BioBrick vs BglBrick vs Golden Gate: A Comprehensive Comparative Analysis for Synthetic Biology and Drug Development

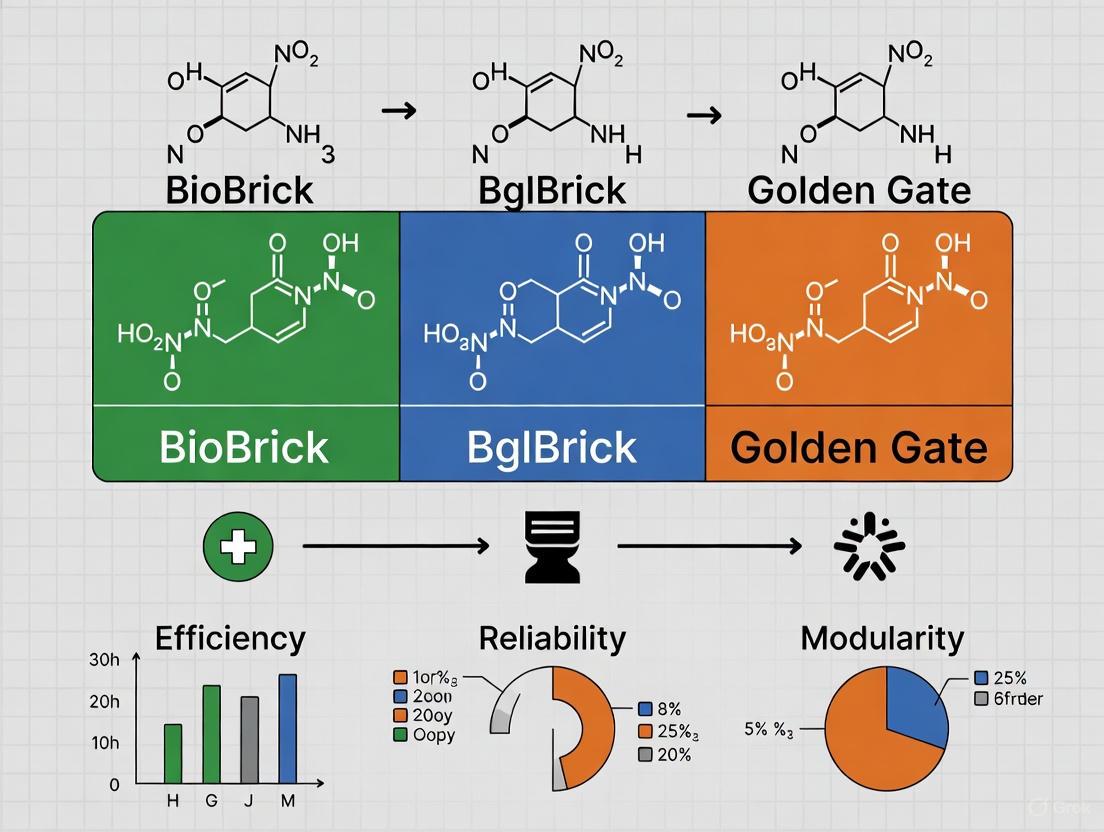

This article provides a detailed comparative analysis of three foundational DNA assembly standards in synthetic biology: BioBrick, BglBrick, and Golden Gate.

BioBrick vs BglBrick vs Golden Gate: A Comprehensive Comparative Analysis for Synthetic Biology and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a detailed comparative analysis of three foundational DNA assembly standards in synthetic biology: BioBrick, BglBrick, and Golden Gate. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles, methodological applications, and practical troubleshooting for each standard. By synthesizing current research and technical specifications, this analysis offers a strategic framework for selecting the optimal assembly method based on project requirements, focusing on factors such as assembly speed, scar formation, modularity, and suitability for complex genetic constructs like protein fusions and multigene pathways. The review concludes with future directions and implications for biomedical research, highlighting emerging hybrid approaches and the critical role of standardization in advancing therapeutic development.

The Building Blocks of Synthetic Biology: Understanding BioBrick, BglBrick, and Golden Gate Foundations

Core Principles of the BioBrick Assembly Standard and Idempotent Assembly

The engineering of biological systems relies on the ability to reliably and predictably combine genetic parts. Standardized assembly methods provide the foundational tools for this process, enabling the construction of complex genetic circuits and pathways in a reproducible manner. Among the earliest and most influential standards is the BioBrick assembly standard, which introduced the powerful concept of idempotent assembly—a process where any two standard parts can be combined to create a new composite part that is itself a standard part [1]. This principle allows for the distributed production of compatible biological parts and simplifies the automation of DNA fabrication [2] [1]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the core BioBrick standard (often associated with RFC 10), the BglBrick standard (RFC 21), and the more modern Golden Gate assembly method. We will objectively compare their performance, supported by experimental data, to inform researchers and scientists in selecting the most appropriate tool for their projects.

Core Principles of BioBrick and Idempotent Assembly

The Idempotent Assembly Concept

Idempotence, in the context of genetic assembly, means that the operation of combining two standard parts always produces a result that conforms to the same standard as the original components. This is a critical feature for hierarchical and iterative construction of larger DNA devices. A researcher anywhere in the world can design a part conforming to the standard, and it will be physically composable with any other standard part, without prior coordination between the engineers [1]. This approach transforms genetic engineering from a technically intensive art into a more predictable, design-based discipline [2].

Technical Specifications of BioBrick RFC 10

The original BioBrick standard (RFC 10) employs a specific set of restriction enzymes to enable idempotent assembly. The key enzymes and their recognition sites are integrated into a prefix and suffix that flank every biological part.

Table 1: Key Restriction Enzymes in BioBrick RFC 10

| Restriction Enzyme | Recognition Site | Location | Role in Assembly |

|---|---|---|---|

| EcoRI | GAATTC | Prefix | Provides an upstream boundary for the part. |

| XbaI | TCTAGA | Prefix | Creates a compatible end with SpeI for ligation. |

| SpeI | ACTAGT | Suffix | Creates a compatible end with XbaI for ligation. |

| PstI | CTGCAG | Suffix | Provides a downstream boundary for the part. |

The assembly process involves digesting two parts to be joined with XbaI and SpeI. These enzymes generate compatible cohesive ends that allow the parts to be ligated together head-to-tail. The crucial feature of this design is that the ligation produces an 8-base pair (bp) "scar" sequence (TACTAGAG) that no longer contains either the original XbaI or SpeI sites [2]. This scar sequence is immutable and prevents the composite part from being cut again by these enzymes in subsequent assembly steps, thus ensuring idempotence.

The following diagram illustrates the core principle of idempotent assembly in the BioBrick standard:

Comparative Analysis of Assembly Standards

While the original BioBrick standard was groundbreaking, its limitations for certain applications spurred the development of new standards. The table below provides a high-level comparison of three major standards.

Table 2: Overview of Major DNA Assembly Standards

| Feature | BioBrick (RFC 10) | BglBrick (RFC 21) | Golden Gate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Defining Feature | Original idempotent standard | Optimized for protein fusions | Uses Type IIS restriction enzymes |

| Key Enzymes | EcoRI, XbaI, SpeI, PstI | EcoRI, BglII, BamHI, XhoI | Type IIS (e.g., BsaI) |

| Scar Size | 8 bp | 6 bp | User-defined, can be scarless |

| Scar Sequence | TACTAGAG | GGATCT | Varies |

| Protein Fusion | Not suitable (scar contains stop codon) | Excellent (scar encodes Gly-Ser) | Excellent (can be designed to be scarless) |

| Key Advantage | Established, large part repository | Robust enzymes, innocuous peptide scar | Ultimate flexibility, high efficiency, multi-part assembly |

| Main Disadvantage | Unsuitable for translational fusions | Still leaves a small scar | Requires more initial design and tool development |

The BglBrick Standard (RFC 21)

The BglBrick standard was developed to directly address the primary shortcoming of RFC 10: its inability to create in-frame protein fusions [2]. The 8-bp scar in RFC 10 assemblies not only causes a frameshift but also encodes a stop codon (TAG), making it impossible to create functional fusion proteins [2] [3].

Technical Specifications: BglBrick parts are flanked by BglII (AGATCT) on the 5' end and BamHI (GGATCC) on the 3' end, within a larger prefix and suffix that also include EcoRI and XhoI sites [2] [3]. When a part is digested with BglII and BamHI, the compatible ends ligate to form a 6-bp scar (GGATCT). This scar sequence codes for the dipeptide glycine-serine (Gly-Ser), which is a flexible and innocuous linker widely used in protein engineering in various hosts, including E. coli, yeast, and humans [2]. Furthermore, BglII and BamHI are robust enzymes with high cutting efficiency and are unaffected by Dam methylation, which can plague other standards like the Biofusion standard (RFC 23) [2].

Experimental Validation: The utility of the BglBrick standard has been demonstrated in diverse applications. Researchers have used it to construct libraries of gene expression devices with a wide range of expression profiles and to create chimeric, multi-domain fusion proteins [2]. Its robustness has also been leveraged to build large sets of compatible plasmids, combining different replication origins, inducible promoters, and antibiotic markers for metabolic engineering applications [4]. The quantitative characterization of these vectors, documented in standardized datasheets, provides valuable data for predicting gene expression when multiple plasmids are used in a single host [4].

The Golden Gate Assembly Standard

Golden Gate assembly represents a more flexible and powerful modern approach. It utilizes Type IIS restriction enzymes, which cut DNA outside of their recognition site, allowing for the creation of any user-specified cohesive end sequence [5] [6]. This method is highly efficient for one-pot, multi-part assembly and is the basis for several standardized toolkits like MoClo and Golden Braid [5].

Technical Specifications and Advantage: The key advantage of Golden Gate is that the scar sequence between parts is not fixed. By designing the overhangs appropriately, it is possible to create scarless junctions, a significant benefit for applications sensitive to extra nucleotides, such as the precise assembly of coding sequences [6]. A single Type IIS enzyme (e.g., BsaI) can be used to excise multiple parts from donor vectors and assemble them in a defined order in a single reaction, as the non-palindromic overhangs ensure correct and directional assembly [5] [6]. The ability to perform hierarchical assembly makes Golden Gate exceptionally suited for constructing very large and complex genetic systems.

Experimental Evidence: Golden Gate's efficiency and flexibility have made it a preferred choice for ambitious projects. It has been extensively used for assembling entire metabolic pathways in libraries of constructs, allowing researchers to sample a vast "design space" of enzyme expression levels to optimize production [6]. Its reliability has been proven in diverse organisms, including plants, yeast, and bacteria [5] [6].

Quantitative Comparison of Assembly Scars

The nature of the scar sequence is a critical differentiator between these standards, directly impacting their suitability for various applications. The table below summarizes the key scar characteristics.

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Assembly Scar Sequences

| Assembly Standard | Scar Sequence | Scar Length | Encoded Amino Acids | Functional Impact on Protein Fusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BioBrick (RFC 10) | TACTAGAG | 8 bp | Tyr-Arg (and stop codon) | Non-functional (causes frameshift and premature termination) |

| BglBrick (RFC 21) | GGATCT | 6 bp | Gly-Ser | Functional (innocuous, flexible linker) |

| Silver (RFC 23) | ACTAGA | 6 bp | Thr-Arg (AGA is a rare E. coli codon) | Functional, but potential inefficiency |

| BB-2 (RFC 12) | GCTAGT | 6 bp | Ala-Ser | Functional (benign, N-end rule safe) |

| Golden Gate | User-defined | User-defined | User-defined | Can be designed to be scarless and functionally neutral |

Experimental data confirms the functional implications of these scars. A study directly comparing the impact of various assembly scars at the junction between a coding sequence and its upstream region found that scars can significantly affect mRNA structure, ribosome binding site accessibility, and ultimately, gene expression levels [6]. This evidence underscores the advantage of scar-minimizing standards like Golden Gate and BglBricks for fine-tuned genetic engineering.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Idempotent Assembly Workflow

The following diagram and protocol outline the general workflow for a typical BioBrick-style idempotent assembly, which is conceptually similar for RFC 10 and RFC 21.

Detailed Protocol for BglBrick Assembly [2] [4]:

Digestion: In separate tubes, set up restriction digestion reactions for the insert part and the destination vector. A typical reaction mixture includes:

- DNA (part or vector): ~100-200 ng

- Restriction Enzyme 1 (BglII for insert, BamHI for vector): 1 µL

- Restriction Enzyme 2 (BamHI for insert, BglII for vector): 1 µL

- 10x Restriction Enzyme Buffer: 2 µL

- Nuclease-free water to 20 µL

- Incubate at 37°C for 1-2 hours.

Ligation: Combine the digested and purified fragments.

- Prepared vector backbone: 50 ng

- Prepared insert part: 3:1 molar ratio over vector

- 10x T4 DNA Ligase Buffer: 1 µL

- T4 DNA Ligase: 1 µL

- Nuclease-free water to 10 µL

- Incubate at room temperature for 1 hour or 16°C for 4-6 hours.

Transformation: Transform the entire ligation reaction into chemically competent E. coli cells via heat shock, plate onto LB agar containing the appropriate selective antibiotic, and incubate overnight at 37°C.

Verification: Screen resulting colonies by colony PCR or analytical restriction digest. The final construct must be verified by DNA sequencing to ensure the assembly is correct and that no mutations have been introduced.

Protocol for Characterizing Expression Vectors

To generate quantitative data on the performance of vectors built with these standards (e.g., for a comparative datasheet), the following experimental approach can be used, as demonstrated for BglBrick vectors [4]:

- Strain and Growth: Transform the constructed plasmid into relevant host strains (e.g., E. coli DH1 or BLR(DE3)). Grow cultures in selected media (e.g., LB, TB, M9).

- Inducer Dose-Response: Induce cultures with a range of inducer concentrations (e.g., 0-500 µM IPTG, 0-200 nM anhydrotetracycline).

- Measurement: Monitor cell density (OD₆₀₀) and reporter protein output (e.g., fluorescence for RFP or GFP) over time (e.g., 18 hours).

- Data Analysis: Calculate specific fluorescence (fluorescence/OD₆₀₀) to normalize for cell density. Plot these values over time and as a function of inducer concentration to generate comprehensive expression profiles.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for DNA Assembly and Characterization

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| BglII Restriction Enzyme | Cuts within the BglBrick prefix (AGATCT) | Excising an insert part for BglBrick (RFC 21) assembly [2] |

| BamHI Restriction Enzyme | Cuts within the BglBrick suffix (GGATCC) | Preparing the vector backbone for BglBrick assembly [2] |

| T4 DNA Ligase | Joins compatible cohesive DNA ends | Ligating digested inserts and vectors in restriction-ligation assembly [2] |

| E. coli DB3.1 | ccdB-tolerant strain | Propagating vectors with the ccdB negative selection marker [1] |

| pSB1C3 | Standard high-copy BioBrick plasmid backbone | Propagating and distributing basic parts from the Registry [7] |

| Reporter Proteins (RFP/GFP) | Encoded genes for visual phenotyping | Quantifying promoter strength and gene expression in characterized vectors [4] |

| Inducer Molecules (IPTG, aTc) | Chemicals that trigger inducible promoters | Titrating gene expression levels in dose-response experiments [4] |

In synthetic biology, the ability to reliably assemble genetic parts is fundamental to engineering biological systems. The original BioBrick assembly standard pioneered the concept of standardized biological parts, enabling the construction of genetic circuits through a simple, iterative process [8]. However, a significant limitation hampered its application in protein engineering: the assembly process left behind an 8-nucleotide scar sequence ("TACTAGAG") that encoded a tyrosine followed by a stop codon, making it unsuitable for creating functional fusion proteins [8]. This critical shortcoming spurred the development of new standards, leading to the creation of BglBricks, a flexible alternative designed to overcome this barrier. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the BglBrick standard against its predecessor, the classic BioBrick, and the contemporary Golden Gate method, presenting objective performance data and detailed protocols to inform researchers and drug development professionals in their selection of cloning strategies.

Comparative Analysis of DNA Assembly Standards

The evolution of DNA assembly standards reflects a continuous effort to balance simplicity, efficiency, and functional output. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of the three primary standards discussed in this guide.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of BioBrick, BglBrick, and Golden Gate Assembly Standards

| Feature | BioBrick (Original) | BglBrick | Golden Gate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Restriction Enzymes | XbaI & SpeI | BglII & BamHI | Type IIS (e.g., BsaI, BsmBI) |

| Assembly Scar | 8 bp scar (TACTAGAG) | 6 bp scar (GGATCT) | Typically scarless |

| Scar Translation | Encodes Tyr-Stop codon | Encodes Gly-Ser linker | User-defined |

| Primary Application | Genetic circuit assembly | Protein fusions & genetic devices | Multi-part, seamless assembly |

| Assembly Throughput | Sequential (2 parts per cycle) | Sequential (2 parts per cycle) | Parallel (Multiple parts per cycle) |

| Key Advantage | Simplicity, standardization | Enables in-frame protein fusions | High efficiency & multi-part capability |

| Main Limitation | Unsuitable for protein fusions | Sequential assembly can be slow | Requires elaborate vector libraries |

The BglBrick standard specifically addresses the protein fusion problem by employing BglII and BamHI restriction enzymes. These robust cutters generate compatible cohesive ends that, when ligated, form a 6-nucleotide scar sequence ("GGATCT") [8]. This sequence encodes a glycine-serine peptide linker, which is a flexible and innocuous spacer widely used in recombinant protein construction in various host systems, including E. coli, yeast, and human cells [8]. This strategic modification preserved the iterative, idempotent nature of the original BioBrick standard while unlocking its potential for protein engineering.

Meanwhile, other strategies have emerged. Golden Gate assembly uses Type IIS restriction enzymes, which cut outside their recognition site, allowing for predefined overhangs and typically scarless fusion of DNA parts [9]. While extremely powerful for assembling multiple fragments simultaneously, its reusability for endless assembly can require complex hierarchical vector systems like MoClo [9] [10]. More recent innovations like GoldBricks and PS-Brick have sought to combine the advantages of different systems, integrating Type IIS enzymes into a BioBrick-like format for faster, more efficient assembly with reduced scarring [9] [10].

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

To objectively evaluate the practical performance of these standards, we can examine data from implementation studies. A systematic comparative analysis of cloning techniques in E. coli demonstrated that Golden Gate assembly, which leverages similar principles as BglBricks but for multi-fragment assembly, significantly enhanced cloning efficiency and precision over classical methods [11]. The BglBrick system itself has proven highly reliable. In a foundational study, the assembly reaction exhibited high efficiency, and the resulting constructs were successfully used in three distinct applications: creating constitutive gene expression devices with a wide dynamic range, constructing chimeric multi-domain proteins, and targeted genomic integration in E. coli [8].

Table 2: Experimental Outcomes from BglBrick and Related Studies

| Standard | Reported Efficiency/Accuracy | Key Experimental Demonstration | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| BglBrick | High efficiency in assembly and transformation | Construction of functional multi-domain fusion proteins and gene expression devices. | [8] |

| Golden Gate | >90% accuracy in multi-part assembly | Assembly of up to 24 parts in a single reaction with high accuracy. | [9] |

| PS-Brick | ~90% accuracy, 10⁴–10⁵ CFUs/µg DNA | Iterative DBTL cycles for metabolic engineering of threonine and 1-propanol production. | [10] |

| Modified BglBrick (L. lactis) | Successful simultaneous expression | Assembly and controlled co-expression of three model proteins in Lactococcus lactis. | [12] |

The versatility of the BglBrick standard is further highlighted by its adaptation for other organisms. Researchers successfully introduced a modified BglBrick system into the lactic acid bacterium Lactococcus lactis, enabling straightforward assembly of multiple gene cassettes and the controlled simultaneous expression of three proteins [12]. This demonstrates the standard's flexibility and portability beyond its original host, E. coli.

Essential Protocols for BglBrick Assembly

Basic BglBrick Assembly Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core enzymatic process of the BglBrick assembly, highlighting how the scar sequence is formed.

The fundamental BglBrick assembly protocol is as follows:

- Vector and Insert Digestion: A BglBrick part (insert) and a BglBrick-compatible destination vector are digested with BglII and BamHI restriction enzymes. These enzymes generate compatible cohesive ends that cannot self-ligate.

- Ligation: The digested and purified vector and insert are mixed and ligated using T4 DNA ligase. The compatible ends from BglII and BamHI anneal and are ligated together.

- Formation of Scar: The ligation results in a fusion product that contains a 6-bp scar sequence (GGATCT) between the two original parts. This scar no longer contains recognition sites for BglII or BamHI, making the composite part a new BglBrick part that can be used in further rounds of assembly.

- Transformation and Verification: The ligation product is transformed into an appropriate host strain (e.g., E. coli DH5α), and successful clones are verified by colony PCR, diagnostic restriction digests, and sequencing.

Advanced Implementation: Multi-Gene Assembly

For assembling more complex constructs with multiple genes, the process becomes iterative. The diagram below outlines a multi-gene assembly strategy using BglBricks, as demonstrated in L. lactis [12].

This advanced protocol for multi-cassette assembly, as optimized for L. lactis, involves:

- Specialized Vector: Using a custom plasmid (e.g., pNBBX) containing specific sites like NheI, BglII, BclI, and XhoI [12].

- Upstream Cloning: The first expression cassette (containing PnisA, Gene of Interest 1, and a terminator) is cloned into the backbone using NheI and BglII/BclI digestion and ligation.

- Downstream Cloning: A second cassette is inserted using BclI and XhoI sites, leveraging the compatibility between the BglII and BclI overhangs to add the new part downstream, with each junction containing the Gly-Ser encoding scar [12].

- Expression Check: The final multi-gene plasmid is transformed into the host, and protein expression is induced and validated, for example, via nisin induction in L. lactis [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of the BglBrick standard requires a set of core reagents. The following table lists essential materials and their functions based on the protocols from the cited research.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for BglBrick Assembly

| Reagent / Material | Function / Specification | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Restriction Enzymes: BglII & BamHI | Core enzymes for generating compatible ends for assembly. | Digesting parts and vectors for basic BglBrick assembly [8]. |

| T4 DNA Ligase | Joins the compatible cohesive ends of digested vector and insert. | Ligation reaction following digestion [8]. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Amplifies DNA parts and vectors with minimal errors. | Generating parts via PCR for cloning into holding vectors [9]. |

| BglBrick-Compatible Vectors | Plasmid backbones with appropriate prefix and suffix sequences. | pNBBX for L. lactis [12]; various E. coli BglBrick vectors [8]. |

| Chemically Competent E. coli | For transformation and propagation of assembled plasmids. | E. coli DH5α for cloning [9] [8]. |

| Selection Antibiotics | Selective pressure for maintaining plasmids. | Ampicillin, kanamycin, or chloramphenicol at standard concentrations [9] [12]. |

The BglBrick standard represents a critical evolutionary step in DNA assembly technology, directly addressing the primary limitation of the original BioBrick system by enabling the construction of in-frame protein fusions through a benign glycine-serine scar. While newer methods like Golden Gate offer superior speed for multi-part assembly, BglBricks maintain a strong position due to their conceptual simplicity, reliability, and proven utility in constructing functional genetic devices and multi-domain proteins. For research and drug development projects focused on protein engineering, metabolic pathway construction, and requiring a straightforward, iterative cloning workflow, the BglBrick standard remains a powerful and accessible tool in the synthetic biology arsenal.

{#topic}

Golden Gate Assembly: Revolutionizing Cloning with Type IIS Restriction Enzymes

A Comparative Analysis of DNA Assembly Standards

In the field of synthetic biology, the ability to efficiently and accurately assemble DNA constructs is foundational. Techniques like Golden Gate Assembly, BioBrick, and BglBrick have created distinct standards for part assembly, each with unique strengths. Golden Gate Assembly has emerged as a particularly powerful method, using Type IIS restriction enzymes to enable the seamless, one-pot assembly of multiple DNA fragments. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these cloning standards, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, to inform researchers and drug development professionals in their selection of appropriate methodologies.

Cloning Standards at a Glance

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of the three major assembly standards, highlighting key differences in their mechanisms and outcomes.

| Feature | Golden Gate Assembly | BioBrick Standard | BglBrick Standard |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Enzymes | Type IIS (e.g., BsaI, BsmBI) [13] [14] | Type IIP (XbaI and SpeI) [8] | Type IIP (BglII and BamHI) [8] |

| Assembly Scar | Scarless (seamless) [13] [15] | 8-bp scar (TACTAGAG) [8] | 6-bp scar (GGATCT) [8] |

| Scar Translation | N/A (Scarless) | Encodes tyrosine and a stop codon [8] | Encodes glycine-serine [8] |

| Suitability for Protein Fusions | Excellent (seamless) | Poor (due to stop codon and frame shift) [8] | Good (innocuous peptide linker) [8] |

| Multi-Fragment Assembly | Excellent (Up to 35+ in one pot) [16] | Iterative (one fragment at a time) | Iterative (one fragment at a time) |

| Typical Assembly Process | One-pot digestion & ligation [13] | Multi-step digestion & ligation | Multi-step digestion & ligation |

Performance and Experimental Data

Golden Gate Assembly's performance is demonstrated through its ability to assemble a high number of fragments with remarkable fidelity. The following table summarizes key experimental findings.

| Experiment / System | Number of Fragments Assembled | Reported Efficiency / Fidelity | Key Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data-Optimized Assembly Design [16] | 35 | Successful one-pot assembly | T4 DNA Ligase, BsaI-HFv2, optimized overhangs |

| lacI/lacZ Cassette Assembly [17] | 24 | 90.7% fidelity (correct assemblies) | BsaI-HFv2, T4 DNA Ligase, 30 cycles of 37°C/16°C |

| lacI/lacZ Cassette Assembly [17] | 12 | 99.5% fidelity (correct assemblies) | BsaI-HFv2, T4 DNA Ligase, 30 cycles of 37°C/16°C |

| MoClo System [15] | Up to 6 per step (hierarchical) | Varies with complexity | Uses BpiI (Golden Gate) for tiered assembly |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: A Multi-Fragment Golden Gate Assembly

The high efficiency of Golden Gate Assembly is achieved through precise experimental design. Below is a generalized protocol for a multi-fragment assembly, based on methodologies that have successfully assembled up to 35 fragments [13] [16] [17].

- Reaction Setup: A typical 20 µl reaction mixture includes:

- 75 ng of the destination vector [13]

- Insert fragments at a 2:1 molar ratio (insert:vector) [13]

- 2 µl of 10X T4 DNA Ligase Buffer (providing ATP) [13]

- 1-2 µl (10-20 units) of a Type IIS restriction enzyme (e.g., BsaI-HFv2) [13]

- 0.25-0.5 µl (500-1000 units) of T4 DNA Ligase [13]

- Nuclease-free water to volume

- Thermal Cycling: The reaction is incubated in a thermal cycler. The protocol varies based on the number of fragments [13]:

- For 2-4 fragments: 37°C for 1 hour, followed by 60°C for 5 minutes.

- For 5-10 fragments: 30 cycles of (37°C for 1 minute + 16°C for 1 minute), followed by 60°C for 5 minutes.

- For 11-20+ fragments: 30 cycles of (37°C for 5 minutes + 16°C for 5 minutes), followed by 60°C for 5 minutes.

- Transformation and Screening: Following the reaction, the assembly mixture is transformed into competent E. coli. The number of transformants will be inversely proportional to the complexity of the assembly. For high-complexity assemblies (e.g., 24 fragments), plating a larger volume (e.g., 100 µl of a 1 mL outgrowth) is recommended to obtain a sufficient number of colonies for screening [17]. Successful assemblies can be confirmed through colony PCR, restriction digest, and ultimately, sequencing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of Golden Gate Assembly relies on a core set of reagents and tools.

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Type IIS Restriction Enzymes | Cuts DNA outside recognition site to generate custom overhangs. | BsaI, BsmBI, BbsI, SapI; high-fidelity versions (e.g., BsaI-HFv2) are preferred [13] [17]. |

| DNA Ligase | Joins DNA fragments with complementary overhangs. | T4 DNA Ligase is most common and efficient [13] [16]. |

| Entry & Destination Vectors | Plasmid backbones for storing parts and assembling final constructs. | Designed with outward-facing Type IIS sites; may use negative selection markers (e.g., ccdB) to reduce background [18] [15]. |

| Software Tools | In silico design and validation of assembly. | Tools like SnapGene or Benchling visualize sites; data-optimized assembly design (DAD) tools predict high-fidelity overhangs [14] [16]. |

| High-Fidelity Overhangs | Pre-vetted junction sequences to maximize assembly accuracy. | Designed using ligase fidelity data to minimize mis-ligation; critical for >10 fragment assemblies [16] [17]. |

Visualizing Assembly Mechanisms and Comparisons

The following diagrams illustrate the core mechanism of Golden Gate Assembly and how it compares structurally to other standards.

Golden Gate Assembly Workflow

DNA Assembly Scar Comparison

Golden Gate Assembly represents a significant advancement in cloning technology, offering unmatched flexibility for the seamless and high-throughput construction of complex genetic systems. While legacy standards like BioBrick and BglBrick have played pivotal roles in the development of synthetic biology, the data-optimized, one-pot capability of Golden Gate makes it the superior choice for modern research and drug development projects requiring sophisticated DNA assembly.

Historical Context and Development of DNA Assembly Standards

The field of synthetic biology is built upon the foundational ability to design and construct novel DNA sequences. The standardization of DNA assembly methods has been critical to transforming genetic engineering from a technically intensive art into a purely design-based discipline [2]. Standardized assembly techniques allow genetic parts to be treated as interchangeable, reusable components, enabling the predictable construction of complex biological systems [19]. This comparative analysis examines the historical development and technical evolution of three significant DNA assembly standards: BioBrick, BglBrick, and Golden Gate. These standards represent key milestones in synthetic biology, each addressing specific limitations of its predecessors while introducing new capabilities for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. Understanding their relative advantages, experimental requirements, and performance characteristics is essential for selecting the appropriate methodology for specific research applications, from basic genetic circuits to complex metabolic pathway engineering.

Comparative Analysis of DNA Assembly Standards

The evolution from BioBrick to BglBrick and finally to Golden Gate assembly represents a trajectory toward greater flexibility, precision, and efficiency in DNA construction. The following table provides a comprehensive technical comparison of these three standards.

Table 1: Technical Comparison of DNA Assembly Standards

| Feature | BioBrick | BglBrick | Golden Gate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Enzymes | Type IIP (XbaI, SpeI) | Type IIP (BglII, BamHI) | Type IIS (e.g., BsaI, BsmBI) |

| Scar Sequence | 8 bp (TACTAGAG) [2] | 6 bp (GGATCT) [2] [10] | Scarless [20] [10] |

| Scar Translation | Encodes tyrosine-stop codon [2] | Encodes glycine-serine [2] [10] | N/A (Seamless) |

| Primary Advantage | Standardization & reusability | Protein fusion capability | Multi-fragment, scarless, one-pot assembly |

| Key Limitation | Unsuitable for protein fusions [2] | Scar still present | Requires more complex vector libraries [21] |

| Assembly Efficiency | Iterative but slow [10] | Iterative | Highly efficient & hierarchical [20] [21] |

| Ideal Application | Simple genetic circuits | Multi-domain protein expression | Complex pathway construction, library generation |

The BioBrick standard (BBF RFC 10) was the pioneering framework that introduced the concept of standardized biological parts. It uses iterative restriction enzyme digestion and ligation with Type IIP enzymes (XbaI and SpeI) to assemble basic parts into larger composite parts [2] [22]. A significant drawback of this system is the 8-nucleotide scar sequence it generates between joined parts. This scar encodes a tyrosine followed by a stop codon, making the standard unsuitable for constructing functional protein fusions—a critical limitation for metabolic engineering and protein engineering applications [2] [10].

The BglBrick standard (BBF RFC 21) was developed to directly address the protein fusion limitation of the original BioBrick system. It employs BglII and BamHI restriction enzymes, which create a 6-nucleotide scar sequence (GGATCT) that encodes a glycine-serine peptide linker [2]. This linker is generally innocuous in most protein fusion applications across various host systems, including E. coli, yeast, and humans [2]. While this represented a major advancement, the standard still leaves behind a scar sequence and relies on the same iterative assembly process as the original BioBricks.

The Golden Gate Assembly system represents a more radical departure from the BioBrick concept. Instead of Type IIP enzymes, it utilizes Type IIS restriction enzymes (such as BsaI and BsmBI), which cut outside of their recognition sites [20]. This key difference allows researchers to create custom, non-palindromic overhangs, enabling the seamless, scarless assembly of multiple DNA fragments in a single, one-pot reaction [20] [21]. Its versatility has led to the development of extensive standardized toolkits (e.g., MoClo, Golden Braid) for diverse organisms [21].

Table 2: Experimental and Practical Considerations

| Consideration | BioBrick | BglBrick | Golden Gate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction Scheme | Sequential, iterative cycles | Sequential, iterative cycles | One-pot, modular |

| Multi-part Assembly | Limited efficiency | Limited efficiency | High efficiency (10+ fragments) |

| Background | Moderate | Moderate | Very low [20] |

| Automation Potential | Moderate | Moderate | High |

| Toolkit Availability | Limited (iGEM Registry) | Specialized vector sets [19] | Extensive (MoClo, Golden Braid, etc.) [21] |

| Protocol Duration | Days for multi-part | Days for multi-part | < 3 hours hands-on time [20] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

BglBrick Assembly Workflow

The BglBrick standard is designed for idempotent assembly, meaning the resulting composite part can be used as a basic part in another round of assembly. The following protocol outlines the key experimental steps for assembling two BglBrick parts.

Detailed Protocol:

- Digestion: Incubate the recipient plasmid (containing the first part) and the donor plasmid (containing the second part) separately with the restriction enzymes BglII and BamHI. A typical reaction mixture might include 1 µg of plasmid DNA, 1X restriction enzyme buffer, 10 units of each enzyme, and nuclease-free water to a final volume of 20 µL. Incubate at 37°C for 1 hour [2].

- Ligation: Purify the digested DNA fragments and mix them in a ligation reaction. A standard reaction uses a 3:1 molar ratio of insert to vector, 1X T4 DNA ligase buffer, 400 units of T4 DNA ligase, and water to 20 µL. Incubate at 16°C for 4-16 hours [19].

- Transformation: Transform 2-5 µL of the ligation reaction into chemically competent E. coli cells via heat shock, plate onto LB agar with the appropriate antibiotic, and incubate overnight at 37°C [19].

- Screening & Verification: Select colonies, isolate plasmid DNA, and verify successful assembly by analytical digestion with EcoRI and XhoI (which flank the BglBrick part but do not cut internally) or by colony PCR. Sequence confirmation is recommended for final constructs [2] [19].

BglBrick Assembly Workflow

Golden Gate Assembly Workflow

Golden Gate assembly combines restriction digestion and ligation into a single-tube reaction, significantly streamlining the process. The following protocol is adapted for use with BsaI-HFv2, a commonly used Type IIS enzyme.

Detailed Protocol:

- Reaction Setup: In a single tube, combine 50-100 ng of the destination vector, equimolar amounts of each DNA part (typically 10-50 fmols each), 1X T4 DNA ligase buffer, 10 units of BsaI-HFv2, 400 units of T4 DNA ligase, and nuclease-free water to a final volume of 20 µL [20] [21].

- Thermocycling: Place the reaction in a thermocycler and run the following program:

- Transformation and Verification: Transform 1-2 µL of the reaction directly into competent E. coli cells. The design of the system ensures that only correctly assembled plasmids confer resistance, resulting in very low background. Verify constructs by colony PCR or analytical digestion [20].

Golden Gate One-Pot Assembly

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of these DNA assembly standards requires specific, high-quality reagents. The following table details the essential materials and their functions for the featured experiments.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DNA Assembly

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Type IIP Restriction Enzymes (BglII, BamHI, XbaI, SpeI) | Cut DNA at specific palindromic sequences to generate compatible ends for ligation. | High-fidelity (HF) versions reduce star activity. Must be compatible in a single buffer [2]. |

| Type IIS Restriction Enzymes (BsaI-HFv2, BsmBI-v2) | Cut outside recognition site to generate unique, user-defined 4-base overhangs. | Foundation of Golden Gate; efficiency is critical for one-pot success [20] [21]. |

| T4 DNA Ligase | Joins DNA fragments by catalyzing phosphodiester bond formation between compatible ends. | Essential for all ligation-based cloning. Requires ATP [20]. |

| Competent E. coli Cells | Propagation and amplification of assembled plasmid DNA after transformation. | High transformation efficiency (>10⁷ CFU/µg) is crucial for obtaining sufficient clones, especially for large constructs. |

| DNA Purification Kits | Removal of enzymes, salts, and other impurities post-digestion or from PCR products. | Clean DNA is vital for efficient downstream enzymatic reactions. |

| Golden Gate-Compatible Vectors (e.g., pGGAselect) | Plasmid backbones containing the required Type IIS sites for part excision and assembly. | Must be free of internal recognition sites for the enzyme used [20]. |

| BglBrick-Compatible Vectors (e.g., pBb series) | Standardized plasmids with BglII/BamHI sites for part insertion and characterized origins/promoters. | Datasheets with quantitative expression data are available for many vectors [19]. |

The historical development from BioBrick to BglBrick and Golden Gate standards mirrors synthetic biology's journey toward greater precision, complexity, and efficiency. The choice of assembly standard is not merely a technical decision but a strategic one that influences experimental design, timeline, and outcome. BioBricks established the critical principle of part standardization. BglBricks advanced the field by enabling reliable protein fusion construction, which is vital for metabolic and protein engineering. Golden Gate assembly has set a new benchmark with its scarless, one-pot, highly efficient methodology, making it the current system of choice for complex projects. For researchers and drug developers, this comparative analysis underscores that while older standards retain historical and educational value, modern methodologies like Golden Gate and its standardized toolkits offer the most powerful and flexible platform for driving innovation in genetic engineering and therapeutic development.

In synthetic biology, the assembly of genetic circuits relies on standardized methods that dictate the final structure and function of the constructed DNA. A critical differentiator among these methods is the presence and size of nucleotide "scars"—short extraneous sequences left at the junctions between assembled DNA parts. The choice between Type IIP and Type IIS restriction enzymes is the primary technical factor determining scar formation [23] [24]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of three common assembly standards—BioBrick, BglBrick, and Golden Gate—focusing on their use of restriction enzymes and the resulting scar sequences, to inform decision-making for research and drug development.

Comparative Analysis of Assembly Standards

The table below summarizes the key technical specifications of the three major assembly standards, highlighting the direct relationship between enzyme choice and scar properties.

Table 1: Technical Comparison of DNA Assembly Standards

| Feature | BioBrick (RFC 10) | BglBrick (RFC 21) | Golden Gate (e.g., RFC 1000) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Restriction Enzymes | EcoRI, XbaI, SpeI, PstI [25] | EcoRI, BglII, BamHI, XhoI [25] | Type IIS (e.g., BsaI, BsmBI) [23] [26] |

| Enzyme Type | Type IIP [24] | Type IIP [24] | Type IIS [23] [24] |

| Scar Sequence | TACTAGAG or TACTAG [25] | GGATCT [25] | Scarless (by design) [23] |

| Scar Length | 8 bp or 6 bp [25] | 6 bp [25] | 0 bp [23] |

| In-Frame Fusion Capability | Not possible with main standard; requires modified standards [25] | Yes, encodes Gly-Ser [25] | Yes, seamless and scarless [23] |

| Typical Assembly Efficiency | Sequential, one part per reaction | Sequential, one part per reaction | High; allows for simultaneous, modular assembly of many fragments [14] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Standards

BioBrick/BglBrick Standard 3A Assembly

The "3A Assembly" process is a sequential method for combining DNA parts [26].

- Digestion: Digest both the insert and the backbone plasmid with the two restriction enzymes that define the prefix and suffix (e.g., EcoRI and XbaI for the insert, EcoRI and SpeI for the backbone in BioBrick) [25].

- Purification: Purify the digested DNA fragments to remove enzymes and buffers.

- Ligation: Mix the compatible ends of the insert and backbone DNA using T4 DNA ligase. The SpeI and XbaI sites on the backbone and insert create a hybrid scar sequence that cannot be re-cut by either enzyme [25].

- Transformation: Introduce the ligated product into competent E. coli cells.

- Screening: Select for transformed colonies and verify the correct assembly by colony PCR or diagnostic restriction digest.

Golden Gate Assembly

Golden Gate assembly utilizes Type IIS enzymes to enable one-pot, scarless assembly [23] [14].

- Vector and Insert Design: Clone DNA parts into a vector or design PCR primers so that Type IIS recognition sites (e.g., BsaI sites) flank the parts. The sites must be oriented such that cleavage occurs inward for inserts and outward for the destination vector [23].

- One-Pot Reaction: Set up a single-tube reaction containing:

- Cyclic Digestion and Ligation: Subject the reaction to cycles of digestion and ligation (e.g., 25-37°C for 5 minutes, then 16-20°C for 5 minutes, repeated 25-50 times). The restriction enzyme continually cleaves away the original recognition sites, while the ligase joins the complementary overhangs. Correctly assembled products lack the recognition sites and are thus protected from re-digestion [23] [14].

- Transformation and Verification: Transform the final assembly mixture into competent cells and screen for correct clones.

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and molecular logic of Golden Gate assembly.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of DNA assembly standards requires a suite of reliable reagents and tools. The following table details essential components for experiments featured in this guide.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DNA Assembly

| Reagent/Kit | Function/Description | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Type IIP Restriction Enzymes (e.g., EcoRI, SpeI) [25] | Cleave within their palindromic recognition sites to generate specific ends for traditional assembly. | Well-characterized, simple to use, ideal for sequential assembly. |

| Type IIS Restriction Enzymes (e.g., BsaI-HFv2, BsmBI-v2) [23] [27] [24] | Cleave outside their asymmetric recognition sites to generate custom overhangs. | Enables scarless, one-pot assembly of multiple fragments (Golden Gate). |

| T4 DNA Ligase [26] | Joins DNA fragments by catalyzing the formation of phosphodiester bonds. | Essential for sealing nicks in the DNA backbone during and after restriction enzyme digestion. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (e.g., Q5) [26] | Amplifies DNA fragments with very low error rates for PCR-based assembly preparation. | Critical for generating accurate inserts without mutations. |

| Golden Gate Assembly Kits (NEB, Thermo Fisher) [23] [26] | Provide pre-optimized mixes of Type IIS enzymes and ligase in a single buffer. | Maximizes convenience and efficiency for one-pot Golden Gate reactions. |

| Competent E. coli Cells (e.g., DH5-alpha, NEB 5-alpha) [26] | Used for transforming assembled DNA plasmids after ligation. | High transformation efficiency is crucial for obtaining correct clones. |

The choice of a DNA assembly standard involves a direct trade-off between simplicity and precision. BioBrick and BglBrick standards, reliant on Type IIP enzymes, are straightforward but inevitably leave behind nucleotide scars that can interfere with protein function and complex circuit design [25]. In contrast, the Golden Gate standard, powered by Type IIS enzymes, enables scarless and seamless assembly of multiple DNA fragments in a single reaction [23] [14]. For research and drug development applications where the precise sequence and function of proteins or regulatory elements are paramount—such as in gene therapy or metabolic engineering—Golden Gate assembly with Type IIS enzymes presents a superior and more flexible technical specification.

From Theory to Bench: Practical Applications and Workflows for Each Standard

Step-by-Step BioBrick Assembly Protocol and Iterative Construction

The engineering of biological systems demands a level of precision and predictability akin to traditional engineering disciplines. This need has driven the development of standardized DNA assembly methods, which provide the foundational tools for synthetic biology. Among the earliest and most influential standards is the BioBrick assembly standard, which established a framework for treating DNA sequences as reusable, interoperable parts [28]. This review provides a comparative analysis of three significant assembly standards: the foundational BioBrick system, the protein-fusion-optimized BglBrick standard, and the highly efficient Golden Gate method. We will dissect their core mechanisms, provide step-by-step protocols, and present experimental data to compare their performance, efficiency, and suitability for different applications in research and drug development.

Assembly Standards: A Comparative Framework

Core Principles and Historical Context

- BioBrick (BBF RFC 10): Developed in 2002, the BioBrick standard was the first to implement an idempotent assembly strategy, where any two BioBrick parts can be combined to create a new composite part that is itself a BioBrick part [28]. This supports hierarchical, iterative assembly. The standard uses prefix and suffix sequences flanking the genetic part, encoding EcoRI/XbaI and SpeI/PstI restriction sites, respectively [28].

- BglBrick: Created to address a major limitation of the original BioBrick standard, BglBrick enables the construction of protein fusions [8]. It uses BglII and BamHI restriction enzymes, which produce a 6-nucleotide scar sequence (GGATCT) that translates into a glycine-serine peptide linker, an innocuous amino acid sequence in most protein fusion applications [8].

- Golden Gate: This method utilizes Type IIS restriction enzymes, which cleave DNA outside of their recognition site [18]. This allows for the seamless assembly of multiple DNA fragments in a single reaction, as the cleavage leaves behind user-defined, complementary overhangs. Variations like Golden EGG further simplify the process by using a single Type IIS enzyme for both entry clone construction and multi-fragment assembly [18].

Comparative Analysis of Key Characteristics

Table 1: Direct comparison of the three DNA assembly standards.

| Feature | BioBrick (BBF RFC 10) | BglBrick | Golden Gate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Restriction Enzymes | EcoRI, XbaI, SpeI, PstI [28] | BglII, BamHI [8] | Type IIS (e.g., BsaI, BbsI, SapI) [18] [29] |

| Scar Sequence | 8 bp (TACTAGAG) [28] | 6 bp (GGATCT) [8] | Seamless (0 bp) [18] |

| Scar Translation | Tyrosine-STOP codon [8] | Glycine-Serine [8] | N/A (seamless) or designed |

| Assembly Type | Iterative, pairwise | Iterative, pairwise | One-pot, multi-fragment |

| Key Advantage | Established, idempotent system | Compatible with protein fusions | High efficiency, multi-fragment assembly |

| Primary Limitation | Scar incompatible with protein coding; slow iterative process | Iterative process can be slow | Requires careful design of overhangs |

Detailed Step-by-Step Protocols

BioBrick Assembly Using the Three Antibiotic (3A) Method

The 3A assembly method is a robust BioBrick protocol that uses positive and negative selection to enhance the proportion of correct clones [28].

- Digestion: In separate reactions, digest the upstream part plasmid with EcoRI-HF and SpeI, the downstream part plasmid with XbaI and PstI, and the destination vector with EcoRI-HF and PstI. The destination vector must have a different antibiotic resistance marker than the part plasmids [28].

- Ligation: Combine the digested upstream part, downstream part, and destination vector in a single ligation reaction without purification. The variety of fragments allows for multiple ligation products, but selection will isolate the correct one [28].

- Transformation: Transform the ligation reaction into competent E. coli cells and plate onto media containing the antibiotic corresponding to the destination vector.

- Selection & Verification: Correct clones will be resistant to the destination vector's antibiotic and sensitive to the antibiotics of the two part vectors. Correct assembly is typically verified by colony PCR and agarose gel electrophoresis to check the insert size, with reported success rates often exceeding 80% [28].

Figure 1: Workflow for BioBrick 3A Assembly. The process involves digesting three separate plasmids, ligating the fragments, and selecting for the correct product using antibiotic resistance and sensitivity.

BglBrick Assembly

The BglBrick standard is designed for flexibility and protein fusions. While multiple assembly methods are possible, a core restriction-based protocol is as follows.

- Digestion: Digest the upstream part (Part A) with BamHI. This cuts at the 3' end of the part. Digest the downstream part (Part B) with BglII. This cuts at the 5' end of the part. The vector backbone is digested with both BamHI and BglII [8].

- Ligation: Ligate the BamHI-digested Part A with the BglII-digested Part B into the doubly-digested vector. BglII and BamHI generate compatible cohesive ends that ligate together.

- Formation of Scar: The ligation between Part A and Part B creates a 6-bp scar sequence (GGATCT) that is not recognized by either BglII or BamHI. The resulting composite part is flanked by the original BglII (5') and BamHI (3') sites, making it a new BglBrick part that can be used in further assemblies [8].

Golden Gate Assembly

Golden Gate assembly, particularly the simplified Golden EGG method, allows for efficient one-pot assembly of multiple fragments [18].

- PCR Amplification or Entry Clone Preparation: DNA fragments are PCR-amplified with primers containing the appropriate Type IIS enzyme recognition sites (e.g., BsaI for Golden EGG) and the desired 4-nt overhangs, or they are pre-cloned in a universal entry vector like pEGG [18].

- Single-Pot Digestion-Ligation: Combine all DNA fragments (entry clones or PCR products) and the destination vector in a single tube with the Type IIS restriction enzyme (e.g., BsaI-HFv2) and a DNA ligase (e.g., T4 DNA ligase). The NEBridge Ligase Master Mix is specifically formulated for this purpose [29].

- Thermocycling: Run the reaction in a thermocycler. A typical protocol for 3-6 fragments involves 30 cycles of (37°C for 1 minute + 16°C for 1 minute), followed by 60°C for 5 minutes and a 4°C hold [29]. The cycling repeatedly digests incorrectly ligated products and re-ligates the fragments, driving the reaction toward the correct assembly.

- Transformation: Transform the final reaction mixture into competent E. coli cells. The correct assembled product lacks the restriction site and is thus stable, leading to a high percentage of correct clones.

Performance and Experimental Data Comparison

Quantitative Metrics of Assembly Performance

Table 2: Experimental performance data for different assembly standards.

| Standard | Typical Efficiency (Correct Clones) | Fragments per Reaction | Typical Scar Size | Notable Burdens/Constraints |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BioBrick (3A) | >80% [28] | 2 (iterative) | 8 bp [28] | Plasmid burden can reduce host growth rate by up to 45% [30] |

| BglBrick | Not explicitly quantified | 2 (iterative) | 6 bp [8] | Specific burden data not provided in results. |

| Golden Gate | High (often >90%) | 6+ in a single pot [18] [29] | 0 bp (seamless) [18] | Simpler design and higher efficiency reduces experimental burden. |

Evolutionary Stability and Cellular Burden

A critical factor in synthetic biology is the "burden" that engineered DNA places on the host cell, which can drive the evolution of non-functional escape mutants. A study measuring the burden of 301 BioBrick plasmids in E. coli found that 19.6% significantly slowed host growth, primarily by depleting gene expression resources [30]. The most burdensome plasmids reduced growth rates by over 30%, a level that makes constructs highly unstable on a laboratory scale. No BioBrick construct reduced the growth rate by more than 45%, which aligns with a population genetic model predicting this as an upper limit for clonability [30]. This highlights a fundamental constraint for all DNA assembly methods: the encoded function must not overwhelm the host's cellular machinery.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key reagents and materials required for implementing DNA assembly protocols.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Assembly | Example Products / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Type IIP Restriction Enzymes | Cuts within recognition site to generate specific ends for BioBrick/BglBrick. | EcoRI, XbaI, SpeI, PstI (for BioBrick) [28]; BglII, BamHI (for BglBrick) [8] |

| Type IIS Restriction Enzymes | Cuts outside recognition site to create custom overhangs for Golden Gate. | BsaI-HFv2, SapI, BbsI [18] [29] |

| DNA Ligase | Joins DNA fragments with compatible ends. | T4 DNA Ligase; NEBridge Ligase Master Mix [29] |

| Destination Vectors | Backbone plasmid for assembling and propagating constructs. | pSB1A3, pSB1K3 (BioBrick) [28]; pEGG vectors (Golden EGG) [18] |

| Chemically Competent E. coli | For plasmid transformation after ligation. | High-efficiency cells (>10^8 CFU/μg) recommended for 3A assembly [28] |

| Selection Antibiotics | Selects for bacteria containing the assembled plasmid. | Ampicillin, Kanamycin, Chloramphenicol (used in 3A assembly) [28] |

| ccdB Toxin Gene | Negative selection marker to counter-select against empty destination vectors. | Found in BioBrick and Golden EGG destination vectors [28] [18] |

The choice of a DNA assembly standard is a fundamental decision in any synthetic biology project. The BioBrick standard established the principle of standardized, hierarchical biological part assembly and remains a valuable educational tool. The BglBrick standard successfully addressed the critical need for in-frame protein fusions within a similar idempotent framework. However, the Golden Gate method, with its one-pot, multi-fragment capability and seamless results, represents a significant advance in efficiency and flexibility for constructing complex systems.

For researchers and drug development professionals, this comparative analysis suggests that while historical context is important, modern projects demanding high-throughput, complex circuit assembly, or precise protein engineering will benefit greatly from adopting Golden Gate or its simplified derivatives like Golden EGG. The limiting factor for all these methods is not just the assembly chemistry itself, but also the biological compatibility of the engineered DNA with the host cell, as underscored by burden studies [30]. As the field progresses, integration of these standardized assembly methods with automation and robust computational design tools will continue to transform genetic engineering into a more predictable and powerful discipline.

The field of synthetic biology is grounded in the principle of standardization, which enables the reliable construction of complex genetic systems from interchangeable DNA parts. Among the various assembly standards developed, the BglBrick standard occupies a critical niche, particularly for applications requiring the creation of functional fusion proteins. This methodology addresses a fundamental limitation of the original BioBrick assembly system by enabling the seamless fusion of protein-coding sequences through the strategic design of peptide linkers [8]. The core innovation of the BglBrick system lies in its generation of a defined glycine-serine linker between joined protein domains, a feature that has proven exceptionally valuable for protein engineers [8] [31].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of the BglBrick methodology against other prominent DNA assembly standards, with a specific focus on its application in designing glycine-serine linkers for protein engineering. We present experimental data quantifying linker properties, detailed protocols for implementation, and a objective assessment of performance relative to alternative systems. For researchers developing multidomain proteins—including therapeutic antibodies, biosensors, and enzymatic cascades—understanding the capabilities and limitations of the BglBrick approach is essential for selecting the appropriate assembly strategy for their specific application.

Comparative Analysis of DNA Assembly Standards

The evolution of DNA assembly standards reflects the synthetic biology community's ongoing effort to balance simplicity, reliability, and functional utility. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of three principal standards.

Table 1: Comparison of Major DNA Assembly Standards

| Feature | BioBrick (RFC 10) | BglBrick (RFC 21) | Golden Gate (e.g., RFC 1000) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Restriction Enzymes Used | XbaI & SpeI | BglII & BamHI | Type IIS (e.g., BsaI, BsmBI) |

| Scar Sequence Length | 8 nucleotides | 6 nucleotides | Typically scarless |

| Translated Scar Sequence | TACTAGAG (Tyrosine-Stop) | GGATCT (Glycine-Serine) | Varies; often designed to be scarless |

| Suitability for Protein Fusions | Poor (contains stop codon) | Excellent (neutral linker) | Excellent (precise design possible) |

| Primary Application Focus | Genetic circuit assembly | Protein fusion construction | Modular, high-throughput assembly |

| Automation Compatibility | Moderate | High (e.g., with 2ab assembly) | High |

The original BioBrick standard (BBF RFC 10) pioneered the concept of standardized biological parts but was fundamentally limited for protein engineering. The 8-nucleotide scar sequence it produces encodes a tyrosine followed by a stop codon, which prevents the translation of downstream protein domains [8]. The Golden Gate assembly system, which uses Type IIS restriction enzymes that cut outside their recognition sites, offers tremendous flexibility. It enables the creation of virtually any junction sequence, including scarless fusions, and supports highly modular, parallel assembly strategies [26]. However, this flexibility often requires custom primer design for each part, potentially increasing cost and complexity [26].

The BglBrick standard strikes a balance between these approaches. It uses the robust restriction enzymes BglII and BamHI, which generate compatible cohesive ends. Their ligation creates a 6-nucleotide "scar" (GGATCT) that, when translated, produces a glycine-serine dipeptide [8] [31]. This specific amino acid sequence is widely recognized as a flexible, innocuous linker that minimally interferes with the structure and function of fused protein domains, making the standard particularly well-suited for constructing chimeric proteins [8] [32].

The Science of Glycine-Serine Linkers in Protein Engineering

Biochemical Properties and Rationale

Linkers in fusion proteins serve as structural spacers that connect functional domains. Their optimal design is critical for maintaining the stability, activity, and correct folding of the constituent domains. Glycine and serine residues are favored in linker design due to their unique biochemical properties. Glycine, with its single hydrogen atom side chain, confers exceptional flexibility because of its low steric hindrance and ability to adopt a wide range of dihedral angles. Serine enhances solubility and prevents unwanted aggregation due to its hydrophilic nature [32]. The Gly-Ser dipeptide encoded by the BglBrick scar is a naturally occurring and well-tolerated motif in recombinant fusion proteins, often functioning as a minimal flexible linker [8] [32].

Quantitative Analysis of Linker Flexibility and Length

The conformational properties of glycine-serine linkers can be systematically tuned and quantitatively understood. Research using Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) between ECFP and EYFP fluorescent proteins connected by various Gly/Ser linkers has provided experimental data on how linker composition affects flexibility.

Table 2: Effect of Linker Composition on Flexibility and Stiffness

| Linker Repeat Sequence | Glycine Content | Persistence Length (Å) | Relative Stiffness |

|---|---|---|---|

| GGS (Gly-Gly-Ser) | 67% | 4.5 Å | Most Flexible |

| GSSGSS | 33.3% | 4.8 Å | Intermediate |

| GSSSSS | 16.7% | 5.1 Å | Intermediate |

| SSSSSS (Ser-only) | 0% | 6.2 Å | Stiffest |

The data demonstrates a direct correlation between glycine content and linker flexibility. A higher glycine content results in a shorter persistence length, a biophysical parameter indicating increased flexibility [33] [34]. This tunability is a powerful feature for protein engineers. For instance, flexible GGS linkers are ideal for connecting domains that require a high degree of conformational freedom, while stiffer, serine-rich linkers are better suited for maintaining a fixed separation between domains or for applications where a higher effective local concentration of the connected domains is desired [33].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between linker design, its biophysical properties, and the resulting functional outcomes in engineered proteins.

Experimental Protocols for BglBrick Assembly and Characterization

Standard BglBrick Assembly Workflow

The physical assembly of BglBrick parts can be achieved through several methods, with the core principle relying on the complementary cohesive ends generated by BglII and BamHI digestion.

- Vector and Part Preparation: A BglBrick plasmid is defined as a vector backbone with a part inserted between the BglII (5') and BamHI (3') sites. The vector itself is flanked by EcoRI and XhoI sites for broader manipulation [8] [19].

- Restriction Digest: To join two parts (A and B), the donor plasmid containing part A is digested with BamHI. This enzyme cuts after the part sequence. The acceptor plasmid (or vector) containing part B is digested with BglII, which cuts before the part sequence.

- Ligation and Transformation: The digested fragments are ligated. The compatible ends of BamHI (GATC) and BglII (GATC) facilitate the ligation, creating a new composite part where A and B are separated by the 6-bp scar sequence GGATCT. This ligation mixture is then transformed into a suitable E. coli host [8] [31].

- Selection and Verification: Transformed cells are selected using the appropriate antibiotic. The successful assembly results in a new composite part that is functionally equivalent to a basic part—it is flanked by BglII and BamHI sites and can be used in further rounds of iterative assembly [8].

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key steps in the BglBrick assembly process.

Advanced Automated Assembly: The 2ab System

To enable high-throughput, automated assembly of BglBricks, the 2ab assembly system was developed. This method uses a set of specialized vectors containing two antibiotic resistance genes (chosen from ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and kanamycin) separated by an XhoI site [31].

- Methylation Protection: Prior to assembly, "lefty" parts are protected from BglII digestion by transforming them into an E. coli strain that methylates BglII sites. Similarly, "righty" parts are protected from BamHI digestion in a BamHI-methylating strain [31].

- Digestion and Ligation: The protected plasmids are combined and digested with a cocktail of BglII, BamHI, and XhoI. The methylation prevents digestion at the designated sites, ensuring directional assembly. The ligation creates new plasmid architectures [31].

- Selection of Products: The use of vectors with different antibiotic resistance combinations allows for the direct selection of the desired ligation product on plates containing specific antibiotic pairs, eliminating the need for gel purification. This makes the process highly amenable to automation using liquid handling robots [31].

Protocol for Characterizing Linker Flexibility

The flexibility of glycine-serine linkers of different compositions can be quantitatively characterized using FRET, as referenced in Table 2.

- Construct Design: Genetically fuse the cyan fluorescent protein (ECFP) and the yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) with the glycine-serine linker of interest (e.g., (GSSGSS)~n~, (GSSSSS)~n~, (SSSSSS)~n~) inserted between them [33] [34].

- Protein Expression and Purification: Clone the fusion constructs into an expression vector (e.g., pET-28a(+)). Express the proteins in E. coli BL21(DE3) and purify them using affinity chromatography (e.g., Ni-NTA for His-tagged proteins) followed by size exclusion chromatography if necessary [33].

- Fluorescence Spectroscopy: Dilute the purified proteins to a standardized concentration (e.g., 200 nM) in a suitable buffer. Record the fluorescence emission spectrum of each construct using an excitation wavelength of 420 nm.

- FRET Efficiency Calculation: The FRET efficiency (E) can be calculated from the relative emission intensities of the acceptor (EYFP) and donor (ECFP). A common method is using the acceptor-sensitized emission: E = I~A~/(I~A~ + γI~D~), where I~A~ is the acceptor fluorescence intensity and I~D~ is the donor fluorescence intensity, with γ being an instrument-specific correction factor [33].

- Data Modeling: Fit the experimentally determined FRET efficiencies to theoretical models such as the Wormlike Chain (WLC) model to extract the persistence length, which serves as a quantitative measure of linker stiffness [33] [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for BglBrick Assembly and Linker Analysis

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Sources / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| BglII Restriction Enzyme | Cuts 5' to part (A^GATCT) to generate compatible end. | New England Biolabs, Thermo Fisher |

| BamHI Restriction Enzyme | Cuts 3' to part (G^GATCC) to generate compatible end. | New England Biolabs, Thermo Fisher |

| BglBrick-Compatible Vectors | Plasmids with orthogonal replication origins and markers. | pBb series vectors [19] |

| 2ab Assembly Vectors | Specialized vectors for automated assembly (e.g., AC, CK, KA). | Anderson Lab collection [31] |

| Methylation Strains | E. coli strains for protecting BglII or BamHI sites. | Specialized lab strains [31] |

| Fluorescent Protein Plasmids | ECFP and EYFP for FRET-based linker analysis. | Available from addgene.org |

| pNBBX Vector | Modified BglBrick vector for use in Lactococcus lactis. | Example of system adaptation [12] |

Performance and Limitations in Practical Applications

Documented Successes and Metabolic Burden

The BglBrick standard has been successfully employed in diverse applications. It has been used to build libraries of constitutive gene expression devices with varying strengths, construct functional chimeric proteins, and integrate DNA sequences into specific genomic loci [8]. A key consideration in any engineered genetic system is the metabolic burden imposed on the host cell. A large-scale study measuring the burden of 301 BioBrick plasmids found that 19.6% significantly reduced the growth rate of E. coli [30]. This burden often arises from the depletion of limited cellular resources like ribosomes and RNA polymerases. The study established an apparent evolutionary limit, with no natural plasmids reducing growth rate by more than 45%, as more burdensome constructs are rapidly outcompeted by "escape mutant" cells [30]. This underscores the importance of considering host physiology when expressing BglBrick-assembled constructs, especially multi-domain proteins.

Known Limitations and Strategic Workarounds

- Fixed Scar Sequence: The primary limitation of the BglBrick system is the fixed glycine-serine scar. While beneficial in many contexts, it may not be optimal for all protein fusions. Some domains might require a more rigid spacer or a specific amino acid sequence for proper folding or activity [8].

- Alternative Standards: For these specific cases, Golden Gate assembly is a superior alternative. Its ability to create virtually any junction sequence allows for the custom design of linker peptides, providing maximum flexibility for challenging fusions [26].

- Restriction Site Conflicts: The presence of internal BglII, BamHI, EcoRI, or XhoI sites within a part's sequence prevents standard assembly. This can be resolved by using silent mutagenesis to remove the internal restriction sites before designating the part as a standard BglBrick [8] [31].

- System Adaptation: The standard has been successfully adapted for use in other organisms beyond E. coli. For example, a modified BglBrick system was implemented in Lactococcus lactis by replacing BamHI with BclI (which creates a compatible overhang) to circumvent the prevalence of BamHI sites in native L. lactis plasmids [12].

The BglBrick methodology remains a robust, reliable, and well-characterized standard for the assembly of genetic parts, with its signature strength being the straightforward construction of fusion proteins joined by flexible glycine-serine linkers. Its compatibility with automation platforms like 2ab assembly enhances its utility for high-throughput projects. The quantitative understanding of Gly-Ser linker flexibility provides a rational basis for designing multidomain proteins.

The choice of an assembly standard is, and should be, application-dependent. For the construction of genetic circuits where protein fusions are not required, the original BioBrick standard or Golden Gate may be suitable. However, for metabolic engineering pathways requiring multi-enzyme complexes, or for the development of therapeutic fusion proteins and biosensors, the BglBrick standard offers a compelling combination of simplicity and proven performance. As the field of synthetic biology continues to advance, the principles of standardization and rational linker design embodied by the BglBrick system will continue to be foundational to the engineering of increasingly sophisticated biological systems.

The field of synthetic biology has been revolutionized by standardized DNA assembly methods that enable the reproducible and efficient construction of genetic circuits. The progression from early assembly standards like BioBrick and BglBrick to modern Golden Gate systems represents a fundamental shift toward higher efficiency, flexibility, and scalability in genetic engineering [8] [5]. This evolution addresses critical limitations in traditional cloning, particularly the constraints of type II restriction enzymes that cut within their recognition sites, leaving unwanted "scar" sequences between assembled parts [35] [36]. The Golden Gate protocol, utilizing Type IIS restriction enzymes such as BsaI that cut outside their recognition sequences, enables seamless, one-pot assembly of multiple DNA fragments without residual sequences [37] [38]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this technological progression is essential for selecting optimal cloning strategies for pathway engineering, therapeutic development, and genetic circuit design.

Comparative Analysis of DNA Assembly Standards

Historical Context: BioBrick and BglBrick Foundations

The BioBrick standard (BBF RFC 10) pioneered the concept of standardized biological parts through iterative assembly using restriction enzymes EcoRI, XbaI, SpeI, and PstI [9] [8]. While revolutionary for its idempotent assembly principle (where two assembled parts form a new composite part with the same format), BioBrick suffered from significant limitations: (1) an 8-bp scar sequence (TACTAGAG) that encoded a stop codon, making it unsuitable for protein fusions; (2) relatively slow assembly, joining only two parts per cycle; and (3) methylation sensitivity (XbaI sites could be blocked by dam methylation) [9] [8].

The BglBrick standard addressed several BioBrick limitations by employing BglII and BamHI restriction enzymes, which generated a 6-bp scar (GGATCT) encoding glycine-serine—a benign peptide linker suitable for protein fusions in various host systems [8]. BglBrick advantages included: (1) use of robust, methylation-insensitive enzymes; (2) a scar sequence compatible with protein fusion applications; and (3) maintenance of the idempotent assembly principle [8]. However, like BioBricks, BglBrick remained limited to two-part assemblies per cycle, restricting its throughput for complex constructs.

The Golden Gate Revolution: Principles and Advantages

Golden Gate assembly represents a paradigm shift from these earlier standards by harnessing Type IIS restriction enzymes (e.g., BsaI, BsmBI, BpiI) that cleave DNA outside their recognition sequences [37] [38]. This fundamental mechanistic difference enables several key advantages:

- Seamless assembly: No scar sequences remain between assembled fragments [38]

- Multi-part, one-pot assembly: Up to 50+ fragments can be assembled in a single reaction with >90% accuracy [37]

- Hierarchical capability: Standardized systems like MoClo and Golden Braid enable endless assembly through predefined levels [39] [5]

- Standardized part repositories: Community-shared parts reduce costs and accelerate high-throughput projects [39]

The core Golden Gate mechanism involves designing DNA parts with Type IIS recognition sites flanking the sequence such that digestion produces user-defined 4-base overhangs [38]. These customized overhangs direct the ordered assembly of multiple fragments in a single-tube reaction containing both the Type IIS enzyme and DNA ligase [38].

Table 1: Comparison of DNA Assembly Standards

| Feature | BioBrick | BglBrick | Golden Gate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key Enzymes | EcoRI, XbaI, SpeI, PstI | BglII, BamHI | BsaI, BsmBI, BpiI (Type IIS) |

| Scar Size | 8 bp | 6 bp | Scarless |

| Scar Sequence | TACTAGAG | GGATCT | None |

| Scar Translation | Tyrosine + STOP | Glycine-Serine | None |

| Assembly Speed | Slow (2 parts/cycle) | Slow (2 parts/cycle) | Rapid (up to 50+ parts/cycle) |

| Protein Fusion Compatible | No | Yes | Yes |

| Multi-part Assembly | No | No | Yes |

| Methylation Sensitivity | Yes (XbaI) | No | Varies by enzyme |

Golden Gate Experimental Framework: Protocols and Reagents

Core Reaction Mechanism and Workflow

The Golden Gate protocol employs a unique cycling process that alternates between digestion and ligation, progressively driving the reaction toward complete assembly [38] [40]. When properly designed, the Type IIS restriction site is eliminated from the final assembled construct, making the reaction irreversible [38]. Recent advances in understanding ligase fidelity have enabled more predictable assembly of complex constructs by identifying overhang sequences with improved assembly accuracy [37].

The following diagram illustrates the core experimental workflow for a standard Golden Gate assembly:

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Reaction Setup and Conditions

Based on established laboratory protocols [40], the Golden Gate assembly reaction is prepared as follows: