A Practical Framework for Validating Synthetic Data in Computational Biology Benchmarks

The adoption of synthetic data in computational biology is accelerating, offering solutions to data scarcity, privacy constraints, and the need for robust benchmark studies.

A Practical Framework for Validating Synthetic Data in Computational Biology Benchmarks

Abstract

The adoption of synthetic data in computational biology is accelerating, offering solutions to data scarcity, privacy constraints, and the need for robust benchmark studies. However, its utility is entirely contingent on rigorous, domain-specific validation. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles, methodological applications, and practical tools for synthetic data validation. We explore the '7 Cs' evaluation criteria, detail statistical and machine learning validation techniques, and present best practices for troubleshooting and optimization. By synthesizing the latest research and tools, this guide empowers scientists to build confidence in synthetic datasets, ensuring their reliability for benchmarking differential abundance tests, training predictive models, and advancing biomedical discovery.

Why Validation is Critical: The Foundation of Trust in Synthetic Biological Data

The Promise and Peril of Synthetic Data in Computational Biology

Synthetic data, or artificially generated information created by algorithms to mimic the statistical properties of real-world datasets, is rapidly transforming computational biology [1]. This innovative approach promises to overcome significant hurdles in biological research, including data scarcity, privacy concerns, and the high cost of data acquisition [2] [3]. As the field grapples with an explosion of computational methods—with single-cell RNA-sequencing tools alone exceeding 1,500—the role of synthetic data in benchmarking and validation has become increasingly critical [4].

The promise is substantial: synthetic data can accelerate research timelines from weeks to minutes, enable privacy-preserving collaboration, and provide limitless material for training AI models [5] [2]. Yet significant perils accompany this potential. Concerns about data quality, algorithmic bias, model collapse, and the preservation of subtle biological nuances present substantial challenges [6] [2]. This comparison guide examines the current state of synthetic data validation in computational biology through the lens of recent experimental studies, providing researchers with objective performance assessments and methodological frameworks for responsible implementation.

Performance Comparison: Synthetic Data in Biological Applications

Rigorous benchmarking studies provide crucial insights into how synthetic data performs across biological applications. The table below summarizes key performance findings from recent research:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Synthetic Data in Biological Applications

| Application Area | Model/Technique | Performance Outcome | Key Metrics | Comparative Baseline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiology Reporting (Free text to structured data) | Yi-34B (synthetic data-trained) | No significant difference from GPT-4 5-shot (0.95 vs 0.97, p=1) [7] | F1 score for field name and value matching | GPT-4 5-shot (proprietary model) |

| Radiology Reporting (Free text to structured data) | Open-source models (1B-13B parameters) | Outperformed GPT-3.5 5-shot (0.82-0.95 vs 0.80) [7] | F1 score for template completion | GPT-3.5 5-shot (proprietary model) |

| LLM Biological Knowledge | Frontier LLMs (2022-2025) | 4-fold improvement on Virology Capabilities Test; some models exceed expert virologists [8] | Accuracy on specialized biology benchmarks | Human expert performance |

| Synthetic Data Generation (General) | YData synthetic data generator | Top statistical accuracy in AIMultiple's 2025 benchmark [9] | Correlation distance (Δ), Kolmogorov-Smirnov distance (K), Total Variation Distance (TVD) | Seven publicly available synthetic data generators |

The performance evidence indicates that synthetic data can achieve remarkably competitive results against both proprietary AI systems and human experts in specific biological domains. In radiology reporting, open-source models fine-tuned with synthetic data not only matched but exceeded the performance of leading proprietary models while offering privacy preservation advantages [7]. The dramatic improvements in biological knowledge demonstrated by LLMs further highlight the potential of synthetic approaches to augment expert capabilities [8].

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

Protocol 1: Radiology Reporting with Synthetic Data

A 2025 study published in npj Digital Medicine established a comprehensive protocol for evaluating synthetic data in radiology applications [7]:

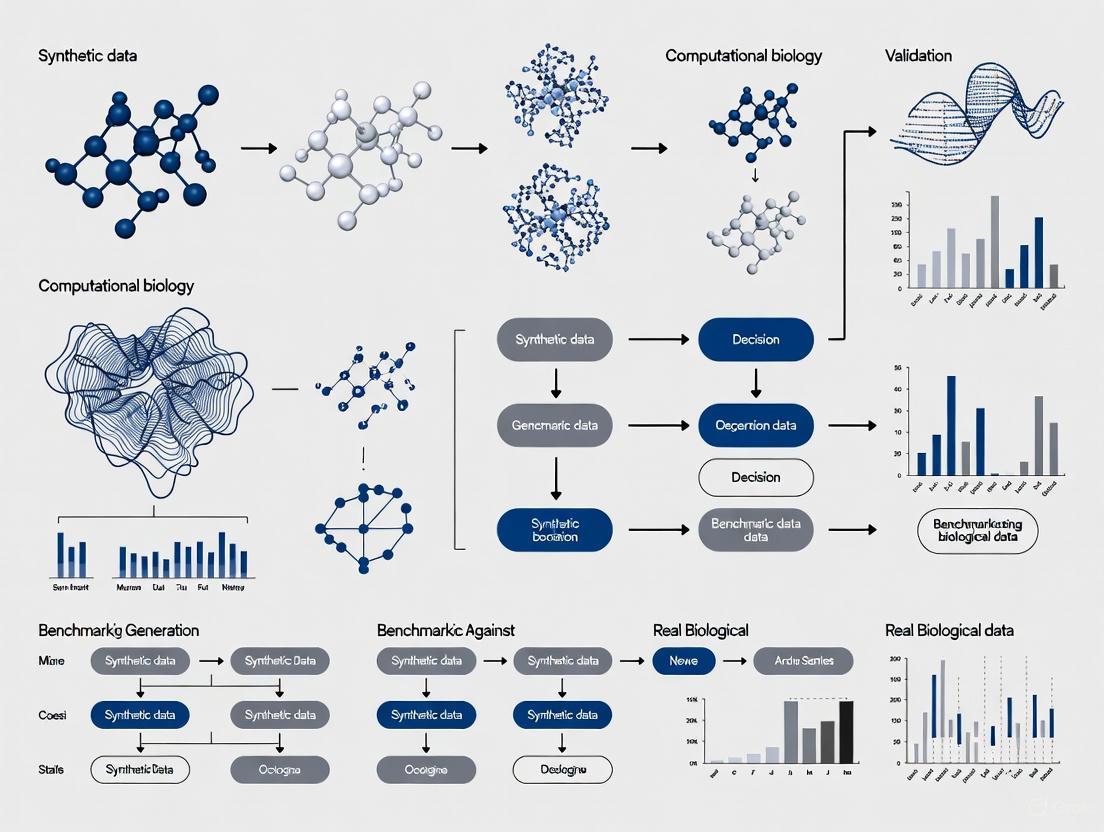

Figure 1: Synthetic Data Training Workflow for Radiology Reporting

Methodology Details:

- Synthetic Data Generation: Created 3,000 synthetic thyroid nodule dictations with variations in length (23-44 words) and clinical characteristics

- Model Training: Fine-tuned six open-source models (Starcoderbase-1B/3B, Mistral-7B, Llama-3-8B, Llama-2-13B, Yi-34B) using synthetic data

- Validation Approach: Employed "Train on Synthetic, Test on Real" (TSTR) methodology using 50 real thyroid nodule dictations from the MIMIC-III patient dataset

- Evaluation Metrics: Precision, recall, and F1 scores for both field names and values in ACR TI-RADS template completion

- Comparative Baseline: Compared performance against GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 with 0-shot, 1-shot, and 5-shot prompting [7]

Protocol 2: Comprehensive Benchmarking for Single-Cell Analysis

A systematic evaluation of 282 single-cell benchmarking papers established rigorous protocols for synthetic data validation in computational biology [4]:

Figure 2: Multi-Dimensional Validation Framework for Synthetic Data

Validation Dimensions:

- Statistical Comparisons: Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests, correlation matrix analysis, and divergence measures (Jensen-Shannon, Kullback-Leibler) to ensure synthetic data replicates real data distributions [5]

- Model-Based Utility Testing: Training models on synthetic data and testing performance on real biological datasets to verify practical utility [5]

- Bias and Privacy Audits: Assessing re-identification risks and ensuring synthetic data doesn't perpetuate or amplify existing biases in biological datasets [5] [2]

- Expert Biological Review: Domain specialists evaluating whether synthetic data maintains biological plausibility and captures nuanced relationships [5]

Research Reagent Solutions for Synthetic Data Validation

The successful implementation of synthetic data in computational biology requires specialized tools and frameworks. The following table details essential research reagents for synthetic data generation and validation:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Synthetic Data in Computational Biology

| Reagent Category | Specific Tools/Techniques | Primary Function | Key Applications in Computational Biology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generative Models | GANs, VAEs, Diffusion Models, Transformers [6] [3] | Create synthetic datasets that preserve statistical properties of original biological data | Generating synthetic patient records, molecular structures, cellular imaging data |

| Validation Frameworks | Synthetic Data Metrics Library [1], Qualtrics Validation Trinity [5] | Systematically assess synthetic data quality across multiple dimensions | Benchmarking synthetic data fidelity, utility, and privacy preservation |

| Benchmarking Platforms | Open Problems in Single-Cell Analysis [4], AIMultiple Benchmark [9] | Provide standardized evaluation frameworks and comparative metrics | Cross-study comparison, method performance tracking, community standards |

| Privacy Protection Tools | Differential privacy, Bias audit frameworks [5] [2] | Ensure synthetic data doesn't reveal individual information or amplify biases | HIPAA/GDPR-compliant data sharing, fair model development |

| Synthetic Data Generators | YData, Mostly AI, Gretel, Synthetic Data Vault [1] [9] | Specialized platforms for high-fidelity synthetic data generation | Creating privacy-preserving versions of sensitive biological datasets |

Critical Analysis of Synthetic Data Limitations

Despite promising results, significant challenges persist in synthetic data implementation for computational biology:

Data Quality and Realism Concerns

Synthetic data may miss subtle biological patterns and complex interactions present in real-world systems. In the radiology reporting study, both GPT-4 and Yi-34B models made the most errors in inferring "composition" features when free text lacked standardized terminology, highlighting the challenge of capturing domain-specific nuance [7]. The "crisis of trust" remains a fundamental barrier to adoption, with concerns about AI "hallucinations" and loss of emotional nuance in synthetic outputs [6].

Bias Amplification and Representation Issues

Poorly designed generators can reproduce or exaggerate existing biases in training data. As noted in multiple sources, the same biases that exist in real data can carry over into synthetic data, potentially leading to underrepresentation of certain demographics or biological variations [1] [2] [10]. This is particularly problematic in healthcare applications where equitable performance across populations is critical.

Model Collapse and Performance Degradation

A phenomenon called "model collapse" occurs when AI models are repeatedly trained on synthetic data, leading to increasingly nonsensical outputs [2]. This raises concerns about the long-term viability of synthetic data approaches, especially as AI-generated content becomes more prevalent in biological datasets.

Validation Complexity and Benchmarking Fatigue

As the number of benchmarking studies surges—with 282 papers assessed in a single systematic review—the field risks "benchmarking fatigue" without clear standards for effective validation [4]. The absence of universally accepted terminology further complicates regulatory efforts and cross-study comparisons [3].

Future Directions and Recommendations

The evolving landscape of synthetic data in computational biology demands careful navigation of both promise and peril. Based on current evidence and emerging trends, the following recommendations emerge:

Adopt Hybrid Validation Approaches: Combine statistical metrics with biological expert review to ensure both technical quality and domain relevance [4] [5].

Implement Tiered-Risk Frameworks: Classify biological applications by risk level, reserving traditional validation for high-stakes decisions while using synthetic data for exploratory research [6].

Establish Governance and Ethics Councils: Proactively create cross-functional bodies to set standards for transparency, bias mitigation, and responsible use of synthetic data in biological research [6] [5].

Embrace Community-Led Standards: Participate in initiatives like "Open Problems in Single-Cell Analysis" to establish best practices and prevent benchmarking fragmentation [4].

Maintain Human-in-the-Loop Processes: Integrate domain expertise throughout the synthetic data lifecycle, from generation to validation, to catch nuances automated metrics might miss [5] [10].

The successful integration of synthetic data represents both a technological and cultural challenge for computational biology. Organizations that balance innovation with rigorous validation, transparency, and ethical oversight will be best positioned to harness the potential of synthetic data while mitigating its inherent risks.

The use of synthetic data is transforming computational biology, offering solutions to data scarcity, privacy concerns, and the need for robust benchmarking of AI models. However, its utility hinges entirely on rigorous validation that moves beyond mere statistical mimicry to demonstrate true domain relevance. Statistical similarity is a necessary but insufficient foundation; data must also maintain functional utility and biological plausibility to be trusted for critical research applications, particularly in drug development. This evaluation gap becomes particularly evident in specialized domains where general benchmarks fail to capture the nuanced requirements of biological research. Frameworks like the "validation trinity" of fidelity, utility, and privacy are essential, though these qualities often exist in tension, requiring careful balance based on the specific research context and risk tolerance [5].

The limitations of general academic benchmarks have been demonstrated in enterprise settings, where model rankings can significantly differ from their performance on specialized, domain-specific tasks [11]. This discrepancy underscores a critical lesson for computational biology: models excelling on general tasks may struggle with the complex, context-dependent challenges of biological data. Consequently, domain-specific benchmarking suites, analogous to the Domain Intelligence Benchmark Suite (DIBS) used in industry, are needed to accurately measure performance on specialized biological tasks such as protein structure prediction, pathway analysis, and molecular interaction modeling [11]. This article establishes a framework for such evaluation, combining rigorous validation methodologies with a concrete case study from virology to illustrate the critical need for domain-relevant assessment.

Foundational Methods for Synthetic Data Validation

Validating synthetic data requires a multi-faceted approach that progresses from basic statistical checks to advanced functional assessments. The following methodologies form the cornerstone of a comprehensive validation pipeline.

Statistical Validation Techniques

Statistical validation provides the first line of defense against poor-quality synthetic data by quantifying how well it preserves the properties of the original dataset.

Distribution Characteristic Comparison: This process begins with visual assessments like histogram overlays and quantile-quantile (QQ) plots, followed by formal statistical tests. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test measures the maximum deviation between cumulative distribution functions, while Jensen-Shannon divergence provides a symmetric metric for distributional similarity. For categorical variables common in biological classifications, Chi-squared tests evaluate whether frequency distributions match between real and synthetic datasets [12]. Implementation is straightforward with Python's SciPy library, using functions like

stats.ks_2samp(real_data_column, synthetic_data_column), where a p-value above 0.05 typically suggests acceptable similarity for most applications [12].Correlation Preservation Validation: Maintaining relationship patterns between variables is particularly crucial in biological datasets where variable interactions drive predictive power. This involves calculating correlation matrices using Pearson's coefficient for linear relationships, Spearman's rank for monotonic relationships, or Kendall's tau for ordinal data. The Frobenius norm of the difference between these matrices then quantifies overall correlation similarity with a single metric [12]. Heatmap comparisons can visually highlight specific variable pairs where synthetic data fails to maintain proper relationships, quickly identifying problematic areas requiring refinement in the generation process.

Outlier and Anomaly Analysis: Biological datasets often contain critical rare events, such as unusual protein folds or atypical cell responses, that must be preserved in synthetic versions. Techniques like Isolation Forest or Local Outlier Factor applied to both datasets allow comparison of the proportion and characteristics of identified outliers [12]. Significant differences in outlier proportions indicate potential issues with capturing the full data distribution, particularly at the extremes where scientifically significant findings often reside.

Machine Learning-Based Validation

While statistical validation ensures formal similarity, machine learning-based methods test the functional utility of synthetic data in practical applications.

Discriminative Testing with Classifiers: This approach trains binary classifiers (e.g., XGBoost or LightGBM) to distinguish between real and synthetic samples, creating a direct measure of how well the synthetic data matches the real data distribution [12]. A classification accuracy close to 50% (random chance) indicates high-quality synthetic data, while accuracy approaching 100% reveals easily detectable differences. Feature importance analysis from these classifiers can identify specific aspects where generation falls short, providing actionable insights for improvement.

Comparative Model Performance Analysis: Considered the ultimate test for AI evaluation purposes, this method trains identical machine learning models on both synthetic and real datasets, then evaluates them on a common test set of real data [12]. The closer the synthetic-trained model performs to the real-trained model across relevant metrics (accuracy, F1-score, RMSE, etc.), the higher the quality of the synthetic data. This approach has proven valuable in financial services for validating synthetic transaction data and is equally applicable to biological contexts like drug response prediction or protein function classification.

Transfer Learning Validation: Particularly valuable when real training data is scarce or highly sensitive, this method assesses whether knowledge gained from synthetic data transfers effectively to real-world problems. The methodology involves pre-training models on large synthetic datasets, then fine-tuning them on limited amounts of real data [12]. Significant performance improvements over baseline models trained only on limited real data indicate high-quality synthetic data that captures valuable, transferable patterns.

Table 1: Summary of Core Synthetic Data Validation Methods

| Validation Type | Key Methods | Primary Metrics | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Validation | Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, Jensen-Shannon divergence, Correlation matrix analysis | p-values, Divergence scores, Frobenius norm | Initial quality screening, Distribution preservation |

| Machine Learning Validation | Discriminative testing, Comparative performance, Transfer learning | Classification accuracy, Performance parity, Transfer efficacy | Functional utility assessment, Downstream task performance |

Domain-Specific Evaluation: A Case Study in Viral Structural Mimicry

The theoretical framework for synthetic data validation finds concrete application in computational biology through research into viral structural mimicry. This case study exemplifies the critical importance of domain-specific evaluation beyond statistical benchmarks.

Experimental Protocol for Mimicry Detection

Researchers at Arcadia Science developed a specialized pipeline for identifying viral structural mimics, which provides an excellent model for domain-relevant evaluation methodologies [13]. The experimental protocol can be summarized as follows:

Data Curation and Source Selection: The pipeline began with acquiring predicted protein structures from specialized databases: Viro3D for viral protein structures and AlphaFoldDB for human structures [13]. For viral structures, the team selected the higher quality score (pLDDT) between ColabFold and ESMFold predictions, with most being ColabFold structures. This careful sourcing from domain-specific repositories ensured biologically relevant input data rather than generic protein structures.

Structural Comparison and Analysis: Structural comparisons between viral and human proteins used Foldseek 3Di+AA to detect structural similarities even in the absence of sequence homology [13]. This approach was specifically chosen because shared structure often points to related function, which is the biological phenomenon of interest rather than mere structural similarity.

Statistical Evaluation and Threshold Determination: A key challenge was distinguishing "true" structural mimicry from broadly shared structural domains. The pipeline employed Bayesian Gaussian mixture modeling (GMM) to cluster top candidate matches between human structures and groups of related viral protein structures [13]. Instead of implementing a hard threshold, the researchers recommended that users set thresholds based on what type of relationships they're trying to discover and their tolerance for false positives or false negatives, acknowledging the domain-specific nature of these decisions.

The workflow below illustrates this comprehensive experimental protocol for detecting viral structural mimics.

Benchmarking and Evaluation Framework

The viral mimicry detection pipeline was rigorously evaluated using a carefully curated benchmark dataset comprising three categories of viral proteins [13]:

- Well-characterized mimics: Viral proteins with known specific human protein mimics and clear experimental evidence.

- Incompletely characterized mimics: Viral proteins described as mimics due to structural similarity but lacking experimental evidence for one specific human protein.

- Viral proteins with common domains: Proteins not expected to be mimics but having partial structural similarity due to shared functions (e.g., viral helicases and kinases).

This stratified benchmarking approach allowed the researchers to evaluate the pipeline's ability to distinguish true structural mimicry from broadly shared structural domains—a critical validation step for ensuring biological relevance rather than merely statistical similarity [13].

Table 2: Benchmark Dataset Composition for Viral Mimicry Detection

| Protein Category | Examples | Key Characteristics | Validation Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Well-characterized Mimics | BHRF1 (Bcl-2 mimic), VACWR034 (eIF2α mimic) | Clear experimental evidence, specific human protein target | Validate true positive detection rate |

| Incompletely Characterized Mimics | Proteins with shared structural features with many human proteins | Ambiguous classification, lack specific target | Test threshold sensitivity and specificity |

| Proteins with Common Domains | Viral helicases, kinases | Baseline structural similarity, ubiquitous counterparts | Evaluate false positive rate, establish baseline |

The Domain Intelligence Benchmarking Framework

The principles demonstrated in the viral mimicry case study can be formalized into a comprehensive Domain Intelligence Benchmarking Framework for computational biology. This framework adapts concepts from enterprise AI evaluation to biological contexts, addressing the unique challenges of biological data validation.

Core Components of the Framework

Established domain-specific benchmarking suites like the Domain Intelligence Benchmark Suite (DIBS) used in enterprise settings provide a valuable model for computational biology [11]. These suites typically focus on several core task categories highly relevant to biological research:

Structured Data Extraction: Converting unstructured biological text (research publications, clinical notes, lab reports) into structured formats like JSON for downstream analysis. In enterprise evaluations, even leading models achieved only approximately 60% accuracy on prompt-based Text-to-JSON tasks, suggesting this capability requires significant domain-specific refinement [11].

Tool Use and Function Calling: Enabling LLMs to interact with external biological databases, analytical tools, and APIs by generating properly formatted function calls. This capability is crucial for creating automated research workflows that integrate multiple data sources and analytical methods.

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG): Enhancing LLM responses by retrieving relevant information from specialized knowledge bases, such as protein databases, genomic repositories, or drug interaction databases. Enterprise evaluations revealed that academic RAG benchmarks often overestimate performance compared to specialized enterprise tasks, highlighting the need for domain-relevant testing [11].

The framework's implementation logic shows how these components integrate to form a comprehensive domain-specific evaluation system.

Comparative Performance in Specialized Domains

Evidence from enterprise evaluations demonstrates that model rankings can shift significantly between general benchmarks and domain-specific tasks. For instance, while GPT-4o performs well on academic benchmarks, Llama 3.1 405B and 70B perform similarly or better on specific function calling tasks in specialized domains [11]. This performance variability underscores why domain-specific benchmarking is essential for computational biology applications.

The capability to leverage retrieved context—crucial for RAG systems—also varies considerably between models. In enterprise testing, GPT-o1-mini and Claude-3.5 Sonnet demonstrated the greatest ability to effectively use retrieved context, while open-source Llama models and Gemini models trailed behind [11]. These performance gaps highlight specific areas for improvement in biological RAG systems, where accurately incorporating retrieved domain knowledge is essential for generating reliable insights.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Biology

Implementing robust synthetic data validation and domain-specific evaluation requires a toolkit of specialized solutions. The table below details key platforms and their relevant applications in computational biology research.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Domain-Specific Evaluation

| Tool/Platform | Key Features | Domain Applications | Open-Source Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Latitude | Human-in-the-loop evaluation, programmatic rules, LLM-as-Judge | Biological pathway validation, drug mechanism analysis, literature mining | Yes |

| Evidently AI | Live dashboards, synthetic data generation, over 100 quality metrics | Clinical trial data simulation, genomic data validation, experimental reproducibility | Yes (with cloud option) |

| NeuralTrust | RAG-focused evaluation, security and factual consistency | Molecular interaction verification, protein function annotation, drug-target validation | Yes (Community Edition) |

| Giskard | Vulnerability detection, AI Red Teaming, hallucination identification | Toxicity prediction validation, biomarker discovery, adverse event detection | Yes |

| Foldseek | Fast structural similarity search, 3Di+AA alignment | Protein function prediction, viral mimicry detection, structural biology | Yes |

The validation of synthetic data in computational biology must extend far beyond statistical mimicry to demonstrate true domain relevance. As illustrated by the viral structural mimicry case study, biological significance rather than mathematical similarity must be the ultimate benchmark for synthetic data quality. Frameworks like the Domain Intelligence Benchmarking Framework adapted from enterprise applications provide a structured approach for this domain-specific evaluation, while specialized research reagent solutions enable practical implementation.

Future progress in this field will require developing even more sophisticated biological task benchmarks, creating standardized validation protocols specific to major subdisciplines (e.g., genomics, proteomics, drug discovery), and establishing consensus metrics for functional utility in biological contexts. As synthetic data becomes increasingly integral to computational biology research, robust domain-relevant evaluation will be essential for ensuring these powerful tools generate biologically meaningful insights rather than statistically plausible artifacts.

In the field of computational biology, where research is often constrained by limited access to sensitive patient data, synthetic data has emerged as a transformative solution. It enables the creation of artificial datasets that mimic the statistical properties of real-world biological and healthcare data, thus accelerating research while addressing critical privacy concerns. However, the value of synthetic data hinges on its rigorous validation across three interdependent dimensions: fidelity, utility, and privacy—a framework often termed the "Validation Trinity" [14] [15].

Fidelity measures the statistical similarity between synthetic and real data, ensuring the artificial dataset accurately reflects the original data's distributions, correlations, and structures [14] [16]. Utility assesses the synthetic data's practical usefulness for specific analytical tasks, such as training machine learning models or deriving scientific insights [14] [17]. Privacy evaluates the risk that synthetic data could be used to re-identify individuals or infer sensitive information from the original dataset [14] [15]. This guide objectively compares synthetic data generation methodologies by examining experimental data across these three pillars, providing computational biologists with a framework for selecting appropriate techniques for their research benchmarks.

Experimental Framework and Comparative Methodology

Standardized Evaluation Protocols

To ensure consistent comparison across synthetic data generation techniques, researchers employ standardized evaluation protocols. The core experimental workflow typically involves splitting a real dataset into training and hold-out test sets, generating synthetic data from the training set, and then evaluating the synthetic data against the hold-out set across fidelity, utility, and privacy dimensions [15] [17]. This process is repeated multiple times for each generative model to account for stochastic variations, with results aggregated to provide robust performance metrics [17].

Evaluations utilize multiple real-world datasets representing different domains and characteristics. For computational biology applications, health datasets of varying sizes (from under 100 to over 40,000 patients) and complexity levels are particularly relevant, ensuring findings generalize across different research contexts [17]. The following diagram illustrates the standard experimental workflow for synthetic data validation:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Metrics and Measures

Researchers evaluating synthetic data require specific metrics and tools to quantitatively assess each dimension of the Validation Trinity. The table below catalogs essential validation reagents, their measurement functions, and ideal value ranges:

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Synthetic Data Validation

| Metric/Measure | Validation Dimension | Measurement Function | Ideal Value Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hellinger Distance | Fidelity | Quantifies similarity between probability distributions of real and synthetic data [16] | Closer to 0 indicates higher similarity |

| Pairwise Correlation Difference (PCD) | Fidelity | Measures preservation of correlation structures between variables [16] | Closer to 0 indicates better correlation preservation |

| Train Synthetic Test Real (TSTR) | Utility | Evaluates performance of models trained on synthetic data when tested on real data [18] [15] | Comparable to Train Real Test Real (TRTR) performance |

| Feature Importance Score | Utility | Compares feature importance rankings between models trained on synthetic vs. real data [15] | High correlation between rankings |

| Membership Inference Score | Privacy | Measures risk of determining whether specific records were in training data [18] [15] | Lower values indicate better privacy protection |

| Attribute Inference Risk | Privacy | Assesses risk of inferring sensitive attributes from synthetic data [18] | Lower values indicate better privacy protection |

| Exact Match Score | Privacy | Counts how many real records are exactly reproduced in synthetic data [15] | 0 (no exact matches) |

| Dichlorobenzenetriol | Dichlorobenzenetriol, CAS:94650-90-5, MF:C6H4Cl2O3, MW:195.00 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Guanidine, monobenzoate | Guanidine, monobenzoate, CAS:26739-54-8, MF:C8H11N3O2, MW:181.19 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Comparative Analysis of Synthetic Data Generation Methods

Performance Across the Validation Trinity

Different synthetic data generation approaches demonstrate distinct performance characteristics across the three validation dimensions. The following table summarizes experimental findings from comparative studies evaluating various generation techniques on healthcare datasets:

Table: Comparative Performance of Synthetic Data Generation Methods

| Generation Method | Fidelity Performance | Utility Performance | Privacy Performance | Best Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-DP Synthetic Models | Good statistical fidelity compared to real data [19] | Maintains utility without evident privacy breaches [19] | No strong evidence of privacy breaches [19] | Internal research with lower privacy risks |

| DP-Enforced Models | Significantly disrupted correlation structures [19] [20] | Reduced utility due to added noise [16] | Enhanced privacy preservation [16] | Data sharing with strict privacy requirements |

| K-Anonymization | Produces high fidelity data [19] | Maintains utility for some analyses | Notable privacy risks [19] | Legacy systems requiring simple anonymization |

| Fidelity-Agnostic Synthetic Data (FASD) | Lower fidelity by design [18] | Improves performance in prediction tasks [18] | Better privacy due to reduced resemblance [18] | Task-specific applications where prediction is primary goal |

| MIIC-SDG Algorithm | Accurately captures underlying multivariate distribution [21] | High quality for complex analyses | Effective privacy preservation [21] | Clinical trials with limited patients where relationships must be preserved |

The Fundamental Trade-Off Relationships

Experimental evidence consistently demonstrates a fundamental trade-off between the three validation dimensions. Studies evaluating synthetic data generated with differential privacy (DP) guarantees found that while DP enhanced privacy preservation, it often significantly reduced both fidelity and utility by disrupting correlation structures in the data [19] [16] [20]. Conversely, non-DP synthetic models demonstrated good fidelity and utility without evident privacy breaches in controlled settings [19].

Research on fidelity-agnostic approaches reveals that synthetic data need not closely resemble real data to be useful for specific prediction tasks, and this reduced resemblance can actually improve privacy protection [18]. This challenges the traditional paradigm that prioritizes maximum fidelity, suggesting that task-specific optimization may yield better outcomes across the utility-privacy spectrum.

The relationship between these dimensions can be visualized as a triangular trade-off space where optimization toward one vertex often necessitates compromises elsewhere:

Implementation Protocols for Computational Biology

Validating Synthetic Data for Specific Research Applications

For computational biologists implementing synthetic data in their research pipelines, validation protocols should be tailored to specific use cases. The following experimental protocols are recommended based on published methodologies:

Protocol 1: Machine Learning Applications

- Split original biological dataset into training (70%) and test sets (30%)

- Generate synthetic data from training set using selected generative model

- Train machine learning models on both synthetic data and real training data

- Compare performance using TSTR (Train Synthetic Test Real) and TRTR (Train Real Test Real) frameworks on the same test set [18] [15]

- Evaluate feature importance similarity between models trained on synthetic versus real data [15]

- Assess privacy risks using membership inference attacks on the synthetic data [18]

Protocol 2: Statistical Analysis and Data Sharing

- Generate synthetic dataset from complete original dataset

- Evaluate fidelity using Hellinger distance for marginal distributions and Pairwise Correlation Difference (PCD) for relationship preservation [16]

- Conduct statistical analyses (e.g., hypothesis tests, regression models) on both synthetic and real data

- Compare results and effect sizes between analyses

- Assess re-identification risks using metrics like k-map and δ-presence [18]

- For data sharing, implement differential privacy with privacy budget (ε) tailored to sensitivity requirements [16]

Decision Framework for Method Selection

Choosing the appropriate synthetic data generation method requires careful consideration of research goals, privacy requirements, and analytical needs. The following decision framework is recommended:

- For exploratory analysis and method development where privacy concerns are moderate: Non-DP synthetic models generally provide the best balance of fidelity and utility [19]

- For sharing data with external collaborators or public release: DP-enforced models provide mathematical privacy guarantees despite some fidelity loss [16]

- For specific predictive modeling tasks where relationships matter more than exact distributions: Fidelity-agnostic approaches (FASD) may provide superior utility and privacy [18]

- For complex clinical datasets with intricate multivariate relationships: Structure-learning methods like MIIC-SDG that explicitly model relationships may outperform general-purpose approaches [21]

The Validation Trinity of fidelity, utility, and privacy provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating synthetic data in computational biology research. Experimental evidence demonstrates that no single approach dominates across all three dimensions, necessitating thoughtful selection based on research context and requirements. Non-DP methods currently offer the best fidelity and utility for internal research, while DP-enforced models provide stronger privacy guarantees for data sharing, albeit with performance costs. Emerging approaches like fidelity-agnostic generation and structure-learning algorithms suggest promising directions for overcoming these traditional trade-offs.

As synthetic data technologies evolve, standardization of validation metrics and protocols will be crucial for meaningful comparison across studies. Computational biologists should implement tiered validation strategies that assess all three dimensions of the Validation Trinity, with emphasis on metrics most relevant to their specific research questions. By adopting this comprehensive approach to validation, researchers can harness the power of synthetic data to accelerate biological discovery while maintaining rigorous standards for privacy protection.

Synthetic data generation has emerged as a pivotal technology for advancing artificial intelligence in medicine and computational biology, addressing critical challenges of data scarcity, privacy concerns, and the need for robust validation benchmarks. The growing adoption of synthetic medical data (SMD) enables researchers to supplement limited patient datasets, particularly for rare diseases and underrepresented populations, while facilitating the sharing of data without compromising patient privacy [22]. However, the utility of synthetic data hinges entirely on its quality and biological plausibility. As the field confronts the fundamental principle of "garbage in, garbage out," establishing comprehensive evaluation frameworks has become essential for ensuring synthetic data reliably supports drug development and biological discovery [22].

The 7 Cs Framework represents a paradigm shift in synthetic data validation, moving beyond traditional statistical metrics to address the unique requirements of medical and biological applications. Developed specifically for healthcare contexts, this framework provides a structured approach to evaluate synthetic datasets across multiple clinically relevant dimensions [22] [23]. For computational biologists and pharmaceutical researchers, this comprehensive validation approach offers the methodological rigor needed to establish trustworthy benchmarks for evaluating algorithms, simulating clinical trials, and modeling biological systems.

Framework Fundamentals: The 7 Cs Explained

The 7 Cs Framework introduces seven complementary criteria for holistic synthetic data assessment, addressing both statistical fidelity and clinical/biological relevance. Unlike earlier approaches that primarily focused on statistical similarity, this multidimensional assessment captures the complex requirements of biomedical data [22]. The framework emphasizes that over-optimizing for a single metric (a phenomenon described by Goodhart's Law) can compromise other essential data qualities, necessitating balanced evaluation across all dimensions [22].

The table below outlines the seven core criteria with their definitions and significance in biological research contexts:

| Criterion | Definition | Research Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Congruence | Statistical alignment between distributions of synthetic and real data [22] | Ensures synthetic data maintains statistical properties of original biological datasets |

| Coverage | Extent to which synthetic data captures variability, range, and novelty in real data [22] | Evaluates whether data represents full spectrum of biological heterogeneity and rare subpopulations |

| Constraint | Adherence to anatomical, biological, temporal, or clinical constraints [22] | Critical for maintaining biological plausibility and respecting known physiological boundaries |

| Completeness | Inclusion of all necessary details and metadata relevant to the research task [22] | Ensures synthetic datasets contain essential annotations, features, and contextual information |

| Compliance | Adherence to data format standards, privacy requirements, and regulatory guidelines [22] | Facilitates data interoperability and ensures ethical use in regulated research environments |

| Comprehension | Clarity and interpretability of the synthetic dataset and its limitations [22] | Enables researchers to appropriately understand and apply synthetic data in biological models |

| Consistency | Coherence and absence of contradictions within the synthetic dataset [22] | Ensures logical relationships between biological variables are maintained throughout the dataset |

Table 1: The 7 Cs of Synthetic Medical Data Evaluation

Comparative Analysis: The 7 Cs Versus Alternative Frameworks

Specialized Frameworks for Medical and Biological Data

When selecting a validation framework for synthetic biological data, researchers must choose between approaches with different philosophical foundations and technical requirements. The following comparison examines the 7 Cs Framework against other established methodologies:

| Framework | Primary Focus | Key Strengths | Limitations | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 Cs Framework | Comprehensive medical data evaluation [22] | Domain-specific clinical relevance; addresses constraints and compliance | Complex implementation; requires medical expertise | Clinical trial simulations; medical AI development; regulatory submissions |

| METRIC-Framework | Medical training data for AI systems [24] | 15 specialized dimensions; systematic bias assessment | Focused specifically on ML training data | Training dataset curation; bias mitigation in medical AI |

| Traditional Statistical Methods | Distribution alignment and fidelity [22] [25] | Established metrics; computational efficiency | Fails to detect clinical implausibility; limited scope | Initial data generation tuning; technical validation |

| Quasi-Experimental Methods | Causal inference in policy evaluation [26] | Robust causal estimation; handles observational data | Not designed for synthetic data validation | Policy impact studies; observational research |

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Synthetic Data Evaluation Frameworks

The 7 Cs Framework distinguishes itself through its specific design for medical applications and comprehensive attention to clinical validity. Where traditional statistical methods like Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) or Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests primarily evaluate distributional alignment, the 7 Cs Framework additionally assesses whether data respects biological constraints and contains necessary contextual information [22]. This is particularly critical in drug development, where synthetic data must faithfully represent pathophysiological mechanisms and clinical outcomes.

Quantitative Assessment Metrics

For each criterion, the 7 Cs Framework provides specific quantitative metrics that enable reproducible assessment of synthetic data quality:

| Criterion | Assessment Metrics | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Congruence | Cosine Similarity, FID, BLEU score [22] | Metric selection depends on data modality (images, text, tabular) |

| Coverage | Convex Hull Volume, Clustering-Based metrics, Recall, Variance, Entropy [22] | Evaluates both representation of majority patterns and rare cases |

| Constraint | Constraint Violation Rate, Nearest Invalid Datapoint, Distance to Constraint Boundary [22] | Requires explicit definition of biological/clinical constraints |

| Completeness | Proportion of Required Fields, Missing Data Percentage, scaling-based metrics [22] | Dependent on well-specified requirements for the research task |

| Compliance | Format adherence metrics, privacy preservation measures [22] | Must address regulatory standards (e.g., FDA, EMA requirements) |

| Comprehension | Interpretability scores, documentation completeness [22] | Qualitative and quantitative assessment of clarity |

| Consistency | Logical contradiction checks, relationship validation [22] | Evaluates internal coherence across the dataset |

Table 3: Quantitative Metrics for the 7 Cs Framework

Experimental Implementation and Workflows

Implementation Methodology

Implementing the 7 Cs Framework requires a systematic approach that spans the entire synthetic data lifecycle. The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages in applying the framework to validate synthetic biological data:

Diagram 1: 7 Cs Framework Implementation Workflow

Experimental Protocols for Framework Application

Protocol 1: Constraint Validation for Biological Data

Purpose: To verify that synthetic data respects known biological constraints and anatomical relationships.

Methodology:

- Define Explicit Constraints: Enumerate biological, anatomical, and clinical constraints relevant to the dataset (e.g., valid lab value ranges, anatomical relationships, physiological limitations) [22].

- Establish Validation Rules: Convert constraints into computable validation rules (e.g., "serum creatinine ≤ 5 mg/dL," "heart must have four chambers," "tumor size ≥ 0 mm").

- Quantify Violation Rate: Calculate the Constraint Violation Rate as the proportion of synthetic data points violating established constraints [22].

- Measure Boundary Adherence: Compute Distance to Constraint Boundary to assess how close synthetic data points approach invalid regions [22].

- Benchmark Against Real Data: Compare constraint adherence between synthetic and real datasets to identify systematic deviations.

Interpretation: High constraint violation rates indicate fundamental flaws in data generation, potentially compromising utility for biological discovery.

Protocol 2: Coverage Assessment for Rare Subpopulations

Purpose: To evaluate how well synthetic data represents the full heterogeneity of biological systems, including rare cell types, genetic variants, or clinical presentations.

Methodology:

- Feature Space Mapping: Project both real and synthetic data into a lower-dimensional feature space using PCA or UMAP.

- Convex Hull Analysis: Calculate the volume of convex hulls containing real and synthetic data points to assess coverage breadth [22].

- Cluster-Based Evaluation: Apply clustering algorithms to identify distinct subpopulations in real data and measure their representation in synthetic data.

- Novelty Detection: Identify synthetic data points falling outside regions occupied by real data and assess their biological plausibility.

- Diversity Metrics: Compute entropy and variance measures to quantify diversity within and between biological subgroups.

Interpretation: Effective synthetic data should match the coverage of real data while introducing novel but plausible variations that enhance diversity without violating biological constraints.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Solutions for Synthetic Data Validation

Implementing comprehensive synthetic data validation requires specialized methodological approaches and computational tools. The following table details essential solutions for researchers applying the 7 Cs Framework:

| Solution Category | Specific Tools/Methods | Function in Validation Process |

|---|---|---|

| Distribution Alignment | Fréchet Inception Distance (FID), Cosine Similarity, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test [22] [25] | Quantifies congruence between synthetic and real data distributions |

| Coverage Assessment | Convex Hull Volume, clustering algorithms, entropy measures [22] | Evaluates representation of data variability and rare subpopulations |

| Constraint Formulation | Domain knowledge graphs, clinical guidelines, biological pathway databases [22] | Encodes biological and clinical constraints for automated validation |

| Generative Models | GANs, Denoising Diffusion Models, Adversarial Random Forests, R-vine copulas [22] [25] | Creates synthetic data with different trade-offs across the 7 Cs |

| Tabular Data Generation | Adversarial Random Forest (ARF), R-vine copula models [25] | Specialized approaches for complex tabular data with mixed variable types |

| Privacy Assurance | Differential privacy, k-anonymity, synthetic data quality metrics [22] | Ensures compliance with privacy regulations and ethical guidelines |

| Antiamoebin | Antiamoebin, CAS:12692-85-2, MF:C80H123N17O20, MW:1642.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1,3,5-Trioxanetrione | 1,3,5-Trioxanetrione (C3O6) | 1,3,5-Trioxanetrione is an unstable, cyclic trimer of carbon dioxide for research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Table 4: Essential Research Solutions for Synthetic Data Validation

Application in Computational Biology and Drug Development

The 7 Cs Framework provides particular value for specific applications in computational biology and pharmaceutical research:

Clinical Trial Simulation and Optimization

Synthetic data enables in silico trials that can optimize study design and predict outcomes before expensive real-world trials [25]. For these applications, Coverage ensures adequate representation of patient diversity, while Constraint maintains physiological plausibility in simulated treatment responses. Sequential generation approaches that mimic trial chronology (baseline → randomization → follow-up) have demonstrated particular effectiveness for tabular clinical trial data [25].

Rare Disease Modeling

For rare conditions where real patient data is scarce, synthetic data generation must balance Congruence with the limited available data against Coverage of the condition's full clinical spectrum. The 7 Cs Framework guides this balancing act by emphasizing the need for clinically valid variations that expand beyond the specific patterns in small original datasets.

Multi-Omics Data Integration

In complex biological domains involving genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics, Consistency across data modalities becomes critical. The framework ensures that synthetic multi-omics data maintains biologically plausible relationships between different molecular layers, preventing generation of genetically impossible profiles.

The 7 Cs Framework represents a significant advancement in synthetic data validation for medical and biological applications. By moving beyond purely statistical measures to incorporate clinical relevance, biological constraints, and practical utility, it addresses the unique challenges faced by computational biologists and pharmaceutical researchers. As synthetic data becomes increasingly central to drug development and biological discovery, this comprehensive framework provides the methodological rigor needed to establish trustworthy benchmarks, validate computational models, and accelerate innovation while maintaining scientific validity.

The framework's structured approach enables researchers to identify specific strengths and limitations of synthetic datasets, guiding appropriate application across different use cases from clinical trial simulation to rare disease modeling. By emphasizing the importance of constraint adherence, coverage diversity, and biological plausibility, the 7 Cs Framework supports the generation of synthetic data that truly advances biological understanding and therapeutic development.

Current Gaps and the Push for Standardized Metrics in Life Sciences

The adoption of synthetic data for computational biology benchmarks represents a paradigm shift in life sciences research, offering solutions for data privacy, scarcity, and method validation. However, significant gaps persist in standardization and validation frameworks. This guide examines the current landscape through the lens of a benchmark study on differential abundance methods, comparing experimental and synthetic data approaches to identify critical metrics and methodological considerations for researchers and drug development professionals.

Synthetic data generation has emerged as a critical tool for addressing complex challenges in life sciences research, particularly in computational biology where data privacy, scarcity, and reproducibility are significant concerns. In 2025, synthetic data is transitioning from experimental to operational necessity, with Gartner forecasting that by 2030, synthetic data will be more widely used for AI training than real-world datasets [10]. The life sciences sector, characterized by massive data requirements and stringent privacy regulations, stands to benefit substantially from properly validated synthetic data approaches.

This comparison guide focuses specifically on validating synthetic data for benchmarking differential abundance (DA) methods in microbiome studies—a domain where statistical interpretation is notably challenged by data sparsity and compositional nature [27]. Through examination of a specific benchmark case study, we evaluate the efficacy of synthetic data in replicating experimental findings, identify persistent gaps in validation frameworks, and propose standardized metrics for future research.

Experimental Protocols: Validating Synthetic Data for Microbiome Benchmarking

Study Design and Workflow

The foundational study for this comparison aimed to validate whether synthetic data could replicate findings from a reference benchmark study by Nearing et al. that assessed 14 differential abundance tests using 38 experimental 16S rRNA datasets in a case-control design [27]. The validation study adhered to a pre-specified computational protocol following SPIRIT guidelines to ensure transparency and minimize bias.

The core methodology involved:

- Data Simulation: Generating synthetic datasets using two distinct tools (metaSPARSim and sparseDOSSA2) calibrated against the 38 experimental datasets

- Multiple Realizations: Creating 10 synthetic data realizations for each experimental template to assess simulation noise impact

- Equivalence Testing: Conducting statistical equivalence tests on 30 data characteristics comparing synthetic and experimental data

- Method Application: Applying the same 14 DA tests to both synthetic and experimental datasets

- Consistency Evaluation: Measuring consistency in significant feature identification and proportion of significant features per tool [27]

Simulation Tools and Technical Implementation

The study employed two published simulation tools specifically designed for 16S rRNA sequencing data, with implementations as follows:

metaSPARSim Implementation:

sparseDOSSA2 Implementation:

Both tools offer calibration functionality to ensure synthetic data reflects the experimental template characteristics, with specific attention to maintaining zero-inflation patterns (sparsity) and correlation structures inherent in microbiome data [27].

Comparative Analysis: Experimental vs. Synthetic Data Performance

Quantitative Results from Microbiome Benchmark Validation

Table 1: Hypothesis Validation Rates Using Synthetic Data

| Validation Category | Number of Hypotheses | Full Validation Rate | Partial Validation Rate | Non-Validation Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Results | 27 | 6 (22%) | 10 (37%) | 11 (41%) |

| metaSPARSim Performance | N/A | Similar to reference | Moderate consistency | Varied by dataset |

| sparseDOSSA2 Performance | N/A | Similar to reference | Moderate consistency | Varied by dataset |

The validation study revealed that of 27 hypotheses tested from the original benchmark, only 6 (22%) were fully validated when using synthetic data, while 10 (37%) showed similar trends, and 11 (41%) could not be validated [27]. This demonstrates both the potential and limitations of current synthetic data approaches for computational benchmark validation.

Data Characteristic Equivalence Results

Table 2: Synthetic vs. Experimental Data Characteristic Comparison

| Data Characteristic Category | Equivalence Rate | Key Discrepancies | Impact on DA Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Compositional Metrics | High (>80%) | Minimal | Low |

| Sparsity Patterns | Moderate (60-80%) | Structural zeros | Moderate |

| Inter-feature Correlations | Moderate (60-80%) | Complex dependencies | Moderate to High |

| Abundance Distributions | High (>80%) | Tail behavior | Low to Moderate |

| Effect Size Preservation | Variable (40-70%) | Magnitude in low abundance | High |

The equivalence testing on 30 data characteristics revealed that while basic compositional metrics were well-preserved in synthetic data, more complex characteristics like sparsity patterns and inter-feature correlations showed moderate equivalence, with direct impact on differential abundance test results [27].

Critical Gaps in Current Synthetic Data Validation

Standardization and Metric Deficiencies

The validation study uncovered several critical gaps in the current approach to synthetic data validation for computational benchmarks:

Standardized Metric Framework: No consistent framework exists for evaluating synthetic data quality across studies. The research team had to develop custom equivalence tests for 30 data characteristics, with varying success in establishing meaningful thresholds for acceptance [27].

Reproducibility Challenges: Differences in software versions between the original study and validation effort introduced confounding variables. The study used the most recent versions of DA methods, which potentially altered performance characteristics independent of data quality issues [27].

Qualitative Translation Gaps: Hypothesis testing proved particularly challenging when translating qualitative observations from the original study text into testable quantitative hypotheses, resulting in approximately 41% of hypotheses being non-validatable even with reasonable synthetic data [27].

Life Sciences Industry Context

Beyond methodological gaps, the life sciences industry faces broader challenges in synthetic data adoption. The Deloitte 2025 Life Sciences Outlook identifies that while 60% of executives cite digital transformation and AI as key trends, and nearly 60% plan to increase generative AI investments, standardized metrics for evaluating these technologies remain lacking [28]. Specifically, organizations struggle with developing "consistent metrics, as digital projects span diverse goals including risk management, operational efficiency, and customer satisfaction that don't easily compare under one measure like ROI" [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Synthetic Data Validation

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Validation | Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation Platforms | metaSPARSim, sparseDOSSA2, MB-GAN, nuMetaSim | Generate synthetic datasets from experimental templates | Tool selection should match data modality and study objectives |

| Differential Abundance Methods | 14 tests from Nearing et al. study (e.g., DESeq2, edgeR, metagenomeSeq) | Benchmark performance comparison between data types | Version control critical; performance characteristics change between updates |

| Statistical Equivalence Testing | TOST procedure, PCA similarity metrics, effect size comparisons | Quantify similarity between synthetic and experimental data | Requires pre-defined equivalence thresholds specific to application domain |

| Data Characterization Metrics | Sparsity indices, compositionality measures, correlation structures | Profile dataset characteristics for comparison | Must capture biologically relevant features specific to microbiome data |

| Protocol Reporting Frameworks | SPIRIT guidelines, computational study protocols | Ensure transparency and reproducibility | Requires significant effort for planning, execution, and documentation |

| Trioctacosyl phosphate | Trioctacosyl Phosphate | Trioctacosyl Phosphate is For Research Use Only (RUO). It is a long-chain organophosphate ester. Not for human, veterinary, or household use. | Bench Chemicals |

| 1,4-Dioxane-2,3-diol, cis- | 1,4-Dioxane-2,3-diol, cis-, CAS:67907-43-1, MF:C4H8O4, MW:120.10 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Pathway to Standardization: Recommended Metrics and Framework

Proposed Standardized Metric Framework

Based on the experimental findings, we propose a hierarchical validation framework for synthetic data in computational biology benchmarks:

Implementation Considerations for Life Sciences Organizations

Successfully implementing synthetic data validation requires addressing both technical and organizational challenges:

Technical Implementation:

- Establish pre-specified computational protocols following SPIRIT or similar guidelines before initiating benchmark studies

- Implement version-controlled pipelines for simulation tools and analytical methods

- Define equivalence thresholds specific to biological contexts and application domains

Organizational Considerations:

- Develop prioritization frameworks for digital investments similar to R&D pipeline management [28]

- Balance the complexity and runtime of validation studies with the requirements for realistic simulation

- Invest in data science capabilities and analytics infrastructure for multimodal data strategy [28]

The validation of synthetic data for computational biology benchmarks remains challenging but essential for advancing life sciences research. This comparison demonstrates that while synthetic data can replicate many characteristics of experimental data and validate a portion of benchmark findings, significant gaps persist in standardization and comprehensive validation.

The life sciences sector's increasing reliance on digital transformation and AI-driven approaches [28] makes addressing these gaps imperative. By adopting standardized metrics, transparent protocols, and hierarchical validation frameworks, researchers can enhance the reliability of synthetic data for benchmarking computational methods, ultimately accelerating drug development and biological discovery.

Future efforts should focus on developing domain-specific equivalence thresholds, improving simulation of complex data characteristics like structural zeros, and establishing reporting standards that enable cross-study comparison and meta-analysis of benchmark validations.

How to Validate: Statistical, ML, and Domain-Specific Methods for Biological Data

In computational biology, the adoption of synthetic data is accelerating, offering solutions to data scarcity, privacy constraints, and the need for controlled benchmark environments. The utility of this synthetic data, however, is entirely contingent on its statistical fidelity to real-world experimental data. For research involving complex biological systems—from microbiome analyses to disease progression models—ensuring that synthetic datasets accurately replicate the distributions, correlations, and outlier patterns of the original data is paramount. This guide provides a structured, methodological approach for researchers and drug development professionals to validate synthetic data, ensuring it is fit for purpose in computational benchmarks and high-stakes biological research.

Statistical Foundations of Synthetic Data Validation

Statistical validation forms the foundational layer of any synthetic data assessment, providing quantifiable measures of how well the artificial data preserves the properties of the original dataset [12]. A robust validation strategy typically progresses from univariate distribution analysis to multivariate relationship mapping and finally to anomaly detection.

Core Principles: The overarching goal is to demonstrate that the synthetic data is not merely statistically similar but is functionally equivalent for downstream analytical tasks. Key metrics for evaluation include accuracy (how closely synthetic data matches real data characteristics), diversity (coverage of scenarios and edge cases), and realism (how convincingly it mimics real-world information) [10]. Proper validation requires ahold-out set of real-world data that the synthetic data has never seen, serving as the benchmark for all comparisons [10] [12].

Comparative Frameworks and Quantitative Metrics

A multi-faceted validation approach is crucial. The table below summarizes the core statistical methods and their application to synthetic data assessment in biological contexts.

Table 1: Statistical Methods for Synthetic Data Validation

| Validation Dimension | Core Methodology | Key Metrics & Statistical Tests | Application in Computational Biology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distribution Comparison | Visual inspection and statistical testing of univariate and multivariate distributions [12]. | Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, Jensen-Shannon divergence, Wasserstein distance, Chi-squared test for categorical data [12]. | Validating the distribution of microbial abundances, gene expression levels, or patient biomarkers in synthetic cohorts [29] [30]. |

| Correlation Preservation | Comparison of relationship patterns between variables in real and synthetic datasets [12]. | Pearson's correlation (linear), Spearman's rank (monotonic), Frobenius norm of correlation matrix differences [12]. | Ensuring synthetic genomic or proteomic data maintains gene co-expression patterns or protein-protein interaction networks [12]. |

| Outlier & Anomaly Analysis | Identifying and comparing edge cases and anomalous patterns between datasets [12]. | Isolation Forest, Local Outlier Factor, comparison of anomaly score distributions and proportions [12]. | Confirming that rare but clinically significant anomalies (e.g., rare microbial species, extreme drug responses) are represented [12]. |

| Discriminative Testing | Training a classifier to distinguish real from synthetic samples [12]. | Classification accuracy (ideally near 50%, indicating indistinguishability) [12]. | A functional test of overall realism for complex, high-dimensional biological data. |

Quantitative benchmarks provide critical performance thresholds. For instance, in distribution similarity tests like Kolmogorov-Smirnov, p-values > 0.05 often suggest acceptable similarity, though more stringent applications may require p > 0.2 [12]. In independent benchmarks, such as the 2025 AIMultiple evaluation, top-performing synthetic data generators demonstrated superior capability in minimizing correlation distance (Δ), Kolmogorov-Smirnov distance (K), and Total Variation Distance (TVD) for categorical features [9].

Experimental Protocols for Rigorous Validation

Protocol for Distribution Comparison

Objective: To validate that the synthetic data replicates the marginal and joint distributions of the original experimental data.

Detailed Methodology:

- Visual Assessment: Begin with intuitive visual checks. For each numerical variable, generate overlaid histograms and kernel density plots of the real and synthetic data. Create Q-Q (quantile-quantile) plots to inspect distributional alignment across the entire value range [12].

- Statistical Testing: Apply formal statistical tests to quantify similarity.

- For continuous variables, use the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test to measure the maximum deviation between cumulative distribution functions. Implementation can be done via Python's SciPy library:

stats.ks_2samp(real_data_column, synthetic_data_column)[12]. - For categorical variables, employ a Chi-squared test to evaluate if frequency distributions match [12].

- For continuous variables, use the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test to measure the maximum deviation between cumulative distribution functions. Implementation can be done via Python's SciPy library:

- Multivariate Extension: For biological systems where variable interactions are critical, analyze joint distributions using techniques like Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD) or copula comparisons to ensure complex dependencies are captured [12].

Protocol for Correlation Preservation Validation

Objective: To verify that inter-variable relationships and dependency structures are maintained in the synthetic data.

Detailed Methodology:

- Correlation Matrix Calculation: Compute correlation matrices for both the real and synthetic datasets. Use:

- Pearson's coefficient for linear relationships.

- Spearman's rank for monotonic relationships.

- Kendall's tau for ordinal data [12].

- Similarity Quantification: Calculate the Frobenius norm of the difference between the two correlation matrices. This provides a single metric quantifying overall correlation similarity [12].

- Visual Diagnostics: Create heatmap comparisons that highlight variable pairs where the synthetic data shows the largest correlation discrepancies. This pinpoints specific areas for refinement in the generation process [12].

Protocol for Outlier and Anomaly Analysis

Objective: To ensure that the synthetic data accurately represents rare but critical edge cases.

Detailed Methodology:

- Anomaly Detection: Apply an anomaly detection algorithm, such as Isolation Forest, to both the real and synthetic datasets.

- Implementation example:

IsolationForest(contamination=0.05).fit_predict(data)identifies the most anomalous 5% of records [12].

- Implementation example:

- Proportion and Pattern Comparison: Compare the proportion and characteristics of identified outliers between datasets. The distribution of anomaly scores should show similar patterns [12].

- Targeted Validation: In domains like healthcare, tag known rare but significant anomalies in the original dataset before synthesis. Then, measure the synthetic data's ability to recreate similar outlier patterns, thus preventing dangerous blind spots in diagnostic AI systems [12].

The following workflow diagram synthesizes these protocols into a cohesive validation pipeline.

Synthetic Data Validation Workflow for Robust Benchmarks

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Computational Solutions

Beyond statistical theory, practical validation requires a suite of computational tools and frameworks. The following table details essential "research reagents" for conducting rigorous synthetic data validation.

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Synthetic Data Validation

| Tool / Solution | Type | Primary Function in Validation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| SciPy (Python) [12] | Statistical Library | Provides functions for key statistical tests (e.g., ks_2samp for KS test). |

Quantifying the similarity between distributions of a real and synthetic biological variable. |

| scikit-learn (Python) [12] | Machine Learning Library | Offers implementations for discriminative testing and anomaly detection (e.g., IsolationForest). |

Training a classifier to distinguish real from synthetic data, or identifying outliers in both datasets. |

| Discriminative Classifier (e.g., XGBoost) [12] | ML Model | A direct functional test of synthetic data realism. | Assessing if a model can differentiate synthetic from real microbiome samples based on their feature vectors. |

| Automated Validation Pipeline (e.g., Apache Airflow) [12] | Orchestration Framework | Automates a sequence of validation steps for consistency and reproducibility. | Creating a continuous integration pipeline that validates new synthetic data generations against predefined statistical thresholds. |

| SPIRIT Guidelines [29] | Study Protocol Framework | Provides a structured framework for pre-specifying validation plans in computational studies. | Ensuring a synthetic data validation study for differential abundance methods is transparent, reproducible, and unbiased. |

| 1,2-Dichloro-2-propanol | 1,2-Dichloro-2-propanol, CAS:52515-75-0, MF:C3H6Cl2O, MW:128.98 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Potassium lauroyl glutamate | Potassium Lauroyl Glutamate | Potassium Lauroyl Glutamate is a gentle, biodegradable surfactant for research in personal care formulations. This product is for research use only (RUO). | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Machine Learning Validation Approaches

Statistical validation should be complemented with methods that test the synthetic data's functional utility in actual AI applications [12].

Discriminative Testing: This involves training a binary classifier (e.g., using XGBoost or LightGBM) to distinguish between real and synthetic samples. High-quality synthetic data should result in a classification accuracy close to 50% (random chance), indicating the model cannot reliably tell them apart [12]. Feature importance analysis from this classifier can reveal specific aspects where the generation process falls short.

Comparative Model Performance Analysis: This is considered the ultimate test for many applications. The methodology involves:

- Splitting real data into training and test sets.

- Training two identical models—one on the real training data and another on the synthetic data.

- Evaluating both models on the same real-world test set. The closer the performance of the synthetic-data-trained model is to the real-data-trained model, the higher the utility of the synthetic data [12]. This approach is invaluable for A/B testing different generation methods.

Transfer Learning Validation: This assesses whether knowledge from synthetic data transfers to real-world problems. A model is pre-trained on a large synthetic dataset and then fine-tuned on a small amount of real data. If this model significantly outperforms a baseline trained only on the limited real data, it demonstrates the high value and transferability of the synthetic patterns [12]. This is particularly powerful in medical imaging and other data-constrained domains.

For computational biology researchers and drug development professionals, robust statistical validation of synthetic data is non-negotiable. By systematically implementing the protocols for comparing distributions, correlations, and outliers, and by supplementing these with machine learning-based utility tests, scientists can build confidence in their synthetic benchmarks. This rigorous approach ensures that synthetic data will fulfill its promise as a powerful, reliable tool for accelerating discovery, validating new methods, and ultimately advancing human health, without being undermined by hidden statistical flaws.

In the data-driven fields of computational biology and drug development, synthetic data has emerged as a pivotal technology for accelerating research while navigating stringent privacy regulations and data access limitations. The core promise of synthetic data is its ability to mirror the statistical properties and complex relationships of real-world data, such as electronic health records or clinical trial data, without exposing sensitive information [31]. However, this promise hinges on a critical question: how can researchers rigorously validate that synthetic data retains the analytical utility of the original data for downstream machine learning (ML) tasks? The Train on Synthetic, Test on Real (TSTR) paradigm provides a powerful, empirical answer.

The TSTR methodology is a model-based utility test that directly measures the practical usefulness of a synthetic dataset. In this framework, a predictive model is trained exclusively on synthetic data. This model is then tested on a held-out set of real, original data that was never used in the synthetic data generation process [32]. The resulting performance metric—such as area under the curve (AUC) for a classification task—quantifies how well the knowledge captured by the synthetic data generalizes to real-world scenarios. A high TSTR score indicates that the synthetic data successfully preserves the underlying patterns and relationships of the real data, making it a valid proxy for developing and training analytical models [31]. This approach stands in contrast to the Train-Real-Test-Synthetic (TRTS) method, which is also used for complementary assessment of synthetic data quality [33].