within your model architecture. This algorithm operates on two input sequences—a source and a target. In the context of enzyme engineering, given an enzyme-substrate complex (the source sequence), the model can be trained to predict the specific interactions between amino acid residues of the enzyme and chemical groups of the substrate [28].

- Outcome: This approach allows the model to understand the physical and chemical basis of binding, moving beyond simple correlation to a more causal understanding. One implementation of this, the EZSpecificity model, achieved a 91.7% accuracy in identifying the correct reactive substrate when validated by experiments [28].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ: What types of regression models are most effective for sparse data in enzyme engineering?

Ridge regression is a highly effective and user-friendly choice. It has been successfully applied to predict enzyme variants with improved activity for pharmaceutical synthesis, demonstrating 1.6- to 42-fold improved activity relative to the parent enzyme [21]. Its key advantage is that it helps prevent overfitting—a common risk with sparse data—by penalizing the size of the regression coefficients. Furthermore, its performance can be enhanced by augmenting it with an evolutionary zero-shot fitness predictor, which provides a prior based on related enzyme homologs [21].

FAQ: How sparse can my data be before the model becomes unreliable?

There is no universal threshold, but success has been achieved with remarkably small sample sizes relative to the total combinatorial space. In one landmark study, a regression model trained on a random sample of just 3% of a combinatorial library was sufficient to predict high-performing strains for a five-enzyme pathway [1]. The reliability depends more on the quality and representativeness of the sampled data points across the expression space than on the absolute quantity. The goal is to sample the multi-dimensional grid of expression space sparsely but smartly to fit a predictive function [1].

FAQ: Can this approach be used for multi-objective optimization, such as balancing activity and stability?

While the primary focus in the cited literature is on optimizing a single objective like enzyme activity for a specific reaction, the regression framework is extensible to multi-objective optimization. The core idea involves mapping the sequence-function relationship for the desired phenotypes [21]. You would need to generate a dataset where you measure all relevant objectives (e.g., activity, thermostability, expression yield) for your library of enzyme variants. A multivariate regression model could then be trained to predict all these outcomes simultaneously, allowing you to identify variants that represent the best compromise between your competing objectives.

FAQ: We are developing a new enzyme and lack a large historical dataset. Is this method still applicable?

Absolutely. This methodology is specifically designed for scenarios where you start with little to no data. The process begins with using the integrated high-throughput platforms to rapidly generate your initial, sparse dataset from a combinatorially designed library [21] [1]. This first-round data is then used to train the initial regression model, which predicts the next set of promising variants to test. This creates an iterative DBTL cycle: the new experimental results are fed back into the model, which is retrained and becomes increasingly accurate with each round, allowing you to navigate the fitness landscape efficiently from scratch [21].

Experimental Protocol: ML-Guided Enzyme Engineering

The following protocol is adapted from studies that successfully used regression modeling to engineer amide bond-forming enzymes [21].

1. Design: Define Objective and Construct Library

- Objective Identification: Select a desired chemical transformation (e.g., synthesis of a specific pharmaceutical).

- Library Design: Choose a parent enzyme with known promiscuity. Identify target residues for mutation (e.g., all residues within 10 Ã… of the active site and substrate tunnels). Design a library to perform site-saturation mutagenesis on these residues.

2. Build: Rapid Library Construction via Cell-Free System

- Cell-Free DNA Assembly: Use a PCR-based method with mismatched primers to introduce mutations. Digest the parent plasmid with DpnI and perform Gibson assembly to form mutated plasmids.

- Prepare Linear Expression Templates (LETs): Amplify the mutated genes via a second PCR to create LETs, which will serve as direct templates for protein synthesis. This avoids cell-based cloning [21].

3. Test: High-Throughput Functional Assay

- Cell-Free Protein Expression: Synthesize enzyme variants directly from the LETs using a cell-free gene expression (CFE) system.

- Activity Screening: Under industrially relevant conditions (e.g., low enzyme loading, high substrate concentration), test each variant for its ability to catalyze the target reaction. Use analytical methods like HPLC or LC-MS to quantify conversion rates or product formation.

4. Learn: Train Regression Model and Predict

- Data Collection: Compile the sequence of each variant (genotype) with its corresponding activity measurement (phenotype).

- Model Training: Train an augmented ridge regression model on this dataset. The model uses the sequence information and, if available, evolutionary data to learn the sequence-function relationship.

- Prediction: Use the trained model to predict the activity of all possible variants in the theoretical sequence space that was not experimentally tested. The model outputs a ranked list of predicted high-performing variants for the next experimental cycle.

The workflow for this iterative DBTL cycle is summarized in the following diagram:

Table 1: Performance of Ridge Regression Model in Enzyme Engineering

| Target Product (Pharmaceutical) | Fold Improvement in Enzyme Activity (vs. Wild-Type) | Key Model Features | Experimental Validation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moclobemide [21] | Not Specified | Augmented Ridge Regression | Cell-free functional assay & LC-MS/HPLC |

| Metoclopramide [21] | Not Specified | Augmented Ridge Regression | Cell-free functional assay & LC-MS/HPLC |

| Cinchocaine [21] | Not Specified | Augmented Ridge Regression | Cell-free functional assay & LC-MS/HPLC |

| Various small molecule pharmaceuticals [21] | 1.6 to 42 | Augmented Ridge Regression | Cell-free functional assay & LC-MS/HPLC |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Protocol | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free Gene Expression (CFE) System [21] | Rapid, in vitro synthesis and testing of enzyme variants without cell-based cloning. | Enables high-throughput production of sequence-defined protein libraries. |

| Linear DNA Expression Templates (LETs) [21] | Serve as direct templates for protein synthesis in the CFE system, streamlining the workflow. | Generated by PCR amplification of mutated genes. |

| Ridge Regression Model [21] | Predicts enzyme variant fitness from sequence data, guiding the next design cycle. | Can be augmented with evolutionary zero-shot predictors for improved accuracy. |

| Cross-Attention Algorithm [28] | Models specific interactions between enzyme amino acids and substrate chemical groups. | Used in EZSpecificity model to predict binding with high accuracy (91.7%). |

| Promoter Set for Expression Tuning [1] | A characterized set of DNA promoters used to combinatorially adjust enzyme expression levels. | Used in yeast to balance flux in a multi-enzyme pathway. |

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Enzyme-Substrate Binding Prediction with Cross-Attention

This diagram illustrates the mechanism of a cross-attention algorithm used to predict enzyme-substrate interactions, a key for understanding specificity.

Sparse Sampling for Regression Modeling

This workflow shows how a small, random sample from a large combinatorial library is used to train a predictive model.

Active Learning and Evolutionary Algorithms for Guided Search

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental difference between traditional Directed Evolution (DE) and methods enhanced with Active Learning?

Traditional DE is an empirical, greedy hill-climbing process on a high-dimensional fitness landscape. It involves iterations of random mutagenesis and screening but can become trapped at local optima, especially on rugged fitness landscapes dominated by epistatic (non-additive) effects [29] [30]. In contrast, Active Learning-assisted Directed Evolution (ALDE) and similar workflows like METIS use machine learning models to guide experiment selection [29] [31]. They iteratively learn from collected data to propose the most informative subsequent experiments, enabling a more efficient exploration of the sequence space and a better navigation of epistatic interactions [30].

2. My optimization has stalled. What could be the cause?

A common cause is epistasis, where the effect of a mutation depends on the presence of other mutations, creating a rugged fitness landscape that is difficult to traverse with greedy methods [29] [30]. This is frequently observed when targeting enzyme active sites or binding surfaces [30]. To overcome this, consider switching from a simple DE approach to an Active Learning strategy. Machine learning models are better equipped to capture these non-additive effects and propose combinatorial mutations that work well together [29] [30].

3. How do I choose a machine learning model for my optimization campaign?

The choice depends on your dataset size and the complexity of your problem. For limited datasets typical in biological optimization (e.g., tens to hundreds of data points per round), tree-based models like XGBoost have been shown to outperform deep neural networks, which generally require larger datasets [31]. Furthermore, for protein engineering, using frequentist uncertainty quantification has been found to work more consistently than some Bayesian approaches in an active learning context [29].

4. What is the role of "zero-shot" predictors?

Zero-shot (ZS) predictors estimate protein fitness without prior experimental data on your specific objective. They leverage auxiliary information like evolutionary data, predicted stability, or structural information [30]. They can be used to enrich your initial training library with variants that are more likely to be functional, a strategy known as focused training (ftMLDE), which can significantly improve the success rate of machine learning-assisted directed evolution [30].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Performance in Optimizing Multi-Enzyme Pathways

- Problem: Optimizing the expression levels of multiple enzymes in a pathway sequentially is time-consuming and often fails to find the global optimum due to complex, non-linear interactions.

- Solution: Implement a combinatorial optimization strategy. Instead of optimizing one variable at a time, use methods that generate diversity in the levels of all pathway components simultaneously.

Protocol: The following steps outline a generalized combinatorial optimization workflow using active learning [31] [22]:

- Define the System: Identify all factors to optimize (e.g., concentrations of enzymes, salts, cofactors). Define a quantifiable objective function (e.g., product yield, fluorescence).

- Initial Library: Start with an initial dataset. This can be a small, randomly sampled set of conditions or a set enriched by a zero-shot predictor [30].

- Active Learning Loop:

- Train Model: Train a machine learning model (e.g., XGBoost) on all collected data.

- Propose Experiments: Use the model's predictions and uncertainty quantification to select the next batch of promising conditions to test. This balances exploration and exploitation.

- Wet-Lab Experiment: Conduct the proposed experiments and measure the objective function.

- Update Data: Add the new data to the training set.

- Iterate: Repeat the loop until the objective is met or the budget is exhausted.

Issue 2: Navigating Rugged, Epistatic Fitness Landscapes in Protein Engineering

- Problem: Recombining beneficial single mutations results in low-fitness variants, indicating strong negative epistasis.

- Solution: Use Active Learning-assisted Directed Evolution (ALDE) to efficiently search combinatorial sequence space [29].

Protocol: Application of ALDE for a challenging 5-residue active site optimization [29]:

- Define Design Space: Select

kepistatic residues for simultaneous mutagenesis (e.g., 5 residues = 20^5 possible variants). - Initial Data Collection: Synthesize and screen an initial library of variants mutated at all

kpositions. - Computational Ranking:

- Train a supervised ML model on the collected sequence-fitness data.

- Use an acquisition function (e.g., upper confidence bound) on the trained model to rank all sequences in the design space.

- Iterative Rounds: Select the top N ranked variants for the next round of wet-lab experimentation. Use the new data to update the model and repeat for several rounds.

- Define Design Space: Select

Issue 3: High Experimental Cost for Optimizing Complex Metabolic Networks

- Problem: The number of possible experimental conditions for a network with many variables is astronomically high, making exhaustive testing impossible.

- Solution: Employ a versatile active learning workflow like METIS for data-driven optimization with minimal experiments [31].

Protocol: METIS workflow for a 27-variable CO2-fixation cycle [31]:

- Setup: Define all variable factors and their ranges within the METIS Google Colab interface.

- Initialization: Start with a small, random set of experiments (e.g., 20 conditions).

- Automated Workflow:

- Input your experimental results into METIS.

- The built-in XGBoost model suggests the next set of conditions to test.

- Analysis: The workflow provides optimized conditions and analyzes feature importance, identifying the system's bottlenecks and key components.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology: ALDE for Enzyme Engineering

The following table summarizes the key steps from the successful application of ALDE to optimize a protoglobin (ParPgb) for a non-native cyclopropanation reaction [29].

- Objective: Optimize the difference between the yield of

cis-2aandtrans-2acyclopropanation products. - Design Space: Five epistatic residues (W56, Y57, L59, Q60, F89) in the enzyme's active site.

| Step | Description | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|